Die Gedanken sind frei

"Die Gedanken sind frei" (Thoughts are free) is a German song about freedom of thought. The original lyricist and the composer are unknown, though the most popular version was rendered by Hoffmann von Fallersleben in 1842.

Text

The idea represented in the title—that thoughts are free—was expressed in antiquity[1] and became prominent again in the Middle Ages, when Walther von der Vogelweide (c.1170–1230) wrote: joch sint iedoch gedanke frî ("yet still thoughts are free").[2] In the 12th century, it is thought that Austrian minnesinger Dietmar von Aist composed the song "Gedanke die sint ledic vrî" ("only thoughts are free"). About 1229, Freidank wrote: diu bant mac nieman vinden, diu mîne gedanke binden ("this band may no one twine, that will my thoughts confine").

The text as it first occurred on leaflets about 1780 originally had four strophes, to which a fifth was later added. Today, their order may vary. An early version in the shape of a dialogue between a captive and his beloved was published under the title "Lied des Verfolgten im Thurm. Nach Schweizerliedern" ("Song of the persecuted in the tower. After Swiss songs") in Achim von Arnim and Clemens Brentano's circa 1805 folk poetry collection Des Knaben Wunderhorn, Vol. III.

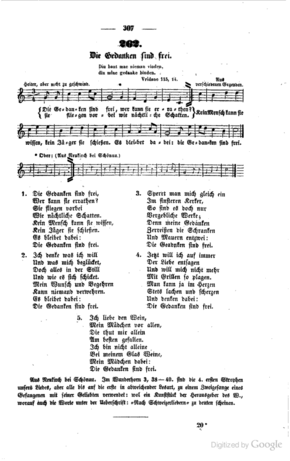

The text and the melody can be found in Lieder der Brienzer Mädchen (songs of the girls from Brienz), printed in Bern, Switzerland, between 1810 and 1820. It was adopted by Hoffmann von Fallersleben in his Schlesische Volkslieder mit Melodien (Silesian folk songs with melodies) collection published by Breitkopf & Härtel in 1842, who referred to it as "from Neukirch bei Schönau".

Lyrics

Die Gedanken sind frei, wer kann sie erraten,

sie fliegen vorbei wie nächtliche Schatten.

Kein Mensch kann sie wissen, kein Jäger sie schießen

mit Pulver und Blei: Die Gedanken sind frei!

Ich denke was ich will und was mich beglücket,

doch alles in der Still', und wie es sich schicket.

Mein Wunsch und Begehren kann niemand verwehren,

es bleibet dabei: Die Gedanken sind frei!

Und sperrt man mich ein im finsteren Kerker,

das alles sind rein vergebliche Werke.

Denn meine Gedanken zerreißen die Schranken

und Mauern entzwei: Die Gedanken sind frei!

Drum will ich auf immer den Sorgen entsagen

und will mich auch nimmer mit Grillen mehr plagen.

Man kann ja im Herzen stets lachen und scherzen

und denken dabei: Die Gedanken sind frei!

Ich liebe den Wein, mein Mädchen vor allen,

sie tut mir allein am besten gefallen.

Ich sitz nicht alleine bei meinem Glas Weine,

mein Mädchen dabei: Die Gedanken sind frei!

Thoughts are free, who can guess them?

They fly by like nocturnal shadows.

No person can know them, no hunter can shoot them

with powder and lead: Thoughts are free!

I think what I want, and what delights me,

still always reticent, and as it is suitable.

My wish and desire, no one can deny me

and so it will always be: Thoughts are free!

And if I am thrown into the darkest dungeon,

all these are futile works,

because my thoughts tear all gates

and walls apart: Thoughts are free!

So I will renounce my sorrows forever,

and never again will torture myself with whimsies.

In one's heart, one can always laugh and joke

and think at the same time: Thoughts are free!

I love wine, and my girl even more,

Only her I like best of all.

I'm not alone with my glass of wine,

my girl is with me: Thoughts are free!

The rhyme scheme of the lyrics is a – B / a – B / C – C / d – d where capital letters indicate two-syllable feminine rhymes.

Melody

Adaptations

Since the days of the Carlsbad Decrees and the Age of Metternich, "Die Gedanken sind frei" was a popular protest song against political repression and censorship, especially among the banned Burschenschaften student fraternities. In the aftermath of the failed 1848 German Revolution the song was banned. The Achim/Brentano text was given a new musical setting for voice and orchestra by Gustav Mahler in his 1898 Des Knaben Wunderhorn collection.

The song was important to certain anti-Nazi resistance movements in Germany.[3] In 1942, Sophie Scholl, a member of the White Rose resistance group, played the song on her flute outside the walls of Ulm prison, where her father Robert had been detained for calling the Nazi dictator Adolf Hitler a "scourge of God". Earlier, in 1935, the guards at the Lichtenburg concentration camp had ordered prisoners to stage a performance in celebration of Hitler's 46th birthday; the imprisoned lawyer Hans Litten recited "Die Gedanken sind frei" in response.[4]

The Weavers recorded the song at a live concert in the 1950s. Pete Seeger also recorded the song, solo, back in the 1950s. The Limeliters recorded the song in 1962 on their Folk Matinee album. Pete Seeger recorded the song once more in his Dangerous Songs!? album in 1966. Norwegian composer Alf Cranner translated and recorded it as "Din tanke er fri" in 1985. Parts of the poem were also taken as the basis of a song by the Brazilian Girls on their self-titled 2005 album.

In popular culture

"Die Gedanken sind frei" was used as the theme and was sung by the Allied prisoners of war in the 1971 TV movie The Birdmen, which was a fictionalized dramatization of an attempt to escape from the German Oflag IV-C camp at Colditz Castle in World War II. It was featured in the 1998 German movie 23 about the hacker Karl Koch. This melody was played by a violinist in the film The Book Thief.

In Canadian author Jean Little's 1972 book From Anna the song is used to represent the freedom the titular character's father craves for his children, and as such figures predominantly into the plot at the beginning of the novel.

"Die Gedanken sind frei" is a track by the German band Megaherz on their Wer bist du? album.

The text of "Die Gedanken sind frei" has been used in the video game Orwell as a plot device, while the first verse of the song is played during the ending.

Notes

- Cicero: Liberae sunt (...) nostrae cogitationes, ("Free are our thoughts") Pro Milone, XXIX. 79., 52 BC

- "Der Keiser als Spileman", Walther von der Vogelweide

- Melon, Ruth Bernadette. Journey to the White Rose in Germany. Dog Ear Publishing, 2007. ISBN 1-59858-249-6. p. 122.

- Jon Kelly (19 August 2011). "Hans Litten: The man who annoyed Adolf Hitler". BBC News. Retrieved 19 August 2011.

External links

| German Wikisource has original text related to this article: |

- Variant German lyrics and English translation

- "Die Gedanken sind frei", ingeb.org

- Four-part setting for mixed chorus (SATB): Scores at the International Music Score Library Project (IMSLP)

- Choral version on YouTube