Day of the Oprichnik

Day of the Oprichnik (Russian: День опричника, Den' oprichnika) is a 2006 novel by the Russian writer Vladimir Sorokin. The narrative is set in the near future, when the Tsardom of Russia has been restored, and follows a government henchman, an oprichnik, through a day of grotesque events. Sorokin in one of the later interviews[1] confessed that he did not anticipate his novel be an accurate picture of the future, even in some subtle details, but rather wrote this book as a warning and "mystical precaution" against the state of events described in the storyline. The title is a reference to the Oprichnina, the black-clad secret police of Ivan the Terrible, whose symbol were a black dog's head (to sniff out treason) and a broom (to sweep away all traitors) .

First edition | |

| Author | Vladimir Sorokin |

|---|---|

| Original title | День опричника Den' oprichnika |

| Translator | Jamey Gambrell |

| Country | Russia |

| Language | Russian |

| Publisher | Zakharov Books |

Publication date | 2006 |

Published in English | 2010 |

| Pages | 224 |

| ISBN | 5-8159-0625-5 |

Plot summary

The novel begins with protagonist Andrei Komiaga dreaming of a white stallion, a recurrent symbol of freedom that progressively slips away from the Oprichnik (the real Oprichinks of the 16th century always rode black horses). The neo-medieval enforcer's morning sees him murder a boyer (nobleman) and join in the gang-rape of his wife, a task he justifies to himself as important work. From there Komiaga conducts other seemingly routine activities: he investigates an artist penning inflammatory poetry about the Tsarina, visits a book-burning clairvoyant, ingests a fish that lays hallucinogenic eggs in his brain, and finally participates in a ritualistic group sex and self-torture with his fellow Oprichniki. The day ends with a demented Komiaga returning home, only to find that the white stallion of his dreams has retreated further from his grasp. As the white stallion runs away, Komiage cries out "My white stallion, wait! Don’t run away...where are you going?"[2]

Reception

From the New York Times Book Review: "Sorokin's pyrotechnics are often craftily twinned with Soviet-era references and conventions. The title and 24-hour frame of Day of the Oprichnik bring to mind Solzhenitsyn's One Day in the Life of Ivan Denisovich (1962), an exposé of a Gulag camp that depicts an Everyman-victim who finds dignity in labor, almost like a Socialist Realist hero. But whereas Solzhenitsyn's masterpiece unintentionally demonstrated the deep impact that Soviet tropes had on its author, Sorokin's comic turn deliberately shows how Soviet and even Old Muscovy mentalities persist."[3] Victoria Nelson in her review wrote: "It’s an outrageous, salacious, over-the-top tragicomic depiction of an utterly depraved social order whose absolute monarch (referred to only as “His Majesty”) is a blatant conflation of the country’s current president with its ferocious 16th-century absolute monarch known as Ivan Grozny."[4]

Analysis

The title of the book is a reference to the 1962 novel One Day in the Life of Ivan Denisovich by Alexander Solzhenitsyn.[5] Sorokin has been vocal in expressing his dislike of not only Solzhenitsyn as a man, but also his writing style and his right-wing politics, so the reference is unlikely to be understood as a favorable tribute.[5] However, most of the novel is a parody of the 1927 novel Za chertopolokhom (Behind the Thistle) by General Pyotr Krasnov, the former ataman of the Don Cossack Host who went into exile in 1919.[6] Krasnov's novel, which is published in Russian in Paris, which was almost completely unknown in Russia until 2002 when it was published in Moscow and has became quite popular, being in its third reprinting as of 2009.[7] Behind the Thistle is a future history, depicting Russia in the 1990s being ruled by a restored monarchy that has severed all contact with the West, which is precisely the same scenario as Day of the Oprichnik (which is set in 2028), but only Sorokin has inverted the premise.[6] The Russia of the future depicted in the Day of the Oprichnik is as dystopian as Krasnov's Russia of the future is utopian.[8]

As in Behind the Thistle, the Russia of Day of the Oprichnik is ruled over by a restored monarchy which came about as a result of an apocalyptic disaster that killed millions.[9] In Behind the Thistle, Krasnov described in detail an unsuccessful Soviet invasion of Poland and Romania that led to vast qualities of deadly chemical gases being released which kill millions at the beginning of the novel; by contrast Sorokin is a rather vaguer about the nature of the disaster, which is described in his novel only as the "Grey Turmoil".[10] The term "Grey Turmoil" is a reference to the "Red Turmoil" of 1917 and the "White Turmoil" of 1991.[5] As in Behind the Thistle, the social order in Day of the Oprichnik is upheld by daily public floggings, torture and executions of Russians who dare to think differently and Russia has very close relations with China.[6] The Tsar in the novel resembles Ivan the Terrible in terms of both appearance and personality, and like the real Ivan has a stern, patriarchal leadership style, portraying himself the father of the nation and his subjects as his "children" in need of his strict supervision.[7] Much like Ivan the Terrible, the Tsar in Day of the Oprichnik insists obsessively on "chastity and cleanliness" from his subjects. [4] As in Krasnov's novel, the Russian characters dress in traditional costumes; the men grow the traditional long breads while the women braid their hair; and all of the characters speak in a pseudo-folksy way meant to evoke the Russian of the 16th and 17th centuries.[11] Alongside the intentionally anachronistic Russian, the language of Day of the Oprichnik includes much slang from the vory v zakone ("thieves in law", i.e Russian organised crime, which forms a very distinctive subculture in Russia complete with its own dialect of Russian) and New Russian slang of 1990s-2000s, making for a Russian that sounds both very modern and jarringly anachronistic.[11] In the novel, a house is called a terem, a mobile phone is a mobilov and a car is called a merin (mule).[11] The ringtone for the phones of the orichniks is the cracking of a whip.[11] Marijuana has been legalised in this Russia it "does no harm to a simple person, but helps him relax".[11]

The subculture of the vory v zakone who despite their name engage in all sorts of criminal activity is characterized by its own dialect and its own rules. For an example, a vor (thief) must never willingly serve in the military; must never a report a crime, even against themselves; and must never testify against another vor, even if he is a rival. The most notable distinguishing marks of the vory are that their bodies are covered with elaborate tattoos full of symbolism about their status within the vory v zakone and that they always wear Orthodox crucifixes around their necks. As the vory have a well deserved reputation for being brutal, amoral and predatory criminals, their dialect of Russian has a very low status in Russia, and to speak the dialect of the vory is just as much a mark of criminality as to have one's bodies covered with their tattoos. The fact that the Oprichniki in the novel, who despite their self-proclaimed status as the guardians of the state and society use words and phrases from the dialect of the vory is meant to be ironical and comic.[11]

Like in Behind the Thistle, a gigantic wall has been built to sever all contact with the West while Russia under the restored monarchy uses advanced technology.[11] Echoing the Great Wall of China, the wall is called the Great Wall of Russia."[2] The narrator tell the reader in his breathless prose that the Great Wall was necessary to: "cut us off from stench and unbelievers, from the damned, cyberpunks, from sodomites, Catholics, melancholiacs, from Buddhists, sadists, Satanists, and Marxists; from megamasturbators, fascists, pluralists, and atheists!"[4] In the Day of the Oprichnik, an enormous super-highway has been built to link Russia to China, and Chinese cultural influence is very strong with paintings of Chinese dragons commonly been seen on the walls of homes alongside Orthodox icons and, most people eat Chinese food using chopsticks alongside traditional Russian food.[11] The principle revenue for the Russian state is taxing the Chinese businessmen who sent their products on vast convoys of trucks to Europe via the highway.[12] Everything that is used in Russia is manufactured in China leading characters to bemoan "We make children on Chinese beds!" and "We do our business on Chinese toilets!"[2] Unlike Behind the Thistle where Russia and China are equal partners in an alliance to uphold Asian values, it is strongly implied in Day of the Oprichnik that Russia and China are not equals with the more wealthier and powerful Chinese being the senior partners and Russians the junior partners in their alliance.[11]

The Russia of Day of the Oprichnik seems to be in the Chinese sphere of influence, and it is hinted that it is the leaders in Beijing who dictate to the leaders in Moscow as it stated that all of the weapons used by the Russian Army are made in China.[12] At one point, the Oprichniki when talking to their commander whom they call Batia (Daddy) ask him: "How much more longer does our great Russia have to kowtow before China?"[13] The Tsar of Day of the Oprichnik is presented as all-powerful to his subjects, but he may in fact be a mere puppet leader. Through the narrator portrays the Russia of the novel as the world's greatest power, he also complains that "the Chinese are expanding their population in Krasnoryarsk and Novosibirsk".[13] The Tsar distracts attention of the Oprichniki from their fears of Chinese domination by encouraging them to engage in more violence against their fellow Russians.[13] The Russian literature scholar Tatiana Filimonova has accused Sorokin of engaging in this novel together with all his other books in the fear of the "Yellow Peril", noting in a recurring theme of all his novels is the image of China as an expansionist and economically dominating power that will subject Russia to its will and as the Chinese as a soulless, materialistic people devoid of any positive qualities whose only interest is sheer greed.[14] However, Sorokin's target are as much Russia's institutions as China, which he portrays as fostering a stifling conservatism that crushes intellectual innovation and criticism, leading to a stagnant and declining Russia that inevitably falls into the Chinese sphere of influence.[15] Sorokin's heroes tend to be humanist intellectuals who have to struggle against both corrupt, petty and mean-spirited bureaucrats who are temperamentally opposed to any change and the apathy, ignorance and philistinism of the Russian masses.[16]

As in Behind the Thistle, the Russia of Day of the Oprichnik is technologically advanced.[11] In the novel, gigantic underground high-speed trains link every city in Russia and everything has been computerized.[11] Every home has a Jacuzzi whose walls are decorated with Russian folk art.[11] In imitation of the skater-samorbranka of Russian folklore, when patrons order food in their restaurants, the food emerges from inside of the tables.[11] Homes have high-tech, computer-controlled fridges and stoves while the people anachronistically cook their food in medieval clay pots.[11] But since the technology is all Chinese, it is not due to the Russian state. The Oprichniki drive cars with heads of dogs impaled on the hoods alongside brooms, the symbols of the Oprichnina of Ivan the Terrible.[11] Just as was the case with the real Oprichnina, the Oprichniki drink heavily and toast the Tsar and the Orthodox Church while engaging in extreme sadistic violence that is the complete antithesis of the Christian values that they profess to uphold.[4] The American critic Victoria Nelson noted in her review:"In a pitch-perfect channeling of the fascist temperament, the voice [of the narrator] proudly sharing these brutal exploits radiates a naïve and sentimental piety ruthlessly undercut by vicious sadism and self-regarding cunning. Bursting with near-hysterical enthusiasm, the latter-day Oprichnik crosses himself and invokes the Holy Church as he righteously inflicts sickening violence on His Majesty’s identified enemies".[4] Likewise, the Oprichniki of the novel profess to be the ultra-patriotic defenders of traditional Russian culture, but much of their work consists in burning the classics of Russian literature.[2] The Oprichniki have long breads, wear traditional caftans, but carry around laser guns.[2]

In Behind the Thistle, people have burned their internal passports to show that now free under the Tsar while in Day of the Opricnnik people have burned their foreign passports to show that are now free from foreign influence.[17] In Krasnov's book the "Jewish Question" has been solved as "they [the Jews] no longer have the power to rule over us nor can they hide under false Russian names to infiltrate the government".[17] Likewise in Sorokin's novel, the "Jewish Question" has been solved as: "All this lasted and putrefied until the Tsar's degree-accordingly to which non-baptized citizens of Russia should not have Russian names, but names in accordance with their nationality. Thus our wise Tsar finally solved the Jewish question in Russia. He took the smart Jews under his wing-and the stupid ones just scattered".[17] In both the novels of Krasnov and Sorokin, every home has a television that only broadcasts the Tsar's daily speech to his subjects.[17] In both books, people watch patriotic plays at the theater, dance to the traditional music of the balalaika, listen to singers who sing only folk songs, and read newspapers beautifully printed in the ornate Russian of the 16th century, which have no editorials about any issue.[17]

Both books are concerned with violence as necessary to maintain the social order.[18] Whereas extreme violence in Behind the Thistle is glorified as the only way to keep the social order functioning, the extreme violence in Day of Orichnik is presented as repulsive and sickening.[19] In Krasnov's book, extreme violence committed by the state is a means to an end, namely to maintain the social order, but in Sorokin's book, extreme violence by the state has a psycho-sexual purpose and is presented as a religious duty.[19] In Sorokin's book, violence has become a cultural ritual and forms an integral part of how society functions.[19] In Sorokin's world, gratuitous and sadistic violence is a normal part of social interactions, and throughout his book violence is presented in a language that links the violence to both sex and religion.[19] Krasnov noted that in Asian societies, it is the collective that takes precedence over the individual, and for this reason argued that Russia was an Asian as opposed to a European nation. Likewise, in Sorokin's book, everything is done collectively.[19] Through the Oprichniki help themselves to the property belonging to their victims, this is always justified under the grounds that it is good for the state.[2] The way in which the Oprichniki pursue their own interests while constantly mouthing the language of Russian patriotism to justify their misdeeds satirizes the siloviki, the former secret police officials who enjoy much power and prestige in the Russia of Vladimir Putin, engaging in gross corruption while mouthing ultra-patriotic language that they all merely serving the state, and that what is good for the Russian state is always good for Russia.[2] The Tsar, whom the narrator always refers to as "His Majesty", appears as a shining hologram dispensing vapid and asinine remarks, which the narrator insists represent the most profound and deep wisdom as he states with great conviction: “His Majesty sees everything, hears everything. He knows who needs what".[4]

In Day of the Oprichnik, both sex and violence are always done collectively.[19] The purpose of the Oprichniki in the novel is to annihilate any notion of individualism and to promote the reestablishment of "we" as the basis of thinking rather than "I".[20] Thus, the gang-rape of a woman whose only crime was to be the wife of a free-thinking boyar is justified by the narrator, Andrei Komyaga, under the grounds that it was done to promote a collective identity for all the Oprichniki as it is the wish of all Oprichniki to be united together into one collective mind devoid of any sort of individuality or identity.[20] In the novel, gang-rapes are "standard procedure" for the Oprichniki.[20] Towards the end of the day, the Oprichniki all sodomized one another, forming vast "human caterpillars" as thousands of men have sex with one another as part of the effort to form a collective identity.[20] After the orgy, the Oprichniki mutilate one another as they take turns drilling screws through their legs, a process of self-mutilation done again to form a collective identity.[20]

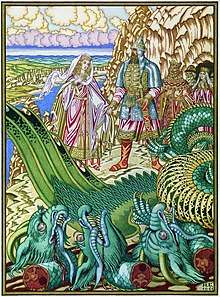

In Krasnov's novel, a recurring themes is a dream that occurs in the mind of the hero where he sees a beautiful girl threatened by the zmei gorynych, the monstrous three-headed dragon of Russian mythology.[21] In Behind the Thistle, the girl symbolizes Russia and the zmei gorynych symbolizes the West.[21] In Sorokin's novel, Komyaga the narrator, under the influence of hallucinogenic drugs imagines himself and all of the other Oprichniki merging their bodies together to turn into a zmei gorynych.[21] The zmei gorynych then flies across the Atlantic Ocean to destroy the United States, the land of individualism and freedom.[21] The zmei gorynych proceeds to rape and kill an American woman, who symbolizes liberty and individualism, marking the triumph of the Asian collectivism over the Western individualism, the Russian "we" over the American "I".[22] Afterwards, Komyaga learns his other Oprichniki all had the same vision, showing their minds are all being merged into one collective entity.[21] Komyaga relates his demented, drug-fueled vision as an incantatory chant, using the style of a pseudo-medieval poem, which makes his vision sound both antiquated and blasphemous.[21] In this way, Sorokin inverts the key symbolism of Krasnov's book, turning Russia into the male zmei gorynych and the innocent girl becomes the West.[22] The sort of power that is depicted in Day of the Oprichnik is a specifically a masculine power as the Oprichnina is presented as all male "brotherhood" and the language that is evoked to describe power is a masculine language.[22] Women appear in Day of the Oprichnik only as rape victims, entertainers or sex objects as the unpopular czarina becomes popular because of her "mesmerizing" breasts.[2]

Much of Day of the Oprichnik is influenced by the theories of the Russian literary thinker Mikhail Bakhtin who argued in his 1965 book Rabelais and His World about François Rabelais that the image of the collective grotesque body symbolizing a group is created in such a way that one part of the body is formed by death of another.[20] Taking up Bakhtin's theory, Sorokin has his narrator Komyaga present the gang-rape of the unfortunate wife as a sort of death for her as an individual, but a sort of collective birth for the Oprichniki who by all violating the same body became part of the same process and identity.[20] What is for the woman an act of individual pain and agony becomes a collective celebration of life for the Oprichniki.[20] Bakhtin argued in Rabelais and His World that "the true existence of an object is its steamy side" and thus a "destroyed object does not completely destroy from reality, but rather obtains a new form of temporal and spatial existence" as a "destroyed object reappears in a new reality".[22] Bakhtin argued the destruction of an object in the medieval carnivals of France created a "cosmic hole" that allowed a new object to take its place while continuing the role of the former object.[22] Influenced by Bakhtin's argument, the destruction of America that Komyaga imagines is an effort to convert America from "anti-existence" to "existence" by creating a "hole" which allows the "good" Russia to replace the "evil" America as the world's greatest power.[23] In medieval Russian poetry known as the bylina, the hero was usually a bogatyr (knight) who had to go a quest for a tsar or princess; echoes of this tradition were found in the Socialist Realist Soviet literature, which usually featured a worker hero who like the bogatyr had to perform a mission that was much like a quest for Communism.[18] Much of the style of the book is a satire of the Socialist Realist style as Komyaga has to perform a quest of sorts to uphold the power of the state and annihilate his own identity over the course of a 24 hour period.[19] Through Komyaga is successful in his quest, his success is also his failure as the white stallion that symbolizes freedom is more farther away from him at the end of the novel than it was at the beginning of the novel

See also

Reviews

- Aptekman, Marina (Summer 2009). "Forward to the Past Or Two Radical Views on the Russian Nationalist Future: Pyotr Krasnov's Behind the Thistle and Vladimir Sorokin's Day of the Oprichnik". The Slavic and East European Journal. 53 (2): 241–260.

- Filimonova, Tatiana (January 2014). "Chinese Russia: Imperial Consciousness in Vladimir Sorokin's Writing". Region. 3 (2): 219–244.

References

- Alexandrov, Nikolay (15 November 2012). "Владимир Сорокин: «Гротеск стал нашим главным воздухом»" [Vladimir Sorokin: "The grotesque has become our main air"]. Colta.ru (in Russian). Retrieved 11 April 2020.

- Kotkin, Stephen (11 March 2011). "A Dystopian Tale of Russia's Future". New York Times. Retrieved 24 July 2020.

- Kotkin, Stephen (11 March 2011). "A Dystopian Tale of Russia's Future". The New York Times Book Review. Retrieved 11 April 2020.

- Nelson, Victoria (16 February 2019). "His Majesty: On Vladimir Sorokin's "Day of the Oprichnik"". Los Angeles Review of Books. Retrieved 25 July 2020.

- Aptekman 2009, p. 248.

- Aptekman 2009, p. 249-250.

- Aptekman 2009, p. 242.

- Aptekman 2009, p. 241-242.

- Aptekman 2009, p. 247-249.

- Aptekman 2009, p. 247-248.

- Aptekman 2009, p. 250.

- Filimonova 2014, p. 232.

- Filimonova 2014, p. 233.

- Filimonova 2014, p. 243.

- Filimonova 2014, p. 238-240.

- Filimonova 2014, p. 238.

- Aptekman 2009, p. 251.

- Aptekman 2009, p. 251-252.

- Aptekman 2009, p. 252.

- Aptekman 2009, p. 253.

- Aptekman 2009, p. 254.

- Aptekman 2009, p. 255.

- Aptekman 2009, p. 255-256.