Doodle

A doodle is a drawing made while a person's attention is otherwise occupied. Doodles are simple drawings that can have concrete representational meaning or may just be composed of random and abstract lines, generally without ever lifting the drawing device from the paper, in which case it is usually called a "scribble".

Doodling and scribbling are most often associated with young children and toddlers, because their lack of hand–eye coordination and lower mental development often make it very difficult for any young child to keep their coloring attempts within the line art of the subject. Despite this, it is not uncommon to see such behavior with adults, in which case it is generally done jovially, out of boredom.

Typical examples of doodling are found in school notebooks, often in the margins, drawn by students daydreaming or losing interest during class.[1] Other common examples of doodling are produced during long telephone conversations if a pen and paper are available.

Popular kinds of doodles include cartoon versions of teachers or companions in a school, famous TV or comic characters, invented fictional beings, landscapes, geometric shapes, patterns, textures, or phallic scenes. Most people who doodle often remake the same shape or type of doodle throughout their lifetime.[2]

Etymology

The word doodle first appeared in the early 17th century to mean a fool or simpleton.[3] It may derive from the German Dudeltopf or Dudeldop, meaning simpleton or noodle (literally "nightcap").[3] It is the origin of the early eighteenth century verb to doodle, meaning "to swindle or to make a fool of". The modern meaning emerged as a term for a politician who was doing nothing in office at the expense of his constituents.[4] That led to the more generalized verb "to doodle", which means to do nothing.[4]

In the final courtroom scene of the 1936 film Mr. Deeds Goes to Town, the main character explains the concept of "doodling" to a judge unfamiliar with the word, saying that "People draw the most idiotic pictures when they're thinking."[5][6][7] The character, who has travelled from a fictional town in Vermont, describes the word doodler as being "a name we made up back home" for people who make "foolish designs" on paper when their mind is on something else.[7]

The meaning "fool, simpleton" is intended in the song title "Yankee Doodle", originally sung by British colonial troops during the American Revolutionary War.[8]

Effects on memory

According to a study published in the scientific journal Applied Cognitive Psychology, doodling can aid a person's memory by expending just enough energy to keep one from daydreaming, which demands a lot of the brain's processing power, as well as from not paying attention. Thus, it acts as a mediator between the spectrum of thinking too much or thinking too little and helps focus on the current situation. The study was done by Professor Jackie Andrade, of the School of Psychology at the University of Plymouth, who reported that doodlers in her experiment recalled 7.5 pieces of information (out of 16 total) on average, 29% more than the average of 5.8 recalled by the control group made of non-doodlers.[9]

Doodling has positive effects on human comprehension as well. Creating visual depictions of information allows for a deeper understanding of material being learned.[10] When doodling, a person is engaging neurological pathways in ways that allow for effective and efficient sifting and processing of information.[4] For these reasons, doodling is used as an effective study tool and memory device.

As a therapeutic device

Doodling can be used as a stress relieving technique. This is similar to other motor activities such as fidgeting or pacing that are also used to alleviate mental stress. According to a review of over 9,000 submitted doodles, nearly 2/3 of respondents recalled doodling when in a "tense or restless state" as a means to reduce those feelings. [11] Scientists believe that doodling's stress relieving properties arise from the way that the act of doodling engages with the brain's default mode network.[2] Doodling is often incorporated into art therapy, allowing its users to slow down, focus and de-stress.[12]

Notable doodlers

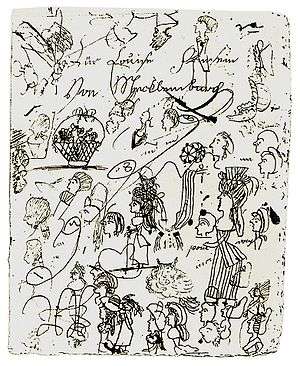

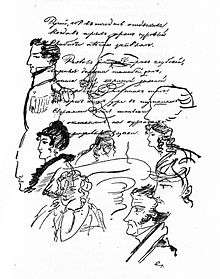

Alexander Pushkin's notebooks are celebrated for their superabundance of marginal doodles, which include sketches of friends' profiles, hands, and feet. These notebooks are regarded as a work of art in their own right. Full editions of Pushkin's doodles have been undertaken on several occasions.[13] Some of Pushkin's doodles were animated by Andrei Khrzhanovsky and Yuriy Norshteyn in the 1987 film My Favorite Time.[14][15]

Other notable literary doodlers have included: Samuel Beckett;[16] the poet and physician John Keats, who doodled in the margins of his medical notes; Sylvia Plath;[16] and the Nobel laureate (in literature, 1913) poet Rabindranath Tagore, who made numerous doodles in his manuscript.[17]

Mathematician Stanislaw Ulam developed the Ulam spiral for visualization of prime numbers while doodling during a boring presentation at a mathematics conference.[18]

Many American Presidents, including Thomas Jefferson, Ronald Reagan, and Bill Clinton, have been known to doodle during meetings.[19]

Some doodles and drawings can be found in notebooks of Leonardo da Vinci.[20]

See also

- Asemic writing

- Automatic writing

- Drolleries

- Fidgeting

- Graffiti

- Graphology

- Marginalia

- Memory and retention in learning

- Recall (memory)

- Stick figure

- Stream of consciousness writing

- Ulam spiral

References

- Archey, Karen (2013). Hymns for Mr. Suzuki. Abrons Art Center.

Further meditating on the stereotype of female irrationality are [Cindy] Hinant’s untitled heart drawings, recalling grade school doodles made by obsessive girls killing class time by channeling her newest beau.

- Schott, G. D. (2011-09-24). "Doodling and the default network of the brain". The Lancet. 378 (9797): 1133–1134. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(11)61496-7. ISSN 0140-6736. PMID 21969958.

- "Doodle (noun)". Oxford English Dictionary.

- Brown, Sunni (2014). The Doodle Revolution. New York: Portfolio/Penguin. p. 11. ISBN 978-1-59184-703-8.

- "Doodle (verb)". Etymonline. Retrieved 11 March 2017.

- "Doodle". Dictionary.com. Retrieved 11 March 2017.

- Riskin, Robert (1997). Six Screenplays. University of California Press. p. 456. ISBN 978-0-520-20525-3. Retrieved 11 March 2017.

- Roberts, Chris (2005). Heavy Words Lightly Thrown. New York: Gotham Books. pp. 87–91. ISBN 1-592-40130-9.

- Andrade, Jackie (January 2010). "What does doodling do?". Applied Cognitive Psychology. 24 (1): 100–106. doi:10.1002/acp.1561. hdl:10026.1/4701.

- Ainsworth, S.; Prain, V.; Tytler, R. (2011-08-26). "Drawing to Learn in Science" (PDF). Science. 333 (6046): 1096–1097. doi:10.1126/science.1204153. ISSN 0036-8075. PMID 21868658.

- Maclay, W. S.; Guttmann, E.; Mayer-Gross, W. (April 12, 1938). "Spontaneous Drawings as an Approach to some Problems of Psychopathology: (Section of Psychiatry)". Proceedings of the Royal Society of Medicine. 31 (11): 1337–1350. doi:10.1177/003591573803101113. ISSN 0035-9157. PMC 2076785. PMID 19991673.

- "Doodling Your Way to a More Mindful Life". Psychology Today. Retrieved 2019-10-16.

- "Pushkin Drawings". feb-web.ru (in Russian). Archived from the original on 2014-09-08.

- Sandler, Stephanie (2004). Commemorating Pushkin: Russia's Myth of a National Poet. Stanford University Press. p. 156. ISBN 978-0-8047-3448-6. Retrieved 11 March 2017.

- Bethea, David M. (19 December 2013). The Pushkin Handbook. University of Wisconsin Pres. pp. 412–414. ISBN 978-0-299-19563-2. Retrieved 11 March 2017.

- Temple, Emily (January 30, 2011). "Idle Doodles by Famous Authors". Flavorwire. Retrieved 11 March 2017.

- Banerjee, Nilanjan (2011). Wings of Mistakes: Doodles of Rabindranath Tagore. Kolkata: Punascha in association with Visva-Bharati.

- Gardner 1964, p. 122.

- "All the Presidents' Doodles". The Atlantic. Retrieved 2012-05-02.

- Weber, Joel (October 18, 2017). "What Leonardo da Vinci and Steve Jobs Have in Common". Bloomberg. Retrieved 16 October 2019.

| Look up doodle or scribble in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Doodles. |

Further references

- Doodle (drawing) at the Encyclopædia Britannica

- Brown, Sunni. "Doodlers, unite!". ted.com. Retrieved September 23, 2011.

- "Doodling As A Creative Process". Enchantedmind.com. Retrieved June 10, 2011.

- Gardner, M. (March 1964). "Mathematical Games: The Remarkable Lore of the Prime Number". Scientific American. 210: 120–128. doi:10.1038/scientificamerican0364-120.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Gombrich, E. H. (1999). "Pleasures of Boredom: Four Centuries of Doodles". The Uses of Images. London: Phaidon. pp. 212–225.

- Hanusiak, Xenia (October 6, 2009). "The lost art of doodling". Smh.com.au. Retrieved June 10, 2011.

- Malchiodi, Cathy (January 13, 2014). "Doodling Your Way to a More Mindful Life". Psychology Today. Retrieved March 15, 2015.

- Spiegel, Alix (March 12, 2009). "Bored? Try Doodling To Keep The Brain On Task". NPR.org. Retrieved June 10, 2011.