Dorothy Creole

Dorothy Creole was one of the first black women to arrive in New York. She arrived in 1627.[1] That year, three enslaved African women set foot on the southern shore of Manhattan, arriving in the Dutch colony of New Amsterdam (Nieuw Amsterdam).[2] Property of the Dutch West India Company, these women were brought to the colony to become the wives of enslaved African men who had arrived in 1625. One of these women was named Dorothy Creole, a surname that she acquired in the New World, and likely began as a descriptive term.

Dorothy's world was one in which West Africans and Europeans had mixed and traded for more than two centuries. The Dutch had established trading posts in present-day Angola on the Slavenkust or Slave Coast to acquire slaves for their New World colonies.[3] It was also the year of the supposed sale of the island of Manhattan to the Dutch by native inhabitants for the equivalent of 24 dollars of trade goods. What is significant to Dorothy Creole's story is that by 1625, New Amsterdam was a place where Europeans, Native Americans and Blacks had significant interaction.

New Amsterdam

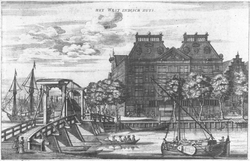

An early copper plate print of New Amsterdam shows the mix in the fledgling colony. In the foreground, a Dutch couple displays the agricultural wealth of the colony, chief among these being tobacco, very much in vogue in coffee houses of Europe. The print, circulating in Europe, was designed to attract European colonist for New Amsterdam. The Dutch West India Company wanted New Netherland to be the granary of its western Atlantic empire. Prospective colonists were attracted by the abundance of rich farm land, offering them the possibility of becoming wealthy landowners. In the middle ground of the print, figures of Black men and a woman in African garments carry goods to and fro on their heads. The brimming basket of foodstuff held by the Dutch woman is a trope for wealth and abundance. In the background, ships are shown arriving and departing from the colony with wealth from trade.

The colony was a business venture of the Dutch West India Company (WIC); and Dorothy Creole was a part of that business. The agricultural profits of the DWIC came from New World products that relied upon slave labor from Africa. The company's warehouses in Amsterdam, Europe, filled with tobacco, sugar and coffee that had been produced with slave labor from Africa and unloaded in Europe from the holds of ships returning from the New World. On Manhattan, Dorothy became a tiny link in the chain of the company business.

When Dorothy arrived in New Amsterdam, it was a hardscrabble village of thirty wooden houses clinging to the southern tip of Manhattan, today's financial capital of the world. It was also the island at the center of corporate world, linking the New World with Africa and the European continent.[4]

The DWIC had a lucrative monopoly on the Dutch North American fur trade with the Native Americans. Beaver pelts were valued for making broad-brimmed beaver hats, which were warm and water repellent, as well as expensive status symbols.

The wealthy men depicted in Rembrandt's Syndics of the Drapers' Guild are pictured with such hats that were made from beaver pelts sent to Holland from the New Amsterdam colony. The New Amsterdam fur trade, so crucial to the success of the Dutch colony, had been established by Juan (Jan) Rodriguez. Rodrigues was the first known person of African descent to arrive on Manhattan.[5] He arrived as a free man in 1613. A black sailor from Hispaniola (now Haiti and the Dominican Republic), he had set up a trading post with the native Lenape people on Manhattan.[6]

The future of the fur trade, and indeed the colony itself, was jeopardized by the actions of the DWIC Director-General, Willem Kieft. Kieft's War, (also known as the Wappinger War), was a conflict between the Dutch of the nascent colony and the local population. Lasting from 1643-1645, the conflict grew from Kieft's unauthorized order for an attack on the Lenape camps, in which the Dutch massacred native inhabitants. This action had unified the local Algonquian tribes against the Dutch, causing many attacks on both sides. Dutch settlers began to return to the Netherlands, slowing the growth of the colony.

Half-free

Part of Keift's solution was to use the African population as a buffer between the Indians and the Dutch. At the height of the fighting, Kieft opened the frontier north of New Amsterdam for settlement by Blacks. Company records show that in 1644, one Paulo d'Angola and other enslaved Africans petitioned the DWIC for their freedom, as well as the freedom of their wives. The wife of Paulo d'Angola appears to be none other than Dorothy Creole. Records of the colony show that the previous year, Dorothy had adopted a young Black child who had lost both his parents. Keift conditionally granted the petition. He conferred what was called "half-freedom," declaring them "free and at liberty on the same footing as other free people here in New Netherlands." This group of former slaves was also granted title to land in the Dutch colony. Only the names of the men appear in the records. Some historians feel that half-freedom for the petitioners' wives came only when these men paid for the women's half-freedom.

These families received the right to own land north of the settlement to farm and settle. Called the "Land of the Blacks" or the "Negro Frontier," this two-mile stretch from Canal Street to today's 34th Street was established as one of the first free Black communities in North America, clearly outside the boundaries of the colony.[7]

Half-freedom was given by the DWIC with many conditions. Men and women who were half-free paid an annual tax of "30 skepels (around 3/4 bushel) of maize, wheat, peas or beans and one fat hog.” Further, half-free residents of the Dutch colony had to work for the settlement when required. This work might include, for example, building the palisade at Wall Street built in 1653 to defend the colony from the native inhabitants. It was a permeable barrier built to protect the colony while allowing the passage of valuable goods to enter the city. Blacks thus often found themselves interacting between the Dutch and the native inhabitants.

Half-free men were required to serve in the colony's militia. It is true that there conditions and contributions were often required by the city's free, white population. However, offspring of half-free residents did not enjoy the same status as their parents. They remained slaves of the DWIC, binding them in perpetuity to the company.

The land grant received by Dorothy Creole and Paulo d’Angola from eight to twelve acres, a sizable piece of property that would confer their status as among the largest black landowners in the entire history of New York City to this day. This property would allow the couple to raise crops for sale and taxes. They would have also had a kitchen garden for their own use and pastureland for animals. Many Dutch resident planted orchards, and Dorothy and Paulo likely planted apple, peach, plum and cherry trees. The couple built their house themselves, using wood and thatch from resources on Manhattan island using the same materials as the Dutch citizens living in the city proper, south of the palisade at Wall Street.

The Journal of Jasper Danckaerts (1679-1680)[8] describes this area and its inhabitants:

These negroes were formerly the proper slaves of the (West India) company, but, in consequence of the frequent changes and conquests of the country, they have obtained their freedom and settled themselves down where they have thought proper, and thus on this road, where they have ground enough to live on with their families.

The road formerly called the Negroes' Causeway connected several farms in the Land of the Blacks with the settlement located south of the palisade at Wall Street. It is located in today's Greenwich Village. Minetta Lane is all that remains of a road that once ran alongside Minetta Creek.

DWIC records have no mention of either Dorothy or Paulo until 1653. In that year, one Dorothy d’Angola, then a widow, marries Emanuel Pietersen. Missing also is information on her adopted child or land and property that survived her demise. There is no record of her place of burial. But we can contextualize Dorothy Creole's life and legacy in the history of the colony of New Amsterdam to try and fill in information where lacunae exist.

The DWIC did not approve of Willem Kieft’s rule as director-general of New Amsterdam. His conflict with local native groups was bad for the fur trade, which was the primary economic motor of the colony. Called back to the Netherlands in disgrace, Kieft died in a shipwreck during his return journey. His replacement, was Pieter Stuyvesant, a seasoned administrator and soldier, who was counted upon to renew the failing Dutch colony.

In 1664, Stuyvesant surrendered the colony to the British without firing a shot. New Amsterdam became New York, named for James II, the Duke of York, later both James II and VII.

The Duke of York was a principle investor in the Company of Royal Adventures Trading To Africa. Association with a name that boded ill for the future of blacks in the colony. Under the British, life for black New Yorkers, enslaved and free, changed dramatically. Laws passed by the British following the 1712 Slave Uprising, prohibited freed African New Yorkers from owning real estate. They were forced to forfeit their property to the British crown. Likely, the farm established by Dorothy and Paulo was lost in this way.

_van_het_Amsterdamse_lakenbereidersgilde_-_Google_Art_Project.jpg)

References

- New-York Historical Society. "New-York Historical Society New-York Stories" (PDF).

- Wk (2007-08-18). "New York Slavery: Chapter Two". New York Slavery. Retrieved 2018-12-06.

- "Nederlands Elmina: een socio-economische analyse van de Tweede Westindische Compagnie in West-Afrika in 1715. (Yves Delepeleire)". www.ethesis.net. Retrieved 2018-12-06.

- Shorto, Russell. "Island at the Center of the World". www.amazon.com. Retrieved 2018-12-06.

- "El primer habitante de Nueva York era latino". BBC News Mundo (in Spanish). Retrieved 2018-12-06.

- "The City College of New York". www.ccny.cuny.edu. Retrieved 2018-12-06.

- "MAAP | Place Detail: Land of the Blacks". maap.columbia.edu. Retrieved 2018-12-07.

- Danckaerts, Jasper (1913). Journal of Jasper Danckaerts, 1679-1680. Smithsonian Institution: C. Scribner's Sons. pp. ?.