Demetrias

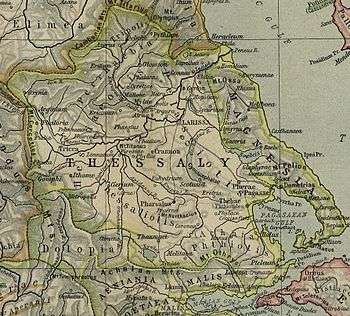

Demetrias (Ancient Greek: Δημητριάς) was a Greek city in Magnesia in ancient Thessaly (east central Greece), situated at the head of the Pagasaean Gulf, near the modern city of Volos.

History

It was founded in 294 BCE by Demetrius Poliorcetes, who removed thither the inhabitants of Nelia, Pagasae, Ormenium, Rhizus, Sepias, Olizon, Boebe and Iolcos, all of which were afterwards included in the territory of Demetrias.[1] It soon became an important place, and the favourite residence of the Macedonian kings. It was favourably situated for commanding the interior of Thessaly, as well as the neighbouring seas; and such was the importance of its position that it was called by Philip V of Macedon one of the three fetters of Greece, the other two being Chalcis and Corinth.[2][3]

In 196 BCE, the Romans, victorious in the Battle of Cynoscephalae over Philip V in the previous year, took possession of Demetrias and garrisoned the town.[4][5] Four years later the Aetolian League captured it by surprise. The Aetolians allied themselves with Antiochus III of the Seleucid Empire in the Roman–Seleucid War. This ended in the defeat of Antiochus.[6] After the return of Antiochus to Asia in 191 BCE, Demetrias surrendered to Philip, who was allowed by the Romans to retain possession of the place.[7] It continued in the hands of Philip and his successor till the over-throw of the Macedonian monarchy at the Battle of Pydna, 169 BCE.[8]

During Roman times it lost importance, but it was the capital of the Magnesian League. In Christian times some buildings were built, especially two churches, one in the northern port, called Basilica of Damokratia, and another one to the south of the city, outside the walls, known as the Cemetery Basilica. Under Roman Emperor Constantine the Great (ruled 306–337) it became a Christian episcopal see and is now a titular see of the Catholic Church.[9]

According to Procopius (De Aedificiis, 4.3.5), Demetrias was rebuilt by Justinian I (r. 527–565), but other evidence points to the possibility that "ancient urban life may have already come to an end by the beginning of the 6th century" (T.E. Gregory). Demetrias is mentioned by Hierocles in the sixth century.[10] Its territory was settled by the Slavic tribe of the Belegezitai in the 7th/8th centuries, raided and sacked by the Saracens in 901/2, and by rebels during the Uprising of Peter Delyan in 1040.[11]

Following the Fourth Crusade, the town was granted to the exiled Byzantine empress Euphrosyne Doukaina Kamatera, and after her death in 1210 to Margaret of Hungary, the widow of the King of Thessalonica, Boniface of Montferrat.[11] The city came under the rule of Manuel Komnenos Doukas ca. 1240, but was de facto controlled by a branch of the Melissenos family.[11] In the 1270s, the Byzantines scored an important victory against the Venetians and the Lombard barons of Euboea at the Battle of Demetrias.

The Catalan Company sacked the town in 1310 and kept it until 1381 at least, but from 1333 on, it began to be abandoned for neighbouring Volos. It was finally captured by the Ottoman Empire in 1393.[11]

Archaeology

The site of Demetrias is at a place called Aivaliotika (Αϊβαλιώτικα) in the municipality of Volos.[12][13]

The ancient town was described by William Martin Leake, who visited the site in the early 19th century, as occupying "the southern or maritime face of a height, now called Gorítza, which projects from the coast of Magnesia, between 2 and 3 miles [3 to 5 km] to the southward of the middle of Volo. Though little more than foundations remains, the inclosure of the city, which was less than 2 miles [3 km] in circumference, is traceable in almost every part. On three sides the walls followed the crest of a declivity which falls steeply to the east and west, as well as towards the sea. To the north the summit of the hill, together with an oblong space below it, formed a small citadel, of which the foundations still subsist. A level space in the middle elevation of the height was conveniently placed for the central part of the city. The acropolis contained a large cistern cut in the rock, which is now partly filled with earth . . . . Many of the ancient streets of the town are traceable in the level which lies midway to the sea, and even the foundations of private houses: the space between one street and the next parallel to it, is little more than 15 feet [5 m]. About the centre of the town is a hollow, now called the lagúmi or mine, where a long rectangular excavation in the rock, 2 feet wide [0.6 m], 7 deep [2.1 m], and covered with flat stones, shows by marks of the action of water in the interior of the channel that it was part of an aqueduct, probably for the purpose of conducting some source in the height upon which stood the citadel, into the middle of the city."[14]

The site, about 3 km south of Volos, was excavated from the end of the 19th century. Remains of the walls (about 11 km) and the acropolis that was to the northwest in the highest point of the city are preserved. Also uncovered were the theater, the Heroon (a temple above the theater), an aqueduct, the sacred agora (with a temple and the administrative center of the city), and the Anaktoron (royal palace) east of the city on the top of a hill, which was occupied until the middle of second century BCE, and later used by the Romans as a cemetery.[15][16]

See also

References

- Strabo. Geographica. ix. p.436. Page numbers refer to those of Isaac Casaubon's edition.

- Polybius. The Histories. 17.11.

- Livy. Ab Urbe Condita Libri (History of Rome). 32.37.

- Polybius. The Histories. 18.28.

- Livy. Ab Urbe Condita Libri (History of Rome). 33.31.

- Livy. Ab Urbe Condita Libri (History of Rome). 35.34, 43.

- Livy. Ab Urbe Condita Libri (History of Rome). 36.33.

- Livy. Ab Urbe Condita Libri (History of Rome). 44.13.

- Annuario Pontificio 2013 (Libreria Editrice Vaticana 2013 ISBN 978-88-209-9070-1), "Sedi titolari", p. 880

- Hierocles. Synecdemus. p. 642, ed. Wesseling.

- Gregory, Timothy E. (1991). "Demetrias". In Kazhdan, Alexander (ed.). The Oxford Dictionary of Byzantium. Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press. pp. 603–604. ISBN 978-0-19-504652-6.

- Lund University. Digital Atlas of the Roman Empire.

- Richard Talbert, ed. (2000). Barrington Atlas of the Greek and Roman World. Princeton University Press. p. 55, and directory notes accompanying.

- Leake, Northern Greece, vol. iv. p. 375, et seq.

- https://www.gtp.gr/TDirectoryDetails.asp?ID=39125

- http://odysseus.culture.gr/h/3/eh351.jsp?obj_id=2377

![]()