Din-i Ilahi

The Dīn-i Ilāhī (Persian: دين إله, lit. "Religion of God")[1][2] or Divine Faith was a syncretic religion propounded by the Mughal emperor Akbar in 1582, intending to merge some of the elements of the religions of his empire, and thereby reconcile the differences that divided his subjects.[2] The elements were primarily drawn from Islam and Hinduism, but some others were also taken from Christianity, Jainism and Zoroastrianism.

| Din-i-Ilahi | |

|---|---|

| دین الٰہی | |

Akbar | |

| Type | Abrahamic and Dharmaic-influenced Syncretism |

| Leader | Akbar |

| Region | Indian subcontinent |

| Founder | Akbar |

| Origin | 1597 Fatehpur Sikri, Agra, Mughal Empire |

| Separated from | Sunni Islam |

| Defunct | Likely 1606 |

| Members | 21; also there were several influenced followers |

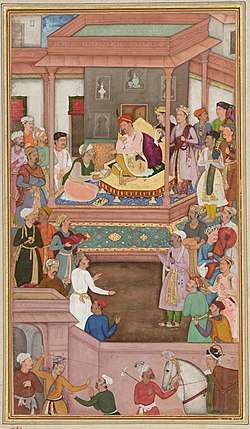

Akbar promoted tolerance of other faiths and even encouraged debate on philosophical and religious issues. That led to the creation of the Ibādat Khāna ("House of Worship") at Fatehpur Sikri in 1575. He had already repealed the jizya (tax on non-Muslims) in 1568. A religious experience while he was hunting in 1578 further increased his interest in the religious traditions of his empire.[3]

From the discussions held at the Ibādat Khāna, Akbar concluded that no single religion could claim the monopoly of truth. That inspired him to create the Dīn-i Ilāhī in 1582. Various pious Muslims, among them the Qadi of Bengal Subah and Shaykh Ahmad Sirhindi, responded by declaring it to be blasphemy to Islam. According to the renowned historian Mubarak Ali, Dīn-i Ilāhī is a name that was not used in Akbar's period. At the time, it was called Tawhid-i-Ilāhī ("divine monotheism"), as it is written by Abu Al Fazal, a court historian during the reign of Akbar.[4]

Dīn-i Ilāhī appears to have survived Akbar according to the Dabestān-e Mazāheb of Mubad Shah (Mohsin Fani). However, the movement never numbered more than 18 adherents.[5][6]

Despite Akbar's personal controversies, Dīn-i Ilāhī prohibits lust, sensuality, slander and pride, considering them sins. Piety, prudence, abstinence and kindness are the core virtues. The soul is encouraged to purify itself through yearning of God.[2] Celibacy is respected, and the slaughter of animals is forbidden. There are neither sacred scriptures nor a priestly hierarchy in the religion.[7]

In the 17th century, an attempt to re-establish Dīn-i Ilāhī was made by Shah Jahan's eldest son, Dara Shikoh,[8] but was prevented by his brother Aurangzeb who executed him,[9] and later compiled the Fatawa-e-Alamgiri and established Islamic Sharia law across the Indian Subcontinent.[10]

Ṣulḥ-i-kul

It has been argued that the theory of Dīn-i Ilāhī being a new religion was a misconception which arose because of erroneous translations of Abu'l-Fazl's work by later British historians.[11] However, it is also accepted that the policy of sulh-i-kul, which formed the essence of Dīn-i Ilāhī, was adopted by Akbar as a part of general imperial administrative policy. Sulh-i-kul means "universal peace".[12][13]

In practice, however, the Dīn-i Ilāhī functioned as a personality cult contrived by Akbar around his own person. Members of the religion were handpicked by Akbar according to their devotion to him. Because the emperor styled himself a reformer of Islām, arriving on Earth almost 1,000 years after the Prophet Muḥammad, there was some suggestion that he wished to be acknowledged as a prophet also.

Akbar is recorded by various conflicting sources as having affirmed allegiance to Islām and as having broken with Islām. His religion was generally regarded by his contemporaries as a Muslim innovation or a heretical doctrine; only two sources from his own time—both hostile—accuse him of trying to found a new religion. The influence and appeal of the Dīn-i Ilāhī were limited and did not survive Akbar, but they did trigger a strong orthodox reaction in Indian Islām.

Disciples

The initiated disciples of Dīn-i Ilāhī during emperor Akbar's time included (p. 186):[2]

- Birbal

- Abu'l-Fazl ibn Mubarak

- Qasim Khan

- Azam Khan

- Shaikh Mubarak

- Abdus Samad

- Mulla Shah Muhammad Shahadad

- Sufi Ahmad

- Mir Sharif Amal

- Sultan Khwaja

- Mirza Sadr-ud-Din

- Taki Shustar

- Shaikhzada Gosala Benarasi

- Sadar Jahan

- Sadar Jahan's first son

- Sadar Jahan's second son

- Shaikh Faizi

- Jafar Beig

References

- Din-i Ilahi - Britannica Online Encyclopedia

- Roy Choudhury, Makhan Lal (1997) [First published 1941], The Din-i-Ilahi, or, The religion of Akbar (4th ed.), New Delhi: Oriental Reprint, ISBN 978-81-215-0777-6

- Schimmel, Annemarie (2006) The Empire of the Great Mughals: History, Art and Culture, Reaktion Books, ISBN 1-86189-251-9

- Abu'l-Fazl ibn Mubarak (2010) [1902–39]. The Akbarnama of Abu'l-Fazl. Delhi: Low Price Publications. ISBN 81-7536-481-5.

- Din-i Ilahi - Britannica Online Encyclopedia

- THE DABISTÁN, OR SCHOOL OF MANNERS, Trans. DAVID SHEA and ANTHONY TROYER, 1843, Persian Literature in Translation, The Packard Humanities Institute

- Children's Knowledge Bank, Dr. Sunita Gupta, 2004

- Dara Shikoh Medieval Islamic Civilization: An Encyclopedia, by Josef W. Meri, Jere L Bacharach. Routledge, 2005. ISBN 0-415-96690-6. Page 195-196.

- "India was at a crossroads in the mid-seventeenth century; it had the potential of moving forward with Dara Shikoh, or of turning back to medievalism with Aurangzeb".Eraly, Abraham (2004). The Mughal Throne : The Saga of India's Great Emperors. London: Phoenix. p. 336. ISBN 0-7538-1758-6.

"Poor Dara Shikoh!....thy generous heart and enlightened mind had reigned over this vast empire, and made it, perchance, the garden it deserves to be made". William Sleeman (1844), E-text of Rambles and Recollections of an Indian Official p.272 - Jackson, Roy (2010). Mawlana Mawdudi and Political Islam: Authority and the Islamic State. Routledge. ISBN 9781136950360.

- Ali 2006, pp. 163–164

- "Why putting less Mughal history in school textbooks may be a good idea".

- "Finding Tolerance in Akbar, the Philosopher-King".