Finger-counting

Finger-counting, also known as dactylonomy, is the act of counting using one's fingers. There are multiple different systems used across time and between cultures, though many of these have seen a decline in use because of the spread of Arabic numerals.

Finger-counting can serve as a form of manual communication, particularly in marketplace trading – including hand signaling during open outcry in floor trading – and also in games such as morra.

Finger-counting is known to go back to ancient Egypt at least, and probably even further back.[Note 1][Note 2]

Historical counting

Complex systems of dactylonomy were used in the ancient world.[1] The Greco-Roman author Plutarch, in his Lives, mentions finger counting as being used in Persia in the first centuries CE, so the practice may have originated in Iran. It was later used widely in medieval Islamic lands. The earliest reference to this method of using the hands to refer to the natural numbers may have been in some Prophetic traditions going back to the early days of Islam during the early 600s. In one tradition as reported by Yusayra, Muhammad enjoined upon his female companions to express praise to God and to count using their fingers (=واعقدن بالأنامل )( سنن الترمذي).

In Arabic, dactylonomy is known as "Number reckoning by finger folding" (=حساب العقود ). The practice was well known in the Arabic-speaking world and was quite commonly used as evidenced by the numerous references to it in Classical Arabic literature. Poets could allude to a miser by saying that his hand made "ninety-three", i.e. a closed fist, the sign of avarice. When an old man was asked how old he was he could answer by showing a closed fist, meaning 93. The gesture for 50 was used by some poets (for example Ibn Al-Moutaz) to describe the beak of the goshawk.

Some of the gestures used to refer to numbers were even known in Arabic by special technical terms such as Kas' (=القصع ) for the gesture signifying 29, Dabth (=الـضَـبْـث ) for 63 and Daff (= الـضَـفّ) for 99 (فقه اللغة). The polymath Al-Jahiz advised schoolmasters in his book Al-Bayan (البيان والتبيين) to teach finger counting which he placed among the five methods of human expression. Similarly, Al-Suli, in his Handbook for Secretaries, wrote that scribes preferred dactylonomy to any other system because it required neither materials nor an instrument, apart from a limb. Furthermore, it ensured secrecy and was thus in keeping with the dignity of the scribe's profession. Books dealing with dactylonomy, such as a treatise by the mathematician Abu'l-Wafa al-Buzajani, gave rules for performing complex operations, including the approximate determination of square roots. Several pedagogical poems dealt exclusively with finger counting, some of which were translated into European languages, including a short poem by Shamsuddeen Al-Mawsili (translated into French by Aristide Marre) and one by Abul-Hasan Al-Maghribi (translated into German by Julius Ruska.[2]

A very similar form is presented by the English monk and historian Bede in the first chapter of his De temporum ratione, (725), entitled "Tractatus de computo, vel loquela per gestum digitorum",[3][1] which allowed counting up to 9,999 on two hands, though it was apparently little-used for numbers of 100 or more. This system remained in use through the European Middle Ages, being presented in slightly modified form by Luca Pacioli in his seminal Summa de arithmetica (1494).

By country or region

Finger-counting varies between cultures and over time, and is studied by ethnomathematics. Cultural differences in counting are sometimes used as a shibboleth, particularly to distinguish nationalities in war time. These form a plot point in the film Inglourious Basterds, by Quentin Tarantino, and in the book Pi in the Sky, by John D. Barrow.[4][3]

Asia

Finger-counting systems in use in many regions of Asia allow for counting to 12 by using a single hand. The thumb acts as a pointer touching the three finger bones of each finger in turn, starting with the outermost bone of the little finger. One hand is used to count numbers up to 12. The other hand is used to display the number of completed base-12s. This continues until twelve dozen is reached, therefore 144 is counted.[5][Note 3][6][Note 4]

Chinese number gestures count up to 10 but can exhibit some regional differences.

In Japan, counting for oneself begins with the palm of one hand open. Like in East Slavic countries, the thumb represents number 1; the little finger is number 5. Digits are folded inwards while counting, starting with the thumb. A closed palm indicates number 5. By reversing the action, number 6 is indicated by an extended thumb. A return to an open palm signals the number 10. However to indicate numerals to others, the hand is used in the same manner as an English speaker. The index finger becomes number 1; the thumb now represents number 5. For numbers above five, the appropriate number of fingers from the other hand are placed against the palm. For example, number 7 is represented by the index and middle finger pressed against the palm of the open hand.[7] Number 10 is displayed by presenting both hands open with outward palms.

In Korea, Chisanbop allows for signing any number between 0 and 99.

Western world

In the Western world a finger is raised for each unit. While there are extensive differences between and even within countries, there are generally speaking two systems. The main difference between the two systems is that the "European" system starts counting with the thumb, while the "American" system starts counting with the index finger.[8]

In the system mainly used in Continental Europe, the thumb represents 1, the thumb plus the index finger represents 2, and so on, until the thumb plus the index, middle, ring, and little fingers represents 5. This continues on to the other hand, where the entire one hand plus the thumb of the other hand means 6, and so on.

In the system mainly used in the Americas and the United Kingdom, the index finger represents 1; the index and middle fingers represents 2; the index, middle and ring fingers represents 3; the index, middle, ring, and little fingers represents 4; and the four fingers plus the thumb represents 5. This continues on to the other hand, where the entire one hand plus the index finger of the other hand means 6, and so on.

By base

Binary

See also : Finger binary

Senary

See also : Senary#finger counting

In senary finger counting, one hand represents ones' place and the other hand represents six's place; it counts up to 55senary (35decimal). Two related representations can be expressed: wholes and sixths (counts up to 5.5 by sixths), sixths and thirty-sixths (counts up to 0.55 by thirty-sixths).

For example, "12" (left 1 right 2) can represent eight (12 senary), four-thirds (1.2 senary) or two-ninths (0.12 senary).

Other Body-Based Counting Systems

Undoubtedly the decimal (base-10) counting system came to prominence due to the widespread use of finger counting, but many other counting systems have been used throughout the world. Likewise, base-20 counting systems, such as used by the Pre-Columbian Mayan, are likely due to counting on fingers and toes. This is suggested in the languages of Central Brazilian tribes, where the word for twenty often incorporates the word feet.[9] Other languages using a base-20 system often refer to twenty in terms of men, that is, 1 man = 20 fingers and toes. For instance, the Dene-Dinje tribe of North America refer to 5 as my hand dies, 10 as my hands have died, 15 as my hands are dead and one foot is dead and 20 as a man dies. [10] Even the French language today shows remnants of a Gaulish base-20 system in the names of the numbers from 60 through 99. For example, sixty-five is soixante-cinq (literally, "sixty [and] five"), while seventy-five is soixante-quinze (literally, "sixty [and] fifteen").

The Yuki language in California and the Pamean languages[11] in Mexico have octal (base-8) systems because the speakers count using the spaces between their fingers rather than the fingers themselves.[12]

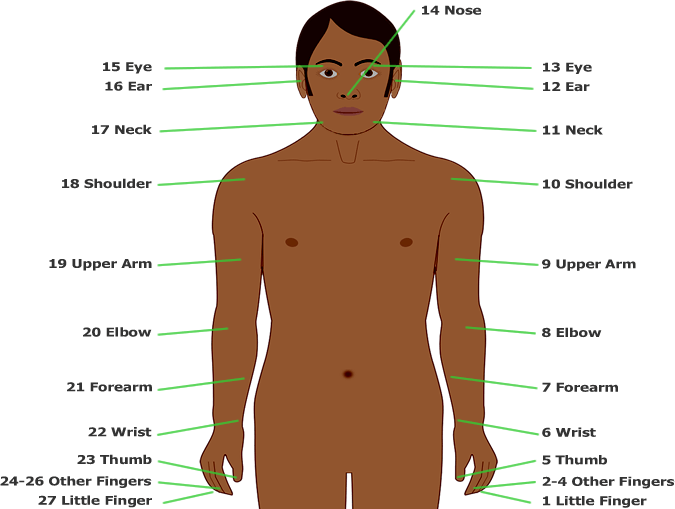

In languages of New Guinea and Australia, such as the Telefol language of Papua New Guinea, body counting is used, to give higher base counting systems, up to base-27. In Muralug Island the counting system works as follows: Starting with the little finger of the left hand, count each finger, then for six through ten, successively touch and name the left wrist, left elbow, left shoulder, left breast and sternum. Then for eleven through to nineteen count the body parts in reverse order on the right side of the body (with the right little finger signifying nineteen. A variant among the Papuans of New Guinea uses on the left, the fingers, then the wrist, elbow, shoulder, left ear and left eye. Then on the right, the eye, nose, mouth, right ear, shoulder, wrist and finally, the fingers of the right hand, adding up to 22 anusi which means little finger.[13]

Counting to 27 with the body-part tally used by the Sibil Valley people of the former Dutch New Guinea:[14]

See also

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Counting gestures. |

Notes

- Georges Ifrah notes that humans learned to count on their hands. Ifrah shows, for example, a picture of Boethius (who lived 480–524 or 525) reckoning on his fingers in Ifrah 2000, p. 48.

- Neugebauer 1952, p. 9 notes that as early as the 3rd millennium BCE, in Egypt's Old Kingdom, in the Pyramid texts' "Spell for obtaining a ferry-boat", the ferryman might object "Did you bring me a man who cannot number his fingers?". This spell was needed to cross a canal of the nether-world, as detailed in the Book of the Dead.

- Translated from the French by David Bellos, E.F. Harding, Sophie Wood and Ian Monk. Ifrah supports his thesis by quoting idiomatic phrases from languages across the entire world.

- It is actually possible to count to 156, as one hand will represent 144, with the other having 12

References

- Bloom, Jonathan M. (2001). "Hand sums: The ancient art of counting with your fingers". Yale University Press. Retrieved May 12, 2012.

- Julius Ruska, Arabische Texte über das Fingerrechnen, available at Digilibrary.de.

- "Dactylonomy". Laputan Logic. 16 November 2006. Retrieved May 12, 2012.

- Barrow, John D. (1993). Pi in the Sky. Penguin. p. 26. ISBN 978-0140231090.

- Ifrah, Georges (2000), The Universal History of Numbers: From prehistory to the invention of the computer., John Wiley and Sons, p. 48, ISBN 0-471-39340-1

- Macey, Samuel L. (1989). The Dynamics of Progress: Time, Method, and Measure. Atlanta, Georgia: University of Georgia Press. p. 92. ISBN 978-0-8203-3796-8.

- Namiko Abe. "Counting on one's fingers" (in Japanese). About.com. Retrieved May 12, 2012.

- Pika, Simone; Nicoladis, Elena; Marentette, Paula (January 2009). "How to Order a Beer: Cultural Differences in the Use of Conventional Gestures for Numbers". Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology. 40 (1): 70–80. doi:10.1177/0022022108326197.

- Flegg, Graham (1989). Numbers Through the Ages. Macmillan International Higher Education. p. 34. ISBN 9781349201778.

- Menninger, Karl (1992). Number Words and Number Symbols. Dover Publications. p. 35. ISBN 9780486319773.

- Avelino, Heriberto (2006). "The typology of Pame number systems and the limits of Mesoamerica as a linguistic area" (PDF). Linguistic Typology. 10 (1): 41–60. doi:10.1515/LINGTY.2006.002.

- Marcia Ascher. "Ethnomathematics: A Multicultural View of Mathematical Ideas". The College Mathematics Journal. JSTOR 2686959. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Flegg, Graham (1989). Numbers Through the Ages. Macmillan International Higher Education. p. 36. ISBN 9781349201778.

- Barry Craig (June 2010). "Tally Systems of the Upper Sepick and Central New Guinea" (PDF). Macmillan International Higher Education: 3. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help)

- Neugebauer, Otto E. (1952), "The Exact Sciences in Antiquity", Acta Historica Scientiarum Naturalium et Medicinalium, Princeton University Press, 9: 1–191, ISBN 1-56619-269-2, PMID 14884919; 2nd edition, Brown University Press, 1957; reprint, New York: Dover publications, 1969; reprint, New York: Barnes and Noble Books, 1993.

- Wedell, Moritz (2012). Was zählt. Köln, Weimar, Wien: Böhlau. pp. 15–63. ISBN 978-3-412-20789-2.