Destined to Witness

Destined to Witness: Growing Up Black in Nazi Germany (ISBN 978-0060959616), is an autobiographical book by Hans J. Massaquoi.

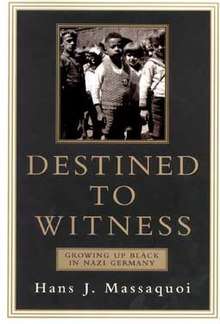

Book cover | |

| Author | Hans J Massaquoi |

|---|---|

| Subject | Germany during World War II |

| Genre | Autobiography |

| Publisher | W. Morrow |

Published in English | 1999 |

| Pages | xvi, 443 pages |

| ISBN | 0688171559 |

| OCLC | 41464909 |

Content

In his 1999 autobiography the author, former managing editor of Ebony, tells the story of his growing up in Hamburg. He was born in 1926 as son of a German mother and a Liberian law student, the only independent black African state at that time apart from Ethiopia. His grandfather was the Liberian consul-general to Hamburg. When his father and grandfather went back to Liberia in 1929, his mother decided to stay in Germany. She made her living working as a nurse, and she and the little boy had to move from the elegant villa to a modest cold-water apartment in the workers’ quarter Barmbek. He was shunned but was never a target of Nazi persecution like Jews and Roma were. He was rebuffed when he applied for membership in the Hitler Jugend (Hitler Youth), while every young male Aryan German was obliged to be a member. Because he was underweight, he was not drafted to join the German Army.[1]

Background

In the 1930s only a few black people lived in Germany, most of them in the Rhine area, children of German mothers and French-African soldiers. During World War I France had recruited troops from its African colonies, mainly from Senegal. These children in the French-occupied Rhineland were called Franzosenkinder (Frenchmen's children). In the northern part of Germany black people were so rare that most people had never seen one.

Nazi Germans considered mixed race children, like Massaquoi, a threat to the racial purity they sought. Many black and mixed race children were rounded up and sterilized or used for scientific experiments. Some were held in concentration camps and some simply “disappeared."[2] Massaquoi was fortunate enough not to be detained by the Nazis and explains that, “blacks were so few in numbers that they were relegated to low-priority status in the Nazis' lineup for extermination."[3]

In the book, Hans Massaquoi describes his childhood dream to join the Hitler Youth. The Hitler Youth was established in 1926 to recruit soldiers, but in 1933 it transitioned to a new role teaching children loyalty to Hitler and Nazism. In German schools like the one Massaquoi attended, children were taught “love for Hitler, obedience to state authority, militarism, racism, and anti-Semitism.”[4] When Massaquoi describes his longing to be a “good German” like he was taught in school, and is greatly disappointed when he is told he cannot join the Hitler Youth like his classmates who all “had cool uniforms and they did exciting things — camping, parades, playing drums."[3]

Translation to German and screenplay

Destined to Witness, in German titled Neger, Neger, Schornsteinfeger (Negro, Negro, Chimney Sweep), was a great success in Germany, remaining on top of the bestselling list of the German weekly Der Spiegel for a couple of months. A screenplay has been adapted from the book and movie shooting started in 2005. The film was run first on October 1 and 2 in 2006 as a two-parter on German ZDF TV channel.

See also

References

- "Growing Up as a Black Kid in Nazi Germany". Vice Magazine. Retrieved May 5, 2016.

- "Blacks During the Holocaust". Holocaust Encyclopedia. United States Holocaust Memorial Museum. Retrieved March 30, 2016.

- "Hans Massaquoi dies at 87; wrote of growing up black in Nazi Germany". The Los Angeles Times. January 22, 2013. Retrieved March 30, 2016.

- "Indoctrinating Youth". Holocaust Encyclopedia. United States Holocaust Memorial Museum. Retrieved March 30, 2016.

External links

- Neger, Neger, Schornsteinfeger (2006) on IMDb

- Fischer, Audrey (March 2000). "Growing Up Black in Nazi Germany". Library of Congress Information Bulletin. 59 (3).