Deadlock

In concurrent computing, a deadlock is a state in which each member of a group is waiting for another member, including itself, to take action, such as sending a message or more commonly releasing a lock.[1] Deadlock is a common problem in multiprocessing systems, parallel computing, and distributed systems, where software and hardware locks are used to arbitrate shared resources and implement process synchronization.[2]

In an operating system, a deadlock occurs when a process or thread enters a waiting state because a requested system resource is held by another waiting process, which in turn is waiting for another resource held by another waiting process. If a process is unable to change its state indefinitely because the resources requested by it are being used by another waiting process, then the system is said to be in a deadlock.[3]

In a communications system, deadlocks occur mainly due to lost or corrupt signals rather than resource contention.[4]

- A single process goes through.

- The later process has to wait.

- A deadlock occurs when the first process locks the first resource at the same time as the second process locks the second resource.

- The deadlock can be resolved by cancelling and restarting the first process.

Necessary conditions

A deadlock situation on a resource can arise if and only if all of the following conditions hold simultaneously in a system:[5]

- Mutual exclusion: At least one resource must be held in a non-shareable mode. Otherwise, the processes would not be prevented from using the resource when necessary. Only one process can use the resource at any given instant of time.[6]

- Hold and wait or resource holding: a process is currently holding at least one resource and requesting additional resources which are being held by other processes.

- No preemption: a resource can be released only voluntarily by the process holding it.

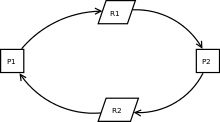

- Circular wait: each process must be waiting for a resource which is being held by another process, which in turn is waiting for the first process to release the resource. In general, there is a set of waiting processes, P = {P1, P2, …, PN}, such that P1 is waiting for a resource held by P2, P2 is waiting for a resource held by P3 and so on until PN is waiting for a resource held by P1.[3][7]

These four conditions are known as the Coffman conditions from their first description in a 1971 article by Edward G. Coffman, Jr.[7]

While these conditions are sufficient to produce a deadlock on single-instance resource systems, they only indicate the possibility of deadlock on systems having multiple instances of resources.[8]

Deadlock handling

Most current operating systems cannot prevent deadlocks.[9] When a deadlock occurs, different operating systems respond to them in different non-standard manners. Most approaches work by preventing one of the four Coffman conditions from occurring, especially the fourth one.[10] Major approaches are as follows.

Ignoring deadlock

In this approach, it is assumed that a deadlock will never occur. This is also an application of the Ostrich algorithm.[10][11] This approach was initially used by MINIX and UNIX.[7] This is used when the time intervals between occurrences of deadlocks are large and the data loss incurred each time is tolerable.

Detection

Under the deadlock detection, deadlocks are allowed to occur. Then the state of the system is examined to detect that a deadlock has occurred and subsequently it is corrected. An algorithm is employed that tracks resource allocation and process states, it rolls back and restarts one or more of the processes in order to remove the detected deadlock. Detecting a deadlock that has already occurred is easily possible since the resources that each process has locked and/or currently requested are known to the resource scheduler of the operating system.[11]

After a deadlock is detected, it can be corrected by using one of the following methods:

- Process termination: one or more processes involved in the deadlock may be aborted. One could choose to abort all competing processes involved in the deadlock. This ensures that deadlock is resolved with certainty and speed. But the expense is high as partial computations will be lost. Or, one could choose to abort one process at a time until the deadlock is resolved. This approach has high overhead because after each abort an algorithm must determine whether the system is still in deadlock. Several factors must be considered while choosing a candidate for termination, such as priority and age of the process.

- Resource preemption: resources allocated to various processes may be successively preempted and allocated to other processes until the deadlock is broken.[12]

Prevention

Deadlock prevention works by preventing one of the four Coffman conditions from occurring.

- Removing the mutual exclusion condition means that no process will have exclusive access to a resource. This proves impossible for resources that cannot be spooled. But even with spooled resources, the deadlock could still occur. Algorithms that avoid mutual exclusion are called non-blocking synchronization algorithms.

- The hold and wait or resource holding conditions may be removed by requiring processes to request all the resources they will need before starting up (or before embarking upon a particular set of operations). This advance knowledge is frequently difficult to satisfy and, in any case, is an inefficient use of resources. Another way is to require processes to request resources only when it has none; First they must release all their currently held resources before requesting all the resources they will need from scratch. This too is often impractical. It is so because resources may be allocated and remain unused for long periods. Also, a process requiring a popular resource may have to wait indefinitely, as such a resource may always be allocated to some process, resulting in resource starvation.[13] (These algorithms, such as serializing tokens, are known as the all-or-none algorithms.)

- The no preemption condition may also be difficult or impossible to avoid as a process has to be able to have a resource for a certain amount of time, or the processing outcome may be inconsistent or thrashing may occur. However, the inability to enforce preemption may interfere with a priority algorithm. Preemption of a "locked out" resource generally implies a rollback, and is to be avoided since it is very costly in overhead. Algorithms that allow preemption include lock-free and wait-free algorithms and optimistic concurrency control. If a process holding some resources and requests for some another resource(s) that cannot be immediately allocated to it, the condition may be removed by releasing all the currently being held resources of that process.

- The final condition is the circular wait condition. Approaches that avoid circular waits include disabling interrupts during critical sections and using a hierarchy to determine a partial ordering of resources. If no obvious hierarchy exists, even the memory address of resources has been used to determine ordering and resources are requested in the increasing order of the enumeration.[3] Dijkstra's solution can also be used.

Livelock

A livelock is similar to a deadlock, except that the states of the processes involved in the livelock constantly change with regard to one another, none progressing.

The term was coined by Edward A. Ashcroft in a 1975 paper[14] in connection with an examination of airline booking systems.[15] Livelock is a special case of resource starvation; the general definition only states that a specific process is not progressing.[16]

Livelock is a risk with some algorithms that detect and recover from deadlock. If more than one process takes action, the deadlock detection algorithm can be repeatedly triggered. This can be avoided by ensuring that only one process (chosen arbitrarily or by priority) takes action.[17]

Distributed deadlock

Distributed deadlocks can occur in distributed systems when distributed transactions or concurrency control is being used.

Distributed deadlocks can be detected either by constructing a global wait-for graph from local wait-for graphs at a deadlock detector or by a distributed algorithm like edge chasing.

Phantom deadlocks are deadlocks that are falsely detected in a distributed system due to system internal delays but do not actually exist.

For example, if a process releases a resource R1 and issues a request for R2, and the first message is lost or delayed, a coordinator (detector of deadlocks) could falsely conclude a deadlock (if the request for R2 while having R1 would cause a deadlock).

See also

- Aporia

- Banker's algorithm

- Catch-22 (logic)

- Circular reference

- Dining philosophers problem

- File locking

- Gridlock (in vehicular traffic)

- Hang (computing)

- Impasse

- Infinite loop

- Linearizability

- Model checker can be used to formally verify that a system will never enter a deadlock

- Ostrich algorithm

- Priority inversion

- Race condition

- Readers-writer lock

- Sleeping barber problem

- Stalemate

- Synchronization (computer science)

- Turn restriction routing

References

- Coulouris, George (2012). Distributed Systems Concepts and Design. Pearson. p. 716. ISBN 978-0-273-76059-7.

- Padua, David (2011). Encyclopedia of Parallel Computing. Springer. p. 524. ISBN 9780387097657. Retrieved 28 January 2012.

- Silberschatz, Abraham (2006). Operating System Principles (7th ed.). Wiley-India. p. 237. ISBN 9788126509621. Retrieved 29 January 2012.

- Schneider, G. Michael (2009). Invitation to Computer Science. Cengage Learning. p. 271. ISBN 978-0324788594. Retrieved 28 January 2012.

- Silberschatz, Abraham (2006). Operating System Principles (7 ed.). Wiley-India. p. 239. ISBN 9788126509621. Retrieved 29 January 2012.

- "ECS 150 Spring 1999: Four Necessary and Sufficient Conditions for Deadlock". nob.cs.ucdavis.edu. Archived from the original on 29 April 2018. Retrieved 29 April 2018.

- Shibu, K. (2009). Intro To Embedded Systems (1st ed.). Tata McGraw-Hill Education. p. 446. ISBN 9780070145894. Retrieved 28 January 2012.

- "Operating Systems: Deadlocks". www.cs.uic.edu. Retrieved 25 April 2020.

If a resource category contains more than one instance, then the presence of a cycle in the resource-allocation graph indicates the possibility of a deadlock, but does not guarantee one. Consider, for example, Figures 7.3 and 7.4 below:

- Silberschatz, Abraham (2006). Operating System Principles (7 ed.). Wiley-India. p. 237. ISBN 9788126509621. Retrieved 29 January 2012.

- Stuart, Brian L. (2008). Principles of operating systems (1st ed.). Cengage Learning. p. 446. ISBN 9781418837693. Retrieved 28 January 2012.

- Tanenbaum, Andrew S. (1995). Distributed Operating Systems (1st ed.). Pearson Education. p. 117. ISBN 9788177581799. Retrieved 28 January 2012.

- "IBM Knowledge Center". www.ibm.com. Archived from the original on 19 March 2017. Retrieved 29 April 2018.

- Silberschatz, Abraham (2006). Operating System Principles (7 ed.). Wiley-India. p. 244. ISBN 9788126509621. Retrieved 29 January 2012.

- Ashcroft, E.A. (1975). "Proving assertions about parallel programs". Journal of Computer and System Sciences. 10: 110–135. doi:10.1016/S0022-0000(75)80018-3.

- Kwong, Y. S. (1979). "On the absence of livelocks in parallel programs". Semantics of Concurrent Computation. Lecture Notes in Computer Science. 70. pp. 172–190. doi:10.1007/BFb0022469. ISBN 3-540-09511-X.

- Anderson, James H.; Yong-jik Kim (2001). "Shared-memory mutual exclusion: Major research trends since 1986". Archived from the original on 25 May 2006.

- Zöbel, Dieter (October 1983). "The Deadlock problem: a classifying bibliography". ACM SIGOPS Operating Systems Review. 17 (4): 6–15. doi:10.1145/850752.850753. ISSN 0163-5980.

Further reading

- Kaveh, Nima; Emmerich, Wolfgang. "Deadlock Detection in Distributed Object Systems" (PDF). London: University College London. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Bensalem, Saddek; Fernandez, Jean-Claude; Havelund, Klaus; Mounier, Laurent (2006). Confirmation of deadlock potentials detected by runtime analysis. Proceedings of the 2006 Workshop on Parallel and Distributed Systems: Testing and Debugging. ACM. pp. 41–50. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.431.3757. doi:10.1145/1147403.1147412. ISBN 978-1595934147.

- Coffman, Edward G., Jr.; Elphick, Michael J.; Shoshani, Arie (1971). "System Deadlocks" (PDF). ACM Computing Surveys. 3 (2): 67–78. doi:10.1145/356586.356588.

- Mogul, Jeffrey C.; Ramakrishnan, K. K. (1997). "Eliminating receive livelock in an interrupt-driven kernel". ACM Transactions on Computer Systems. 15 (3): 217–252. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.156.667. doi:10.1145/263326.263335. ISSN 0734-2071.

- Havender, James W. (1968). "Avoiding deadlock in multitasking systems". IBM Systems Journal. 7 (2): 74. doi:10.1147/sj.72.0074.

- Holliday, JoAnne L.; El Abbadi, Amr. "Distributed Deadlock Detection". Encyclopedia of Distributed Computing. Archived from the original on 2 November 2015. Retrieved 29 December 2004.

- Knapp, Edgar (1987). "Deadlock detection in distributed databases". ACM Computing Surveys. 19 (4): 303–328. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.137.6874. doi:10.1145/45075.46163. ISSN 0360-0300.

- Ling, Yibei; Chen, Shigang; Chiang, Jason (2006). "On Optimal Deadlock Detection Scheduling". IEEE Transactions on Computers. 55 (9): 1178–1187. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.259.4311. doi:10.1109/tc.2006.151.

External links

- "Advanced Synchronization in Java Threads" by Scott Oaks and Henry Wong

- Deadlock Detection Agents

- DeadLock at the Portland Pattern Repository

- Etymology of "Deadlock"