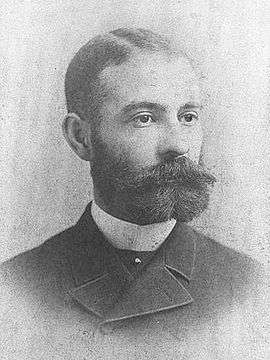

Daniel Hale Williams

Daniel Hale Williams (January 18, 1856[1] – August 4, 1931) was an American general surgeon, who in 1893 performed the first documented, successful pericardium surgery in the United States to repair a wound.[2][3][4][5] He founded Chicago's Provident Hospital, the first non-segregated hospital in the United States and also founded an associated nursing school for African Americans.

Daniel Hale Williams | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | January 18, 1856 |

| Died | August 4, 1931 (aged 75) |

| Alma mater | Chicago Medical College |

| Scientific career | |

| Fields | Cardiology |

| Institutions | Provident Hospital Meharry Medical College Freedman's Hospital St. Lukes Hospital Cook County Hospital |

The heart surgery at Provident, which his patient survived for the next twenty years, is referred to as "the first successful heart surgery" by Encyclopedia Britannica.[6][7] In 1913, Williams was elected as the only African-American charter member of the American College of Surgeons.[6]

Career

When Daniel Hale Williams graduated from what is today Northwestern University Medical School, he opened a private practice where his patients were white and black. Black doctors, however, were not allowed to work in American hospitals. As a result, in 1891, Williams founded the Provident Hospital and training school for nurses in Chicago. This was established mostly for the benefit of African-American residents, to increase their accessibility to health care, but its staff and patients were integrated from the start.[8]

In 1893, Williams became the first African American on record to have successfully performed pericardium surgery to repair a wound. On September 6, 1891,[3][4] Henry Dalton was the first American to successfully perform pericardium surgery to repair a wound. [9] Earlier successful surgeries to drain the pericardium, by performing a pericardiostomy were done by Francisco Romero in 1801[10] and Dominique Jean Larrey in 1810.[11]

On July 10, 1893, Williams repaired the torn pericardium of a knife wound patient, James Cornish.[3] Cornish, who was stabbed directly through the left fifth costal cartilage,[3] had been admitted the previous night. Williams decided to operate the next morning in response to continued bleeding, cough and "pronounced" symptoms of shock.[3] He performed this surgery, without the benefit of penicillin or blood transfusion, at Provident Hospital, Chicago.[12] It was not reported until 1897.[3] He undertook a second procedure to drain fluid. About fifty days after the initial procedure, Cornish left the hospital.[8]

In 1893, during the administration of President Grover Cleveland, Williams was appointed surgeon-in-chief of Freedman's Hospital in Washington, D.C., a post he held until 1898. That year he married Alice Johnson, who was born in the city and graduated from Howard University, and moved back to Chicago. In addition to organizing Provident Hospital, Williams also established a training school for African-American nurses at the facility. In 1897, he was appointed to the Illinois Department of Public Health, where he worked to raise medical and hospital standards.[13]

Williams was a Professor of Clinical Surgery at Meharry Medical College in Nashville, Tennessee, and was an attending surgeon at Cook County Hospital in Chicago. He worked to create more hospitals that admitted African Americans. In 1895 he co-founded the National Medical Association for African-American doctors, and in 1913 he became a charter member and the only African-American doctor in the American College of Surgeons. However, he died in relative obscurity. His retirement home was in Idlewild, Michigan, a black community.[14]:269

Personal life

Daniel Hale Williams was born in 1856 and raised in the city of Hollidaysburg, Pennsylvania. His father, Daniel Hale Williams Jr., was the son of a Scots-Irish woman and a Black barber.[15] His mother was African American and likely also mixed race.

The fifth child born, Williams lived with his parents, a brother and five sisters. His family eventually moved to Annapolis, Maryland. Shortly after when Williams was nine, his father died of tuberculosis.[16] Williams' mother realized she could not manage the entire family and sent some of the children to live with relatives. Williams was apprenticed to a shoemaker in Baltimore, Maryland but ran away to join his mother, who had moved to Rockford, Illinois. He later moved to Edgerton, Wisconsin, where he joined his sister and opened his own barber shop. After moving to nearby Janesville, Wisconsin, Williams became fascinated by the work of a local physician and decided to follow his path.

He began working as an apprentice to Dr. Henry W. Palmer, studying with him for two years. In 1880, Williams entered Chicago Medical College, now known as Northwestern University Medical School. After graduation from Northwestern in 1883, he opened his own medical office in Chicago, Illinois.[17]

Williams was married in 1898 to Alice Johnson, natural daughter of American sculptor Moses Jacob Ezekiel and a mixed-race maid.[18] Williams died of a stroke in Idlewild, Michigan on August 4, 1931. His wife, Alice Johnson, had died in 1924.[8]

Legacy

In the 1890s several attempts were made to improve cardiac surgery. On September 6, 1891 the first successful pericardial sac repair operation in the United States of America was performed by Henry C. Dalton of Saint Louis, Missouri.[19] The first successful surgery on the heart itself was performed by Norwegian surgeon Axel Cappelen on September 4, 1895 at Rikshospitalet in Kristiania, now Oslo.[20][21] The first successful surgery of the heart, performed without any complications, was by Dr. Ludwig Rehn of Frankfurt, Germany, who repaired a stab wound to the right ventricle on September 7, 1896.[22][23] Despite these improvements, heart-related surgery was not widely accepted in the field of medical science until during World War II. Surgeons were forced to improve their methods of surgery in order to repair severe war wounds.[24] Although they did not receive early recognition for their pioneering work, Dalton and Williams were later recognised for their roles in cardiac surgery.[24]

Honors

Williams received honorary degrees from Howard and Wilberforce Universities, was named a charter member of the American College of Surgeons, and was a member of the Chicago Surgical Society.

A Pennsylvania State Historical Marker was placed at U.S. Route 22 eastbound (Blair St., 300 block), Hollidaysburg, Pennsylvania, to commemorate his accomplishments and mark his boyhood home.[25]

Representation in other media

- The Stevie Wonder song "Black Man" honors the achievements of Williams, among others.

- Tim Reid Plays Dr. Williams in the TV series Sister, Sister season 5 episode 18 "I Have a Dream" (February 25, 1998).

- In 2002, scholar Molefi Kete Asante listed Daniel Hale Williams on his list of 100 Greatest African Americans.[26]

See also

References

- Although a half dozen biographical dictionaries place Daniel Hale Williams's birth date in 1858, 1856 is the date given in the U.S. Census records of Hollidaysburg, Pennsylvania, for 1860 and of Janesville, Wisconsin, for 1880; these agree on 1856, and the former was given by his parents. Also, when Dr. Dan Williams registered officially with the Illinois State Board of Health as a physician, on April 18, 1883, he gave his age as twenty-eight. This too points to 1856, making him at his registration twenty-seven years and three months old, or in his twenty-eighth year. Buckler, Helen. Daniel Hale Williams: Negro Surgeon, Pitman Publishing Company, 1954, pp. 287–288.

- Weisse, Allen B. (2011). "Cardiac Surgery: A Century of Progress". Texas Heart Institute Journal. 38 (5): 486–490. PMC 3231540. PMID 22163121.

- Shumacker, Harris B. (1992). The Evolution of Cardiac Surgery. Indiana University Press. p. 12. Retrieved May 12, 2007.

- Dalton, H. C. (1895). "III. Report of a Case of Stab-Wound of the Pericardium, Terminating in Recovery after Resection of a Rib and Suture of the Pericardium". Annals of Surgery. 21 (2): 147–152. doi:10.1097/00000658-189521060-00016. PMC 1494048. PMID 17860132.

- Organ, Claude. A Century of Black Surgeons, The U.S.A. Experience, Chapter 8, p. 311 Daniel Hale Williams, MD; Transcript Press, Norman OK, 1987 ISBN 0-9617380-0-6

- "Daniel Hale Williams American Physician". Encyclopedia Britannica. 2018.

- Encyclopædia Britannica (2008). "Reference Room: Daniel Hale Williams". African American World. PBS. Archived from the original on June 29, 2008. Retrieved November 26, 2008.

- "Daniel Hale Williams". The Black Inventor Online Museum. Archived from the original on March 31, 2009. Retrieved May 4, 2009.

- Wood, Horatio C. (1895). "American Medico-Surgical Bulletin". 8 (24). The Bulletin Publishing Company: 306. Retrieved August 29, 2013. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Aris A (September 1997). "Francisco Romero, the first heart surgeon". Ann. Thorac. Surg. 64: 870–1. doi:10.1016/s0003-4975(97)00760-1. PMID 9307502.

- Shumacker HB Jr. "When did cardiac surgery begin?". J Cardiovasc Surg (Torino). 30: 246–9. PMID 2651455.

- "History: Provident Hospital- The Provident Foundation". The Provident Foundation. 2008. Archived from the original on December 26, 2008. Retrieved November 22, 2008.

- "Who Was Dr. Daniel Hale Williams?". Jackson Heart Study Graduate Training and Education Center. Retrieved June 13, 2018.

- Buckler, Helen (1954). Doctor Dan : pioneer in American surgery. Boston: Little, Brown and Company. OCLC 964464.

- Bigelow (1992), p. 254

- "First Open Heart Surgeon". History: Dr. Daniel Hale Williams. Archived from the original on May 27, 2010. Retrieved May 23, 2010.

- "Daniel Hale Williams". The Black Inventor Online Museum. Archived from the original on August 18, 2013. Retrieved September 22, 2013.

- Washington, Booker Taliaferro (1907). Harlan, Louis R. (ed.). The Booker T. Washington Papers. vol.9: 1906-1908 (The Open Book ed.). Urbana: University of Illinois Press. p. 396. OCLC 58644475. Archived from the original on October 20, 2007.

- http://mail.blockyourid.com/~gbpprorg/invention/heartsurgery.html Archived September 26, 2015, at the Wayback Machine

- Westaby, Stephen; Bosher, Cecil. Landmarks in Cardiac Surgery. ISBN 1-899066-54-3.

- Baksaas ST, Solberg S (January 2003). "Verdens første hjerteoperasjon". Tidsskr Nor Lægeforen. 123 (2): 202–4.

- Absolon KB, Naficy MA (2002). First successful cardiac operation in a human, 1896: a documentation: the life, the times, and the work of Ludwig Rehn (1849–1930). Rockville, Maryland : Kabel, 2002

- Johnson SL (1970). History of Cardiac Surgery, 1896–1955. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins Press. p. 5.

- American Experience. "Timeline:Heart in History". PBS.com. Retrieved November 30, 2013.

- "Daniel Hale Williams - Pennsylvania Historical Markers on Waymarking.com". Waymarking.com. Retrieved November 15, 2014.

- Asante, Molefi Kete (2002). 100 Greatest African Americans: A Biographical Encyclopedia. Amherst, New York. Prometheus Books. ISBN 1-57392-963-8.

Bibliography

- Bigelow, Barbara Carlisle, Contemporary Black biography: profiles from the international Black community, Gale Research Inc., 1992, ISBN 0-8103-8554-6

Further reading

- Yenser, Thomas (1933). Who's Who in Colored America: 1930-1931-1932. Brooklyn: T. Yenser. OCLC 26073112.

- Buckler, Helen (1968). Daniel Hale Williams: Negro Surgeon. Originally published in 1954 as Doctor Dan: Pioneer in American Surgery. New York: Pitman. OCLC 220544784.

- Chenrow, Fred; Chenrow, Carol (1973). Reading Exercises in Black History, Volume 1. Elizabethtown, PA: The Continental Press, Inc. p. 60. ISBN 08454-2107-7