Dorchester House

Dorchester House was a mansion in Park Lane, London, built in 1853 by Robert Stayner Holford. It was demolished in 1929 to make way for the present Dorchester Hotel.

Overview

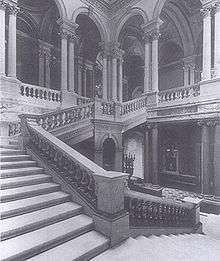

Lewis Vulliamy, who was a notable architect of that time, was instructed to build a house in which a central staircase was a major feature.[1] The main purpose of the building was to house the extensive collection of paintings that Holford had acquired over many years and at that time were temporarily lodged in a friend's residence in Russell Square.[2] Vulliamy's assistant in this project was Jacob Wrey Mould. The 19th-century architecture critic Clarence Cook attributes the grand staircase specifically to Mould, who undertook that task while Vulliamy was incapacitated.[3] Mould subsequently went on to work with Calvert Vaux on many of the initial buildings and design details of New York's Central Park, very notably, Bethesda Terrace.[3]

A description of the house was provided by a publication of that time.

- "(the staircase) occupies the centre of the house and is lighted from above, and from the gallery round it open that remarkable range of apartments – the Saloon, the Green Drawing Room, the Red Drawing Room, and the State Drawing Room – in which the ceilings and other decorations are from the hands of Italian artists and the beautiful chimney-pieces are by Alfred Stevens, and probably represent the finest work that great artist ever achieved. In these rooms hang some of the notable pictures of the great masters, Titian and Tintoretto, Velasquet and Vandyck and Murillo, Rembrandt and Claude and Cuypt and Ruysdael."[4]

The grand central staircase

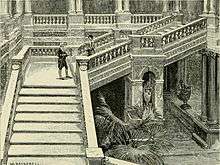

Dorchester House was one of the more palatial buildings in London at the turn of the twentieth century and was frequently mentioned in publications of the time. The staircase (see picture at right) was a notable feature that received much praise. Guy Cadogan Rothery in his book Staircases and Garden Steps said.

- "The staircase itself is of marble and the steps having broad treads, moderate nosings and very low risers. A flight runs parallel to one side of the gallery to the angle of the wall where there is a landing, and then another flight parallel to the other side to the first floor, with an intermediate landing supported on small open arches. The balustrade is of marble with a broad flat handrail and dwarf pillars with swelling bases"[5]

The Magazine of Art described it in the following terms.

- "This staircase is one of the most beautiful and interesting portions of house, I shall describe more minutely below. It is noticeable now, as giving a key to the external appearance of the whole. Round three sides of it on the east, south and west the principal rooms are grouped; and the simplicity of the arrangement has enabled the architect to obtain an external effect of considerable grace and dignity."[1]

The magazine illustrated its description of the staircase with a very detailed drawing (see picture left).

The chimneypiece by Alfred George Stevens

One of the most celebrated inclusions in Dorchester House was the chimneypiece in the dining room sculptured by Alfred Stevens (see picture at right). It was regarded as one of his finest works. The Magazine of Art in 1883 contained the following comment.

- "Here Stevens sought after a massive breadth of effect. There is something of grandeur and repose in the two figures which reminds you in some degree of the work of Michelangelo. It is of no use stopping to inquire whether such a use of the human figure is legitimate. In this particular case the answer comes at once – that it has succeeded"[6]

Rothery made similar laudatory expressions.

- "In his Dorchester House chimneypiece he has two figures, who are in a crouching position on each side. They belong to the design yet are doing very little absolute work. Possibly here the wonderful sense of harmony is gained by the splendid modelling of practically nude forms, with their evidence of vigour and great dormant strength. In this way too he has managed to utilise the undraped figure without any incongruity for so conspicuous a position in a room for general assembly."[7]

The two figures referred to are shown below.

Even though Stevens was credited with the work, he did not complete it before his death in 1875. The picture below, taken by the Magazine "British Architect" shortly after Stevens' death, shows the incomplete chimneypiece. The Victoria and Albert Museum now have the chimneypiece (picture shown below), and according to them it was finished later by Steven's former pupil, James Gamble.[8]

Left Caryatid in the chimneypiece by Alfred Stevens 1908.

Left Caryatid in the chimneypiece by Alfred Stevens 1908. Right Caryatid in the chimneypiece by Alfred Stevens 1908.

Right Caryatid in the chimneypiece by Alfred Stevens 1908. The unfinished chimneypiece of Alfred Stevens. Photo taken shortly after his death in 1875

The unfinished chimneypiece of Alfred Stevens. Photo taken shortly after his death in 1875 The chimneypiece by Alfred Stevens now in the Gamble Room of the Victoria and Albert Museum, London

The chimneypiece by Alfred Stevens now in the Gamble Room of the Victoria and Albert Museum, London

Other rooms in Dorchester House

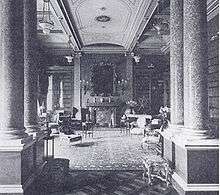

The library was an important room of the house and was specially designed to house Holford's large book collection (see picture right). Morris describes it in the following terms.

- "The library emerged as a magnificent and functional reflection of the superb quality of the books....The walls were covered in green silk damask and the floor with a buff and green Axminster carpet. The glass-enclosed bookcases were of carved and gilded walnut made by Holland and Sons, each center compartment being 13.6 feet high and 8 feet wide."[9]

Three other rooms in the house were designed to accommodate Holford's famous art collection. The Grand Saloon (see picture below, left) was frequently mentioned in period publications. It was described by one as "a well-proportioned room. The walls covered with red damask and devoted to pictures. The ceiling a good piece of work of its kind was designed by Mr G. E Fox and executed by Mr Alfred Morgan."[10] The other two rooms. known as the green and red drawing rooms (see pictures below), were described by the same author as follows.

- "The green and red drawing-rooms follow in succession from the saloon. The ceilings of both were painted by Signor Anglinatti while the frieze of the latter is a bright bit of work by Sir Coutts Lindsay... The furniture of these drawing-rooms is well worth notice. Every piece is good of its kind and is thoroughly adapted to the style of its surroundings and its individual place."[11]

|

|

|

| The grand saloon of Dorchester House | The green drawing room of Dorchester House |

The red drawing room of Dorchester House showing the frieze by Sir Coutts Lindsay |

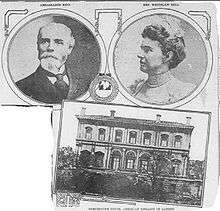

Dorchester House as the American Embassy

Robert Holford died in 1892 and his son, Sir George Holford, inherited Dorchester House. George did not often occupy the house so in 1905 he rented it to Whitelaw Reid, the American Ambassador. Reid held lavish functions as part of his duties, many of which were mentioned in the newspapers. Of particular note were the Fourth of July celebrations. The New York Times gave the following details of this function held by the Reids at Dorchester House in 1907.

- "So many Americans attended Ambassador Reid's Fourth of July reception this afternoon that traffic in several squares about Dorchester House was blocked for two hours. Mr Reid and the ladies of the embassy received the guests. Although admittance was by invitation and only Americans, with a few exceptions, were asked to call, the crush was as great as at a White House reception.

- A long buffet tent was erected on the north terrace, access to which was obtained by the removal of some windows and the erection of temporary staircases carpeted with crimson cloth. Nearly 4,000 invitations were issued."[12]

In the same year Reid hosted a function for Mark Twain. The Chancellor of Oxford University wished to confer an honorary degree of Doctor of Letters upon Twain and asked Reid to convey this invitation. Twain accepted and a few days before the Oxford ceremony a dinner was held at Dorchester House for him. Reid invited about forty authors and artists to meet Twain, one of whom was Sir Arthur Conan Doyle.[13]

In 1908 the Reids' daughter Jean was married and the reception was held at Dorchester House. The wedding received a great deal of publicity because King Edward and Queen Alexandra attended. One newspaper commented.

- King Edward was profuse in his congratulations to the bride and the bridegroom and their families. With Queen Alexandra, the Prince and Princess of Wales and the Duke of Connaught (Incomplete sentence). His majesty remained at Dorchester House for some time mingling freely with the guests of the American Ambassador.[14]

Another newspaper said.

- The marriage of Miss Jean Reid, daughter of Whitelaw Reid, American Ambassador to Great Britain, to the Hon. John Hubert Ward took place at the Church Chapel Royal, St James's Palace, this afternoon. Not since the Prince of Wales was married has a wedding ceremony taken place in circumstances of such pomp and majesty. After the wedding a reception was held at Dorchester House, to which all fashionable London and many Americans who could not be accommodated at the chapel were invited.[15]

In 1910 after the death of King Edward VII, former President Theodore Roosevelt came to London to attend the funeral. He stayed at Dorchester House for three weeks.[16] The New York Times outlines the numerous visits from dignitaries from other countries that came to Dorchester house to see Roosevelt during this time.

- "The Roosevelts had just returned to Dorchester House when they received a return call from King Haakon who greeted the Special Ambassador and his wife as old friends. While luncheon was being served the Duke of Connaught and Prince Arthur of Connaught called...The diplomatic representatives of all the powers called at Dorchester House in the course of the day and left cards for Mr. Roosevelt."[17]

In 1912 Whitelaw Reid died and Dorchester House was no longer used as the American Embassy. Holford used it for occasional parties and to house his orchid collection.

Dorchester House as a hospital during World War I

During World War I many of the stately homes of England became Auxiliary Home Hospitals[18] Dorchester House was also offered as a hospital by George Holford. The New York Times in 1914 contained a story about the House as a hospital.

- "Lieutenant Colonel Sir George Holford, the owner of the house has given it up to wounded officers eighteen of whom are billeted in bedrooms overlooking Hyde Park. Downstairs on the first floor the famous ballroom is being turned into a sitting room for convalescents, and other splendid apartments in which dinners and receptions were held are now filled with beds, screens and big medicine tables and will become dormitories...The famous Velasquez and other masterpieces at Dorchester House have been taken down to a cellar, but the Alfred Stevens decorations are still in place"[19]

Demolition of Dorchester House

In 1926 Sir George Holford died. His heir was Edmund Parker, 4th Earl of Morley (1877–1951), whose mother was Margaret Holford (1855–1908), daughter of Robert Stayner Holford. The Earl was at that time in a very poor financial condition, having inherited large debts from his father and grandfather, and immediately put up for sale his Holford inheritance of both Dorchester House and Westonbirt House in Gloucestershire, although he retained the arboretum of the latter.[20] After three years an acceptable offer was received and Dorchester House was sold. The following article was published in The Times on 16 July 1929:

- "Lord Morley has sold Dorchester House, Park Lane. A contract was signed yesterday afternoon for the purchase of the property by Gordon Hotels, Limited, associated in the transaction of purchase being Sir Robert McAlpine and Sons, Limited. The famous mansion will be demolished and the Gordon Hotels Limited intend to proceed at once with the erection of an hotel."[21]

Dorchester House was duly demolished in 1929 and the new Dorchester Hotel opened in 1931.

Notes

- Balfour 1883, p. 398.

- Chancellor 1908, p. 251.

- Cook, C. 1869. A Description of the New York Central Park. New York: Huntington. pp. 50–51.

- Chancellor 1908, p. 252.

- Rothery, 1912, p. 179.

- Balfour 1883, p. 404.

- Rothery 1911, p. 79.

- "Caryatid". Victoria and Albert Museum. Retrieved 2 January 2010.

- Morris 1988, p. 15.

- Balfour 1883, p. 403.

- Balfour 1883, pp. 403–4.

- "Fourth Celebrated in Foreign Cities" (PDF). The New York Times. 5 July 1907. Retrieved 7 January 2010.

- Cortissoz 1921, p. 381.

- "The Evening World" 23 June 1908, p. 3.

- "Alexandria Gazette" 23 June 1908.

- Cortissoz 1921, p. 416.

- "Great Crowd at the Palace" (PDF). The New York Times. 17 May 1910. Retrieved 7 January 2010.

- "Roll of Auxiliary Home Hospitals in the United Kingdom 1914–1919". Kent VAD. Archived from the original on 2 February 2010. Retrieved 7 January 2010.

- "Famous House a Hospital" (PDF). The New York Times. 14 November 1914. Retrieved 7 January 2010.

- Johnson, Ceri, Saltram House, Devon, guidebook, 2005, pp.54–57

- "The Times", 16 July 1929 p. 16

References

- Chancellor, Edwin Beresford (1908). The private Palaces of London: Past and Present. London: Kegan Paul, Trench, Trubner and Co. Ltd. OCLC 187097754.

- Balfour, Eustace (January 1883). "Dorchester House". Magazine of Art. London: Cassell, Petter & Galpin. 6. OCLC 145082443.

- Morris, Leslie A. (1988). Rosenbach Abroad: In pursuit of Books in Private Collections. Philadelphia: Rosenbach Museum and Library. ISBN 978-0-939084-22-7.

- Cortissoz, Royal (1921). The Life of Whitelaw Reid. 2. New York: C. Scribner's Sons. OCLC 186402.

- Rothery, Guy Cadogan (2008) [1912]. Staircases and Garden Steps. London: T. Werner Laurie. ISBN 978-1-4437-8314-9.

- Rothery, Guy Cadogan (1911). Chimneypieces and Ingle Nooks: Their Design and Ornamentation. New York: Stokes. OCLC 8837935.