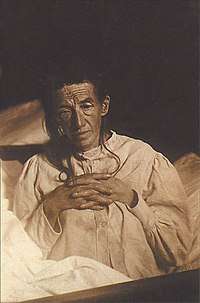

Auguste Deter

Auguste Deter (German pronunciation: [aʊ̯ˈɡʊstə ˈdeːtɐ]; 16 May 1850 – 8 April 1906) was a German woman notable for being the first person to be diagnosed with Alzheimer's disease.

Auguste Deter | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | Johanna Auguste Caroline Hochmann 16 May 1850 Kassel, Germany |

| Died | 8 April 1906 (aged 55) Frankfurt, Germany |

| Nationality | German |

| Known for | First diagnosis of Alzheimer's |

| Spouse(s) | Carl August Wilhelm Deter |

Life

Her father was Johann Hohmann. She married Carl August Wilhelm Deter on May 1, 1873 and together they had one daughter.

Onset of disease

During the late 1890s, she started showing symptoms of dementia, such as loss of memory, delusions, and even temporary vegetative states. She would have trouble sleeping, drag sheets across the house, and scream for hours in the middle of the night.

As a railway worker, Carl was unable to provide adequate care for his wife. He had her admitted to a mental institution, the Institution for the Mentally Ill and for Epileptics (Irrenschloss) in Frankfurt, Germany on 25 November 1901. There, she was examined by Dr. Alois Alzheimer.

Treatment

Dr. Alzheimer asked her many questions, and later asked again to see if she remembered. He told her to write her name. She tried to, but would forget the rest and repeat: "I have lost myself." (German: "Ich habe mich verloren.") He later put her in an isolation room for a while. When he released her, she would run out screaming, "I will not be cut. I do not cut myself."[1]

After many years, she became completely demented, muttering to herself. She died on 8 April 1906. More than a century later, her case was re-examined with modern medical technologies, where a genetic cause was found for her disease by scientists from Gießen and Sydney. The results were published in the journal The Lancet Neurology. According to this paper, a mutation in the PSEN1 gene was found, which alters the function of gamma secretase, and is a known cause of early-onset Alzheimer's disease.[2] However, the results could not be replicated in a more recent paper published in 2014 where "Auguste D's DNA revealed no indication of a nonsynonymous hetero- or homozygous mutation in the exons of APP, PSEN1, and PSEN2 genes comprising the already known familial AD mutations."[3]

Alzheimer concluded that she had no sense of time or place. She could barely remember details of her life and frequently gave answers that had nothing to do with the question and were incoherent. Her moods changed rapidly between anxiety, mistrust, withdrawal and 'whininess'. They could not let her wander around the wards because she would accost other patients who would then assault her. It was not the first time that Dr. Alzheimer had seen a complete degeneration of the psyche in patients, but previously the patients had been in their seventies. Ms. Deter piqued his curiosity because she was much younger. In the weeks following, he continued to question her and record her responses. She frequently responded, "Oh, God!", and, "I have lost myself, so to say". She seemed to be consciously aware of her helplessness. Alzheimer called it the "Disease of Forgetfulness".

Death and legacy

In 1902, Alzheimer left the "Irrenschloss" (Castle of the Insane), as the Institution was known colloquially, to take up a position in Munich, but made frequent calls to Frankfurt inquiring about Deter's condition. On 9 April 1906, Alzheimer received a call from Frankfurt that Auguste Deter had died. He requested that her medical records and brain be sent to him. Her chart recorded that in the last years of her life, her condition had deteriorated considerably. Her death was the result of sepsis caused by an infected bedsore. On examining her brain, he found senile plaques and neurofibrillary tangles. These would be the hallmark of Alzheimer's Disease as scientists know it today. Auguste would have been diagnosed with early-onset Alzheimer's disease if seen by a current-day doctor.

Rediscovery of medical record

In 1996, Dr. Konrad Maurer and his colleagues, Drs. Volk and Gerbaldo, rediscovered the medical records of Auguste Deter.[4] In these documents, Dr. Alzheimer had recorded his examination of his patient, including her answers to his questions:

- "What is your name?"

- "Auguste."

- "Family name?"

- "Auguste."

- "What is your husband's name?" - she hesitates, finally answers:

- "I believe ... Auguste."

- "Your husband?"

- "Oh, no no no."

- "How old are you?"

- "Fifty-one."

- "Where do you live?"

- "Oh, you have been to our place."

- "Are you married?"

- "Oh, I am so confused."

- "Where are you right now?"

- "Here and everywhere, here and now, you must not think badly of me."

- "Where are you at the moment?"

- "We will live there."

- "Where is your bed?"

- "Where should it be?"

Around midday, Frau Auguste D. ate pork and cauliflower.

- "What are you eating?"

- "Spinach." (She was chewing meat.)

- "What are you eating now?"

- "First I eat potatoes and then horseradish."

- "Write a '5'."

- She writes: "A woman"

- "Write an '8'."

- She writes: "Auguste" (While she is writing she repeatedly says, "I have lost myself, so to say.")

References

- Maurer, Konrad; Volk, Stephan; Gerbaldo, Hector (1997). "Auguste D and Alzheimer's disease". The Lancet. 349 (9064): 1546–9. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(96)10203-8.

- Müller, Ulrich; Winter, Pia; Graeber, Manuel B (2013). "A presenilin 1 mutation in the first case of Alzheimer's disease". The Lancet Neurology. 12 (2): 129–30. doi:10.1016/S1474-4422(12)70307-1. PMID 23246540.

- Rupp, Carsten; Beyreuther, Konrad; Maurer, Konrad; Kins, Stefan (2014). "A presenilin 1 mutation in the first case of Alzheimer's disease: Revisited". Alzheimer's & Dementia. 10 (6): 869–72. doi:10.1016/j.jalz.2014.06.005. PMID 25130656.

- Deutsche Alzheimer Gesellschaft Archived 2011-07-18 at the Wayback Machine

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Alois Alzheimer. |

- Works by or about Auguste Deter at Internet Archive

- Who Named It? – Alois Alzheimer

- Alzheimer's: 100 years on

- Alois Alzheimer's Biography. International Brain Research Organization

- Ludwig-Maximilians-University Munich, Laboratory for Neurodegenerative Disease Research – Prof. Dr. Christian Haass

- Bibliography of secondary sources on Alois Alzheimer and Alzheimer's disease, selected from peer-reviewed journals.

- Graeber Manuel B. "Alois Alzheimer (1864–1915)". International Brain Research Organization