Desmond Piers

Rear Admiral Desmond William Piers, CM DSC CD (June 12, 1913 – November 1, 2005) was a rear-admiral in the Royal Canadian Navy. Born in Halifax and long-time resident of Chester, Nova Scotia, Piers served in the RCN from 1932 to 1967. In 1930, he was the first graduate of the Royal Military College of Canada (student # 2184) to join the RCN. He became agent general of Nova Scotia in the United Kingdom in 1977.

Desmond William Piers | |

|---|---|

Lt-Cdr Desmond W. Piers on the bridge of HMCS Restigouche, 21 April 1944 | |

| Nickname(s) | Debby |

| Born | June 12, 1913 Halifax, Nova Scotia |

| Died | November 1, 2005 (aged 92) Halifax, Nova Scotia |

| Allegiance | |

| Service/ | |

| Years of service | 1932–1967 |

| Rank | Rear Admiral |

| Commands held | HMCS Restigouche & 4th Canadian Escort Group (1941–1943); HMCS Algonquin (1944–1945 & 1956–1957); 1st Canadian Destroyer Squadron (1956–1957); Royal Military College (1957) |

| Battles/wars | World War II

|

| Awards | DSC; CM; CD and bar; Hon D.sc.Mil (1978); Klj[1]Freeman of the City of London (1978) |

| Other work | Agent-General for Nova Scotia in the UK and Europe (1977–1979); Chairman Canadian Corps of Commissionaires (Nova Scotia Division) |

Rear Admiral Piers is best known for his courageous actions in 1944 when, as the 30-year-old Commanding Officer of HMCS Algonquin, he directly participated in the invasion in France where he guided his ship and her crew through the conflagration of D-Day. In recognition of his actions he received the Légion d'Honneur, France's highest recognition for bravery in military action and service. He was also awarded the Distinguished Service Cross for his vigorous and invaluable service at sea during the Battle of the Atlantic.

Convoy SC 107

Piers was captain of the Canadian destroyer HMCS Restigouche from June 1941 (previously her First Lieutenant), during the battle to maintain the critical convoy routes to Britain. He was at the centre of a crisis in this battle. In October, 1942 Piers commanded escort group C4 (Restigouche and six corvettes) which was to escort the slow convoy SC107, from Sydney, Nova Scotia to Liverpool.

At the time, Canadian escort ships were regarded as inferior to their British equivalents and they were generally assigned to the slower, more vulnerable convoys. On this occasion, Restigouche was the only ship of Piers' group with working radar and direction finding equipment, both necessary to locate u-boats. In the circumstances, exacerbated by a failure to reroute the convoy away from the u-boats, it is unsurprising that the convoy, once found, would be severely mauled, losing 15 of its 42 ships.[2]

This level of losses was unsustainable and Admiral Sir Percy Noble, the then Commander-in-Chief, Western Approaches, insisted that Canadian escorts immediately be withdrawn for training or reassigned to less vulnerable routes. Although Piers received criticism for his group's performance, he had been aggressive in the convoy's defence. This was recognised by the award of the Distinguished Service Cross, some months later[note 1][3]

On September 26, 1943, Piers played a key role in an attempt by the Royal Canadian Navy and Canadian Army to trap a German submarine sent to pick up escaping prisoners of war at Pointe de Maisonnette, New Brunswick. The attempted escape was codenamed Operation Kiebitz by the German authorities. Only one prisoner, Wolfgang Heyda, made it from Bowmanville to Pointe de Maisonnette. Piers, after questioning him at the lighthouse, unmasked Heyda despite his initial denials. Recollecting the event after the war, Piers remarked, "I offered my regrets, but I had to return him to detention. I telephoned the RCMP. They came in a car and, a few moments later, I handed him over to them."[4] While none of the POW's got away, the submarine sent to pick them up was able to escape, only to be sunk a few weeks later.[5]

Post-war

Piers returned to the Royal Military College of Canada as Commandant in 1957.

In 1967, Piers retired to his home in Chester, Nova Scotia, doing community work until 1977 when he was appointed Agent General of Nova Scotia in London. This appointment entailed the support abroad of Nova Scotia's interests. In this role, he promoted the province's use of tidal energy. In the following year, 1978, he was made a Freeman of the City of London.[3]

To Desmond's seven grandchildren, he was always referred to as Grandeb and will always be remembered as the one engaging in musicals and small plays with the grandchildren. He never gave up a chance to teach them how to play the harmonica, as it was one of his favourite hobbies. He was a true inspiration to everyone. Desmond "Debby" Piers died in Halifax, Nova Scotia on 1 November 2005. He had married Janet Macneill in 1941, the couple had had one stepdaughter Anne.[6]

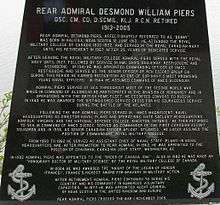

On June 2, 2007 a memorial monument in recognition of Rear Admiral Desmond William Piers was placed outside his Chester home. It can be seen on Front Street, down by the ocean in Chester, Nova Scotia.

See also

Notes

- The citation for the award said: "This officer has served continuously in His Majesty's Canadian destroyers since the commencement of hostilities. As Senior Officer of Convoy Escort Groups in the North Atlantic, he has, by his vigorous leadership and aggressive attack, been an inspiration to those under his command."

References

- http://www.rcnvr.com/P%20-%20RCN%20-%20WW2.php Desmond Piers Biography

- van der Vat, Dan (22 November 2005). "Rear Admiral Desmond Piers". The Guardian. Retrieved 4 May 2010.

- "Rear-Admiral 'Debby' Piers". Telegraph Group Limited. 15 November 2005. Retrieved 4 May 2010.

- https://web.archive.org/web/20080108064305/http://www.mnq-nmq.org/english/vivez/impacts/operation.htm

- Rodney J. Martin, Rendezvous at the Maisonnette Point Lighthouse, Lighthouse Digest April 2004 http://www.lhdigest.com/Digest/StoryPage.cfm?StoryKey=1917

- Houterman, Hans. "Royal Canadian Navy (RCN) Officers 1939-1945". unithistories. Retrieved 4 May 2010.

- 4237 Dr. Adrian Preston & Peter Dennis (Edited) "Swords and Covenants" Rowman And Littlefield, London. Croom Helm. 1976.

- H16511 Dr. Richard Arthur Preston "To Serve Canada: A History of the Royal Military College of Canada" 1997 Toronto, University of Toronto Press, 1969.

- H16511 Dr. Richard Arthur Preston "Canada's RMC - A History of Royal Military College" Second Edition 1982

- H1877 R. Guy C. Smith (editor) "As You Were! Ex-Cadets Remember". In 2 Volumes. Volume I: 1876-1918. Volume II: 1919-1984. Royal Military College. [Kingston]. The R.M.C. Club of Canada. 1984

- Obituary

- Canadian Navy press release regarding his death

- Biography

- Legion of Honor award information

- Order of Canada citation

| Academic offices | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by Brigadier W.A.B. Anderson |

Commandant of the Royal Military College of Canada 1957–1960 |

Succeeded by Air Commodore Douglas Bradshaw |