Debased heraldry

Debased heraldry is heraldry containing complex, non-standard and non-heraldic charges. They cannot be correctly drawn from the blazon alone, as is the case with the purest form of heraldry. Most debased heraldry was created after the 17th century, and in general early heraldry dating from the start of the heraldic era (c.1200-1215), deemed the purest and best, utilises simple and standard charges. However some early heraldry was debased, for example the arms of the Bishop of Chichester, overly complex in nature. The original purpose of heraldry was for a knight to identify himself clearly by a unique and clear design on his shield. Debased heraldry treats the shield rather as a canvas for the display of complex art work. The small space available on a shield is thus not ideally suited to this function.

George Thomas Clark (1809-1898) wrote as follows on the subject in his well-regarded article on heraldry in the Encyclopaedia Britannica (9th & 10th editions):[1]

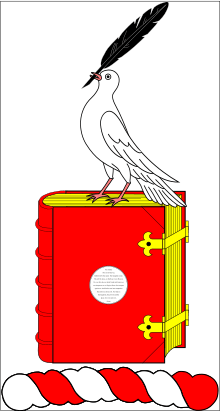

- "Of debased heraldry there is no lack of examples, and a few are ancient. Thomas de Insula (Thomas de Lisle (c.1298–1361)), Bishop of Ely (1345-61), bore Gules, three bezants, on each a crowned king, robed sable, doubled ermine, sustaining a covered cup in his right hand and a sword in his left, both or. No doubt, like the arms of the Sees of Chichester and Salisbury, this extraordinary coat was meant to be painted on a banner. Camden (1551-1623) granted a great number of coats, mostly of a complex character, and since his time heraldic taste has not improved. Tetlow (granted 1760 (of Houghton, Manchester, Lancashire[2][3]) bore (as crest): On a book erect gules, clasped and leaved or, a silver penny argent, thereon written the Lord’s Prayer; at the top of the book a dove proper, in his beak a crowquill pen sable. Other grants show negroes working in a plantation, Chinese porters carrying cinnamon, etc. The grants to Lord Nelson (d.1805) and his gallant captains, and to the elder Herschel (William Herschel (1738-1822)), are utterly unheraldic. It can scarcely be wondered at that Lord Chesterfield (Philip Stanhope, 4th Earl of Chesterfield (1694-1773)), correcting the Garter of his day, remarked, "You foolish man, you don’t understand your own foolish business."