Don Checco

Don Checco is an opera in two acts composed by Nicola De Giosa to a libretto by Almerindo Spadetta. It premiered on 11 July 1850 at the Teatro Nuovo in Naples. Don Checco was De Giosa's masterpiece and one of the last great successes in the history of Neapolitan opera buffa.[1][2]

| Don Checco | |

|---|---|

| Opera by Nicola De Giosa | |

Don Checco Cerifoglio, the opera's protagonist | |

| Librettist | Almerindo Spadetta |

| Language | Italian |

| Premiere | |

Set in a village inn near Naples, the opera's story has the usual elements of the Neapolitan opera buffa genre—young lovers in difficulty, deceptions, mistaken identities, and a happy ending. Its protagonist and a guest at the inn is Don Checco Cerifoglio, an elderly gentleman deep in debt and fleeing the bailiff of the mysterious Count de Ridolfi. The opera had an initial run of 98 performances at the Teatro Nuovo and was regularly produced in numerous opera houses in Italy and abroad over the next four decades. After years of neglect, it was revived in 2014 in a co-production by the Teatro San Carlo in Naples and the Festival della Valle d'Itria in Martina Franca.

Background

Don Checco was De Giosa's fifth opera. Almerindo Spadetta, a lawyer by training and prolific librettist by vocation, had also written the libretto for De Giosa's second opera Elvina, an opera semiseria which premiered in Naples in 1845. In Don Checco, as in most Neapolitan opere buffe of the period, the lead characters' spoken dialogue and arias were in Neapolitan dialect. The success or failure of the work often depended on the skill of the basso buffo singing the lead who would improvise many of his lines, sometimes addressing the audience directly. De Giosa's Don Checco was Raffaele Casaccia, a veteran of Neapolitan opera houses famed for his comic interpretations. Two of the other key basso buffo roles, Bartolaccio and Succhiello (Don Checco's main antagonists), were taken by Giuseppe Fioravanti and his son Valentino. Like Casaccia, they were both staples on the roster of the Teatro Nuovo in Naples. Music historian Sebastian Werr has pointed out that the impoverished Don Checco, who initially obtains free room and board at the inn through deception but ultimately has his debts forgiven, can be seen as fulfilling a fantasy of the Teatro Nuovo's audiences. They were mostly from the Neapolitan middle and lower-middle classes and barely scraping a living themselves. According to Werr, the finale, Don Checco's paean to indebtedness, is also an affirmation of the notion, "often seen as characteristically Neapolitan, that a certain brazenness is necessary to getting by in life."[3][4]

Performance history

The premiere of Don Checco on 11 July 1850 at the Teatro Nuovo was a resounding success. It had an initial run of 98 performances, and in 1851 the Teatro Nuovo's production with its singers and orchestra were imported to the "Royal Opera House" of Naples, the Teatro San Carlo, for a special performance to benefit the city's poor. According to contemporary accounts it raised a vast sum of money. The opera was a particular favourite of King Ferdinand II who often attended its performances in Naples.[5] On a state visit to Lecce in 1859, the city had prepared a gala performance of Verdi's Il trovatore for him. However, when Ferdinand heard the plans and found out that Michele Mazzara, a famous Neapolitan basso buffo, was in town, he demanded that his hosts put on Don Checco instead: "Trovatore and Trovatore, I want to hear Don Checco. I want to have fun."[lower-alpha 1] The theatre duly organized the performance on a few hours notice.[6][7]

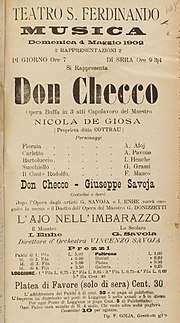

In the four decades after its premiere Don Checco would have over 80 different productions. It was performed throughout Italy and abroad, including France, Malta, Cairo, Barcelona[lower-alpha 2] and Madrid[lower-alpha 3], and was still being performed in Naples as late as 1902. For performances outside Naples, the libretto was usually adapted for local tastes, with Don Checco's lines translated from Neapolitan into Italian. The adaptations included Carlo Cambaggio's Italian version of the libretto which converted Spadetta's original prose into verse. Another version of the libretto published in 1877 adapted the story for an all-male cast with the innkeeper's daughter Fiorina (the sole female character in the original version) becoming the innkeeper's son Fiorino.[3] Despite its great popularity, Don Checco had fallen from the repertoire by the early 20th century, although it was later evoked in "Don Checchino", a bravura patter song composed by Raffaele Viviani for performance in his 1933 play L'ombra di Pulcinella.[lower-alpha 4][5][11]

The opera's first performance in modern times took place on 25 September 2014 in the court theatre of the Royal Palace of Naples, the former home of Ferdinand II. The revival was a co-production by the Teatro San Carlo in Naples and the Festival della Valle d'Itria in Martina Franca. It was performed using a critical edition of the score by Lorenzo Fico and was directed by Lorenzo Amato who updated the time setting from 1800 to the 1950s. Francesco Lanzillotta conducted the Teatro San Carlo orchestra and chorus. The opera was performed again in July 2015 at the Festival della Valle d'Itria. The performance there (with a new cast) was recorded live and released in 2016 on the Dynamic label.[12][13][14]

Roles

| Role | Voice type | Premiere cast, 11 July 1850[15] |

|---|---|---|

| Don Checco Cerifoglio, an elderly gentleman fallen on hard times | bass | Raffaele Casaccia |

| Bartolaccio, an innkeeper | bass | Giuseppe Fioravanti |

| Fiorina, Bartolaccio's daughter | soprano | Giorgina Evrard |

| Carletto, Bartolaccio's head waiter | tenor | Tancredi Remorini |

| Roberto, a painter, actually Count de Ridolfi in disguise | bass | Raffaele Grandillo |

| Succhiello Scorticone, Count de Ridolfi's bailiff | bass | Valentino Fioravanti |

| Peasants, customers of the inn, police officers, waiters, a farmer | ||

Synopsis

Setting: A village near Naples in the early 19th century[16]

Act 1

The opera opens inside Bartolaccio's inn. The road to Naples with hills in the distance can be seen through the inn's entrance. Bartolaccio's daughter Fiorina is at her spinning wheel in the dining room, while Bartolaccio and his head waiter Carletto scurry about serving the guests. Roberto, an artist staying at the inn, sits to one side of the room painting at his easel and seemingly uninterested in the goings-on. Unbeknownst to all, he is really the wealthy Count de Ridolfi in disguise. Bartolaccio accuses Fiorina of flirting with all the men present and orders her to take her spinning wheel into the kitchen. Roberto remonstrates with him for his harsh behaviour as does Fiorina. Later Fiorina and Carletto declare their love for each other. When they tell Bartolaccio, he adamantly refuses to consent to the marriage, vowing he will only allow Fiorina to marry a wealthy man. He orders Carletto out of the inn, but the young man manages to sneak into the cellar instead.

At this point Don Checco Cerifoglio bursts into the inn. Poorly dressed and completely frazzled, he is on the run from a bailiff pursuing him for the many debts he owes to Count de Ridolfi. During a lengthy exchange between Don Checco and Bartolaccio who comes to take his dinner order, Bartolaccio becomes convinced that Don Checco is really Count de Ridolfi. The count is known to travel around his dominion in disguise to observe his subjects. Since Bartolaccio also owes money to the count, he treats his guest obsequiously. Don Checco allows Bartolaccio to believe he is the count, while Roberto (the real count) looks on with bemusement at this turn of events. Later Fiorina and Carletto approach Don Checco. They too are convinced that he is the count and hope he will intercede with Bartolaccio on their behalf. Fiorina begins to tell her story, but Don Checco misunderstands her and thinks she is in love with him. When she and Carletto disabuse him of this, he flies into a rage. Fiorina runs into the kitchen, and Carletto once again seeks refuge in the cellar.

Act 2

Fiorina and Carletto again approach Don Checco. They ask his forgiveness for the previous misunderstanding, and he grudgingly concedes to intervene on their behalf. After they leave, Roberto, who has heard the entire exchange from his room, also urges Don Checco to help the young couple. While waiting for his meal, Don Checco hears someone hissing at him from the entrance. It is Succhiello Scorticone, the bailiff who has been pursuing him. He orders Don Checco to come outside so he can be arrested. Don Checco refuses, and an angry exchange takes place. At this point Bartolaccio arrives. Having talked to Succhiello, he is furious that Don Checco has made a fool of him and orders him to leave. Don Checco again refuses.

Fiorina and Carletto are waiting at the inn for the arrival of the notary who will marry them. Still believing that Don Checco is really Count de Ridolfi, the young couple are convinced that he has interceded with Fiorina's father to allow the marriage. As a powerful nobleman, he would not be refused. Meanwhile, peasants who had heard that the count was staying at the inn arrive bearing flowers and wreathes to pay homage to him. Surrounded by the peasants and with the bailiff and two policeman waiting outside, Don Checco becomes desperate. Things become worse for him with the arrival of Bartolaccio who exposes Don Checco's deception to the consternation of everyone.

A peasant then hands a letter to Succhiello who opens it and reads the contents to all present. It is from Count de Ridolfi. In it he forgives the debts of both Don Checco and Bartolaccio and states his express wish that Fiorina and Carletto be married. He also bestows a dowry of 1000 ducats on Fiorina and a gift of 3000 ducats on Carletto. Astounded, Bartolaccio asks Succhiello how the count could have possibly known what was going on at the inn. Succhiello reveals that the count had been there all along disguised as the artist Roberto. Bartolaccio happily consents to the marriage and offers Don Checco free hospitality at his inn. The opera ends with Don Checco singing a lengthy soliloquy on indebtedness and noting that it can sometimes lead to unforeseen happiness. He then bids farewell to all, "Remember me, Don Checco the debtor", to which they reply, "Yes, everyone will remember the lucky debtor." The curtain falls.

Recording

- De Giosa: Don Checco – Domenico Colaianni (Don Checco), Carmine Monaco (Bartolaccio), Carolina Lippo (Fiorina), Francesco Castoro (Carletto), Rocco Cavalluzzi (Roberto), Paolo Cauteruccio (Succhiello Scorticone); Transylvania State Philharmonic Chorus, Orchestra Internazionale d’Italia, Matteo Beltrami (conductor). Recorded live at the Festival della Valle d'Itria, July 2015. Label: Dynamic CDS7737[17]

Notes

- Original Italian: "Che Trovatore e Trovatore, voglio sentì Don Checco; me voglio divertì"[6]

- In Barcelona the opera was presented under the title Don Paco. A printed libretto from 1859 is partly in Spanish and partly in Italian.[8]

- In Madrid the opera was presented as a zarzuela translated by Carlos Frontaura under the title De incógnito [9] (Teatro del Circo, 1861). [10]

- "Checchino" is the diminutive of "Checco".[11]

References

- Antolini, Bianca Maria (1988). "De Giosa, Nicola". Dizionario Biografico degli Italiani, Vol. 36. Treccani. Online version retrieved 27 June 2017 (in Italian).

- Lanza, Andrea (2001). "De Giosa, Nicola". Grove Music Online. Retrieved 27 June 2017 (subscription required for full access).

- Werr, Sebastian (November 2002). "Neapolitan elements and comedy in nineteenth-century opera buffa". Cambridge Opera Journal, Vol. 14, No. 3, pp. 297–311. Retrieved 7 July 2017 (subscription required).

- Ascarelli, Alessandra (1978). "Casaccia". Dizionario Biografico degli Italiani, Vol. 21. Online version retrieved 7 July 2017 (in Italian).

- Pennisi, Giuseppe (2014). "I gioielli dell'opera buffa napoletana". Musica. Retrieved 7 July 2017 (in Italian).

- De Cesare, Raffaele (1900). La fine di un regno, p. 380. S. Lapi (in Italian)

- "Acuto" (pseudonym of Federico Polidoro) (11 October 1885). "Nicola De Giosa". Gazzetta musicale di Milano, pp. 345–346 (in Italian)

- Spadetta, Almerindo (1859). Don Paco: opera bufa en dos actos. Tomás Gorchs

- Frontaura, Carlos (1861). De incógnito. Imprenta de Manuel Galiano (libretto printed for the premiere run)

- Cotarelo y Mori, Emilio (1934). Historia de la zarzuela, o sea el drama lírico en España desde su origen a fines del siglo XIX. Tipografía de Archivos, p. 771 (facsimile edition: Instituto Complutense de Ciencias Musicales, 2000) (in Spanish) ISBN 8489457204

- Viviani, Raffaele (edited and annotated by Pasquale Scialò) (2006). Canti di scena, p. 65. Guida ISBN 886042982X

- Fabris, Dinko (September 2015). "Il ritorno di Don Checco". Giornale della Musica. Retrieved 7 July 2017 (in Italian).

- Chierici, Luca (August 2015). "«Don Checco» a Martina Franca". Il Corriere Musicale. Retrieved 7 July 2017 (in Italian).

- Opera News (October 2016). "Recording Reviews: De Giosa: Don Checco". Retrieved 7 July 2017 (subscription required).

- Università degli Studi di Padova. Libretti d'Opera: Record 5080. Retrieved 5 July 2017 (in Italian).

- Synopsis based on Spadetta, Almerindo (1852). Don Checco, opera buffa in due atti. Tipografia F. S. Criscuolo (libretto printed for the premiere run).

- OCLC 949471267

External links

- Original libretto with side-by-side English translation

- Libretto adapted for an all-male cast, published in 1877 (in Italian)

- Libretto with the original prose adapted into verse by Carlo Cambiaggio, published c.1857 (in Italian)

- De Giosa's autograph score of Don Checco held in the library of the Conservatory of San Pietro a Majella

- Fiorito, Lorenzo (1 October 2014). "Don Checco, a comedy of errors in Neapolitan sauce". Bachtrack. (review of the 2014 performance in Naples with production photos)