Das zerbrochene Ringlein

"Das zerbrochene Ringlein" (The broken little ring) is a poem by Joseph von Eichendorff, which can be found also titled as Lied (lay, or song), first published 1813 by Justinus Kerner et al. in the almanac Deutscher Dichterwald (German Poets’ Forest) under the pseudonym "Florens" and afterwords in his novel Aus dem Leben eines Taugenichts.[1] 1807/08 Eichendorff pondered in his diaries about his unhappy love affair with Käthchen Förster, the daughter of a Heidelberg cellarman, during his student days.[2] This fact is remembered by a memorial stone at the Philosophenweg (Philosophers' Walk) in Heidelberg, along the Neckar.

| by Joseph von Eichendorff | |

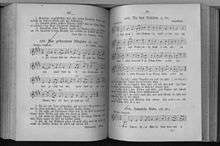

The poem as a song in Allgemeines Deutsches Kommersbuch, Lahr, 1896 | |

| First published in | 1813 |

|---|---|

| Language | German |

| Subject(s) | unhappy love |

| Rhyme scheme | abab |

| Publisher | Justinus Kerner |

| Lines | 20 |

In 1814, Eichendorf's love poem was set to music by Friedrich Glück,[3] and became popular under the title "In einem kühlen Grunde" (In a cool valley), taken from the first verse of the first stanza. The poem can be heard in recent versions by Comedian Harmonists, Heino, and Max Raabe, among others.[4]

Text

Das zerbrochene Ringlein

|

The Broken Ring

|

External links

- In einem kühlen Grunde, sung by Franz Porten, Columbia Hartguss-Wachswalze #50264, ca. 1905.

- In einem kühlen Grunde sung by the Comedian Harmonists

References

- Joseph von Eichendorff: Aus dem Leben eines Taugenichts (Memoirs of a good-for-nothing), Vereinsbuchhandlung, Berlin 1826, p. 227. http://images.google.de/imgres?imgurl=https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/f/f3/Aus_dem_Leben_eines_Taugenichts_und_das_Marmorbild.djvu/page231-1260px-Aus_dem_Leben_eines_Taugenichts_und_das_Marmorbild.djvu.jpg&imgrefurl=https://de.wikisource.org/wiki/Seite:Aus_dem_Leben_eines_Taugenichts_und_das_Marmorbild.djvu/231&h=2149&w=1260&tbnid=f_V8BBCi1W7HPM:&docid=fft9F56IqhU1cM&itg=1&ei=NLpRVqCJC4amsAGh06fwAg&tbm=isch&iact=rc&uact=3&page=1&start=0&ved=0ahUKEwig8_r7iKTJAhUGEywKHaHpCS4QrQMIbzAZ

- Cf. Günther Schiwy: Eichendorf. Der Dichter in seiner Zeit. Eine Biographie. Verlag C.H. Beck, München 2000, pp. 243-249. ISBN 3-406-46673-7

- Friedrich Glück#Bekannte Werke

- Interpretationen unter dem Titel „Die Klage“

- Translated by Geoffrey Herbert Chase. In: German Poetry from 1750 to 1900. Ed. by Robert M. Browning. The German Library, vol. 39. General ed. Volkmar Sander. The Continuum Publishing Company, New York 1984, p. 146-147.