Diego de Argumosa

Diego Manuel de Argumosa y Obregón[1][2] (July 7, 1792 – April 23, 1865) was a Spanish doctor and the chair of surgery of the School of Medicine at the University of Madrid. Known as "the restorer of Spanish surgery,"[3] he was an innovator in the field of medical science. He is recognized for running the first clinical trial and for encouraging the use of anesthesia in Spain, introducing ether in 1847.[4]

Diego de Argumosa | |

|---|---|

Diego de Argumosa | |

| Born | Diego de Argumosa y Obregón July 7, 1792 Villapresente, Cantabria, Spain |

| Died | April 23, 1865 (aged 72) Torrelavega, Cantabria, Spain |

| Nationality | Spanish |

| Alma mater | University of Alcalá |

| Occupation | Surgeon |

Argumosa gained much of his experience and knowledge serving as a doctor during the Peninsular War at the San Rafael Hospital in Santander, Spain. In addition to his medical innovations, he was known for providing care in a famous case where the Spanish nun Sor Patrocinio claimed to suffer from stigmata.[5]

Argumosa was a member of the Progressive Party, and he was the second mayor of Madrid and the deputy for the province of Madrid in 1836 and 1837.[6] He was appointed as the physician to Queen Isabel II, a position he never chose to accept.[7]

After the death of his family and his retirement at the age of 62, Argumosa retired to his hometown. He later died in Torrelavega, Cantabria, Spain.

Life

Diego de Argumosa was born on 7 July 1792 in Villapresente, Cantabria, Spain. His parents were both hidalgos: Juan Antonio de Argumosa, a doctor, and Ursula Obregón.[8] Diego studied at the Colegio de los Padres Escolapios de Villacarriedo (College of the Piarists of Villacarriedo) in Cantabria.[6]

During the Peninsular War, he joined the Third Battalion of Marksmen of Cantabria,[6] where he worked as a doctor attending to the wounded at the Military Section of the San Rafael Hospital in Santander.[9] He also accompanied the troops when they marched through the mountains; this deformed his feet, and caused him to limp for the rest of his life.[8]

When the war ended in 1814, Argumosa earned his bachelor's degree from the University of Alcalá. He later enrolled in the Surgical College of San Carlos in Madrid and earned his surgical license. In 1820 he earned his doctorate with his thesis, De prognosis in febribus acutis (Prognosis of acute febrile diseases). In 1821, he began working as an interim professor in the Surgical College of Burgos, where he stayed for two years. He then returned to Madrid, where he became a professor of dissection. In addition to his work, he cared for his mother and brothers, as his father had been exiled to London for political reasons. Because he had little experience in teaching, his early classes followed the teachings of Dr. Roche, a French surgeon who wrote a book on medicine and surgery that Argumosa would later translate into Spanish in 1828.[10] He continued until 1829, when he became the Chair of Surgery at the College of San Carlos,[3] then later worked at the surgical clinic.[9] During those years he married Micaela Adán, the daughter of sculptor Juan Adán Morlán,[11] and had three children: Diego, who died when he was nine years old, and Isabel and Natalia.

In around 1848, Argumosa publicly confronted Joaquín Hysern for writing a book based on his classes that he felt was incomplete and full of errors. In 1850, he published some articles in a newspaper called La Unión, in which he called professors José María López and Manuel Soler "university prevaricators," and they filed complaints against him. Argumosa was acquitted of libel charges but found guilty of making insults, and sentenced to two years of exile, a fine of 100 duros, and suspension of his office and political rights during the sentence.[10]

After the rapid and closely timed deaths of his two daughters, Arugmosa retired on January 27, 1854 to Villapresente.[9] Argumosa died in Torrelavega on April 23, 1865.

Innovations

Argumosa introduced ether-induced anesthesia to Spain on 13 January 1847,[12][13] only three months after John Collins Warren and William T. G. Morton first demonstrated its use in Boston, and only months after it was tested by François Magendie at the Paris Academy of Medicine.[14] He attached a cow's bladder containing one ounce of ether to the patient's mouth with a metal cannula, which they would breathe.[6] Afterwards, he also used chloroform to anesthetize the patient.

Argumosa also developed new surgical techniques, and improved upon existing surgical practices. He changed the position of the patient during surgery, operating on them when they were lying down instead of the seated position that was generally used, so that they could better withstand the pain of the procedure.[10] He developed new techniques to amputate the thigh and the anal fistula, which he described in his monographs.[15] He invented the "basted suture," which he used to treat aneurysms. He also was among the first to practice phlebotomy, suturing the tear in a vein.[6] He developed an intestinal suture that could be naturally expelled from the channel through which it was placed, which did not necessitate the laparotomic incision that was previously required for suture removal.[10]

Some of his innovations were in the field of general medicine: he was an early practitioner of asepsis, taking exceptional care to clean his hands, instruments, and the operating room. He isolated patients while they were undergoing surgery, instead of operating in a room with other patients.[16][10]

He was also an innovator in the field of otorhinolaryngology. He developed the blepharoplasty technique to remove tumors in the lower eyelid, cancers of the cheekbone, and to treat the loss of the outer part of the eyelids. He developed the cheiloplasty technique to treat lip cancers. He improved the rhinoplasty technique.[6][17] He also developed the syringotome, a special type of scalpel.[7]

Among his developments in urology were his technique to puncture the bladder (cytotomy), various methods of removing urinary calculi, external and internal urethrotomies, the subcutaneous ligation of varicocele veins using the fisherman's knot, and genital operations.[3][17]

Argumosa also contributed to the field of arthrology, although it was his students who developed upon his work. He founded a school that was continued by two of his primary students: Juan Creus, a forefather of taurotraumatology (bullfighting injuries), and Melchor Sánchez de Toca.[3]

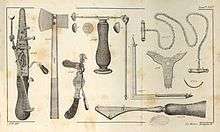

In 1854, he retired to Torrelavega to write Resumen de Cirugía (Summary of Surgery), which was published in 1856. The work described the general knowledge of surgery at that time and all of his innovations, and was accompanied by illustrations and descriptions of the surgical instruments that he had created for his procedures.[6]

Sor Patrocinio's stigmata

In 1830, Spanish nun Sor Patrocinio claimed to be afflicted with stigmata, which appeared on her hands, feet, and side. Her fame spread quickly, and before she turned 25 she was considered a living saint. Religious people flocked to the convent where she lived: common people, aristocrats, and courtesans of Queen Isabel II and her husband Francis, Duke of Cádiz.[18]

In 1835, Argumosa was one of the doctors tasked with studying the nun's stigmata.[19] They disinfected and treated the wounds, and in less than three weeks all were healed and the nun was discharged from their care. The nun was banished to Talavera de la Reina. Despite the fact that both religious and civil authorities agreed with the decision that the stigmata were fraudulent, some did not accept Argumosa's diagnosis.[10][13] However, during the case, a friar confessed that, while traveling with him to Rome to found new convents, the nun had given him a sachet containing a substance that would cause a small ulcer when applied to the body.[10]

Distinctions

- Member of the National Royal Academy of Medicine (1831)

- Decoration of King Fernand VII (1844)

- Commander of the Royal and Distinguished Spanish Order of Carlos III (1852)

- Member of honor of the Cantabrian Academy of Medicine (1980)

- Academic in the Royal Academy of Sciences and Arts of Barcelona

- Member of the National Academy of Medicine of Mexico

- Member of the Physicians Society of Athens

- Decorated with the Great Cross of Charity

Notes

- Bustamente y Urrutia 1959, p. 555.

- Romanillo & Cortina, p. 259.

- Asociación Española de Urología.

- Hospital de Clínicas Caracas.

- Perera y Prast 1968, p. 220.

- Fresquet 2009.

- Perera y Prast 1968, p. 219.

- Perera y Prast 1968, p. 209.

- Government of Cantabria.

- Vázquez de Quevedo 2005.

- García del Moral 1906, p. 19.

- Salud Madrid.

- Urrero 2008.

- López Piñero 2002, p. 566.

- Perera y Prast 1968, p. 218.

- Perera y Prast 1968, p. 215.

- López Piñero 2002, p. 563.

- Enciclopedia Franciscana.

- Causa Formada contra D. Maria de los Dolores Quiroga 1837.

References

- Associación Española de Urología. "Diego de Argumosa y Obregón (1792–1865)". Historia de la Urología Española (in Spanish). Retrieved 7 January 2017.

- Bustamente y Urrutia, José María de (1959). Catálogos de la Biblioteca Universitaria (in Spanish). University of Santiago de Compostela.

- Causa Formada contra D. Maria de los Dolores Quiroga (Report). Madrid. 1837.

- Fresquet, José L. (2009). "Diego Argumosa y Obregón (1792–1865)". Historia de la Medicina. Retrieved 7 January 2017.

- García del Moral, Jose (1906). Galería de Escritores Médicos Montañeses: Ensayo Bio-Bibliográfico.

- Government of Cantabria. "Cantabria 102 Municipios". Retrieved 7 January 2017.

- Hospital de Clínicas Caracas. "Historia de la anestesia" [History of anesthesia] (in Spanish). Archived from the original on 13 March 2013. Retrieved 7 January 2017.

- López Piñero, José María (2002). La Medicina en la Historia. La Esfera de los Libros. ISBN 9788497340892.

- "María de los Dolores y Patrocinio". Enciclopedia Franciscana. 2014.

- Perera y Prast, Arturo (1968). "La atormentada vida del doctor Argumosa" [The troubled life of Dr. Argumosa]. Anales de la Real Academia Nacional de Medicina (in Spanish). 85.

- Salud Madrid. "...en 1846 se hizo la primera demostración pública del uso de la anestesia general en una intervención quirúrgica" [...in 1846 the first public demonstration of the use of general anesthesia in surgery was given]. Retrieved 8 January 2017.

- Romanillo, Alfonso Moure; Cortina, Manuel Suárez, eds. (1995). De la montaña a Cantabria: la construcción de una comunidad autónoma [From the mountain to Cantabria: the construction of an autonomous community] (in Spanish). University of Cantabria. ISBN 84-8102-112-1.

- Urrero, Guzmán (7 August 2008). "Diego de Argumosa y Obregón". The Cult. Retrieved 8 January 2017.

- Vázquez de Quevedo, Francisco (2005). "Diego de Argumosa. Restaurador de la cirugía española. Retrospectiva" [Diego de Argumosa. Restorer of Spanish surgery. Retrospective]. La Revista de Cantabria. Caja Cantabria. 121 (October–December): 32–35. ISSN 1988-9070.