Daily Telegraph Affair

The Daily Telegraph Affair was the uproar that followed the 28 October 1908 publication in British newspaper The Daily Telegraph of comments by German Kaiser Wilhelm II intended to improve German–British relations. It was a major diplomatic blunder that worsened relations and badly hurt the Kaiser's reputation; after that he played a much smaller role in deciding foreign policy. The episode had a far greater impact in Germany than overseas.[1][2][3]

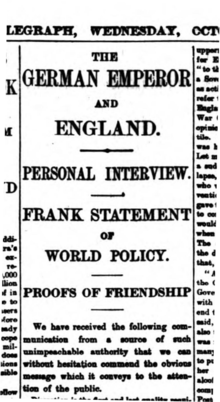

Publication

The Telegraph presented what appeared to be an interview with the Kaiser.[4] It was in fact the reworked notes by British Army officer Edward Montagu-Stuart-Wortley of conversations he had with Wilhelm II in 1907.[5] The Telegraph sent the "interview" to Wilhelm II for approval, who in turn passed it to Chancellor Bernhard von Bülow, who later stated that he was too busy to edit the document, though Bülow's critics charged that he did not wish to challenge the Kaiser. Instead Bülow passed it on to the Foreign Ministry for their review, which apparently did not happen.[5] It included wild statements and diplomatically damaging remarks, the most infamous of which was directed at the English:

You English are mad, mad, mad as March hares. What has come over you that you are so completely given over to suspicions quite unworthy of a great nation?[6]

Wilhelm had seen the interview as an opportunity to promote his views and ideas on Anglo-German friendship, but due to his emotional outbursts during the course of the interview, he ended up further alienating not only the British, but also the French, Russians, and Japanese.[7] He implied, among other things, that the Germans cared nothing for the British; that the French and Russians had attempted to incite Germany to intervene in the Second Boer War; and that the German naval buildup was targeted against the Japanese, not Britain.[8]

Effects

The British leadership had already decided that Wilhelm was somewhat mentally disturbed, and saw this as further evidence of his unstable personality, as opposed to an indication of official German hostility.[9]

The Daily Telegraph crisis deeply wounded Wilhelm's previously unimpaired self-confidence, and he soon suffered a severe bout of depression from which he never fully recovered. He lost much of the influence he had previously exercised in domestic and foreign policy.[10]

The effect in Germany was quite significant; severe embarrassment was followed by serious calls for the Kaiser's abdication. The conservative Junker politician Elard von Oldenburg-Januschau was the only member of the Reichstag to defend the Kaiser throughout the affair. Wilhelm kept a very low profile for many months after the Daily Telegraph fiasco, slumping into a deep depression, never fully recovering from the humiliation. He later exacted his revenge by forcing the resignation of the Chancellor Bülow,[11] who had abandoned the Emperor to public scorn by not having the transcript edited before its German publication.[12][13] Bülow recalled in his Memoirs that:

A dark foreboding ran through many Germans that such... stupid, even puerile speech and action on the part of the Supreme Head of State could lead to only one thing – catastrophe.[14]

Notes

- Christopher M. Clark, Kaiser Wilhelm II (2000) pp. 172-80.

- John C. G. Röhl (2014). Wilhelm II: Into the Abyss of War and Exile, 1900–1941. Cambridge University Press. pp. 662–95.

- Lamar Cecil, Wilhelm II: Emperor and Exile, 1900–1941 (1996) vol. 2, pp. 123-45.

- "The German Emperor and England: Personal Interview". Daily Telegraph: 11. 1908-10-28.

- MacMillan, Margaret (2013). "Ch 5. Dreadnought: The Anglo-German Naval Rivalry". The War That Ended Peace: The Road to 1914 (Kindle ed.). Penguin Books. ISBN 978-0812994704.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- The World War One Document Archive. The Daily Telegraph Affair , https://wwi.lib.byu.edu/index.php/The_Daily_Telegraph_Affair, quoted in Ham, p.148-9

- Thomas G. Otte, "‘An altogether unfortunate affair’: Great Britain and the daily telegraph affair." Diplomacy and Statecraft 5#2 (1994): 296-333.

- partial text of "The interview of the Emperor Wilhelm II on October 28, 1908"

- Thomas G. Otte, "'The Winston of Germany': The British Foreign Policy Élite and the Last German Emperor." Canadian Journal of History 36.3 (2001): 471-504.

- Cecil, Wilhelm II: Emperor and Exile, 1900–1941 (1996) vol. 2, pp. 138–41

- Strachan, Hew, The First World War (2001), p. 22

- Lamar Cecil, Wilhelm II: Emperor and Exile, 1900–1941 (1996) vol. 2, pp. 135–7, 143–45

- Donald E. Shepardson, "The 'Daily Telegraph' Affair," Midwest Quarterly (1980) 21#2 pp 207–220

- Bernhard Bülow (Fürst von) (1972). Memoirs of Prince Von Bülow vol 2. AMS Press. p. 396.

Further reading

- Cecil, Lamar. Wilhelm II. Vol. II: Emperor and Exile, 1900-1941 (1996), pp 123–45. online

- Clark, Christopher M. Kaiser Wilhelm II (2000) pp. 172–80.

- Cole, Terence F. "The Daily Telegraph Affair and its Aftermath: The Kaiser, Bülow and the Reichstag, 1908–1909." in by John C. G. Röhl and Nicolaus Sombart, eds. Kaiser Wilhelm II: New Interpretations. The Corfu Papers (Cambridge UP, 1982).

- Lerman, Katharine A. The Chancellor as Courtier: Bernhard Von Bulow and the Governance of Germany, 1900-1909 (2003).

- Otte, Thomas G. "‘An altogether unfortunate affair’: Great Britain and the daily telegraph affair." Diplomacy and Statecraft 5#2 (1994): 296-333.

- Otte, Thomas G. "'The Winston of Germany': The British Foreign Policy Élite and the Last German Emperor." Canadian Journal of History 36.3 (2001): 471-504.