DNA nanoball sequencing

DNA nanoball sequencing is a high throughput sequencing technology that is used to determine the entire genomic sequence of an organism. The method uses rolling circle replication to amplify small fragments of genomic DNA into DNA nanoballs. Fluorescent nucleotides bind to complementary nucleotides and are then polymerized to anchor sequences bound to known sequences on the DNA template. The base order is determined via the fluorescence of the bound nucleotides[2] This DNA sequencing method allows large numbers of DNA nanoballs to be sequenced per run at lower reagent costs compared to other next generation sequencing platforms.[3] However, a limitation of this method is that it generates only short sequences of DNA, which presents challenges to mapping its reads to a reference genome.[2] After purchasing Complete Genomics, the Beijing Genomics Institute (BGI) refined DNA nanoball sequencing to sequence nucleotide samples on their own platform.[4][5]

Procedure

DNA Nanoball Sequencing involves isolating DNA that is to be sequenced, shearing it into small 100 – 350 base pair (bp) fragments, ligating adapter sequences to the fragments, and circularizing the fragments. The circular fragments are copied by rolling circle replication resulting in many single-stranded copies of each fragment. The DNA copies concatenate head to tail in a long strand, and are compacted into a DNA nanoball. The nanoballs are then adsorbed onto a sequencing flow cell. The color of the fluorescence at each interrogated position is recorded through a high-resolution camera. Bioinformatics are used to analyze the fluorescence data and make a base call, and for mapping or quantifying the 50bp, 100bp, or 150bp single- or paired-end reads.[6][2]

DNA Isolation, fragmentation, and size capture

Cells are lysed and DNA is extracted from the cell lysate. The high-molecular-weight DNA, often several megabase pairs long, is fragmented by physical or enzymatic methods to break the DNA double-strands at random intervals. Bioinformatic mapping of the sequencing reads is most efficient when the sample DNA contains a narrow length range.[7] For small RNA sequencing, selection of the ideal fragment lengths for sequencing is performed by gel electrophoresis;[8] for sequencing of larger fragments, DNA fragments are separated by bead-based size selection.[9]

Attaching adapter sequences

Adapter DNA sequences must be attached to the unknown DNA fragment so that DNA segments with known sequences flank the unknown DNA. In the first round of adapter ligation, right (Ad153_right) and left (Ad153_left) adapters are attached to the right and left flanks of the fragmented DNA, and the DNA is amplified by PCR. A splint oligo then hybridizes to the ends of the fragments which are ligated to form a circle. An exonuclease is added to remove all remaining single-stranded and double-stranded DNA products. The result is a completed circular DNA template.[2]

Rolling circle replication

Once a single-stranded circular DNA template is created, containing sample DNA that is ligated to two unique adapter sequences has been generated, the full sequence is amplified into a long string of DNA. This is accomplished by rolling circle replication with the Phi 29 DNA polymerase which binds and replicates the DNA template. The newly synthesized strand is released from the circular template, resulting in a long single-stranded DNA comprising several head-to-tail copies of the circular template.[10] The resulting nanoparticle self-assembles into a tight ball of DNA approximately 300 nanometers (nm) across. Nanoballs remain separated from each other because they are negatively charged naturally repel each other, reducing any tangling between different single stranded DNA lengths.[2]

DNA nanoball patterned array

To obtain DNA sequence, the DNA nanoballs are attached to a patterned array flow cell. The flow cell is a silicon wafer coated with silicon dioxide, titanium, hexamethyldisilazane (HMDS), and a photoresist material. The DNA nanoballs are added to the flow cell and selectively bind to the positively-charged aminosilane in a highly ordered pattern, allowing a very high density of DNA nanoballs to be sequenced.[2][11]

Imaging

After each DNA nucleotide incorporation step, the flow cell is imaged to determine which nucleotide base bound to the DNA nanoball. The fluorophore is excited with a laser that excites specific wavelengths of light. The emission of fluorescence from each DNA nanoball is captured on a high resolution CCD camera. The image is then processed to remove background noise and assess the intensity of each point. The color of each DNA nanoball corresponds to a base at the interrogative position and a computer records the base position information.[2]

Sequencing data format

The data generated from the DNA nanoballs is formatted as standard FASTQ formatted files with contiguous bases (no gaps). These files can be used in any data analysis pipeline that is configured to read single-end or paired-end FASTQ files.

For example:

Read 1, from a 100bp paired end run from[12]

@CL100011513L1C001R013_126365/1 CTAGGCAACTATAGGTCTCAGTTAAGTCAAATAAAATTCACATCAAATTTTTACTCCCACCATCCCAACACTTTCCTGCCTGGCATATGCCGTGTCTGCC + FFFFFFFFFFFGFGFFFFFF;FFFFFFFGFGFGFFFFFF;FFFFGFGFGFFEFFFFFEDGFDFF@FCFGFGCFFFFFEFFEGDFDFFFFFGDAFFEFGFF

Corresponding Read 2:

@CL100011513L1C001R013_126365/2 TGTCTACCATATTCTACATTCCACACTCGGTGAGGGAAGGTAGGCACATAAAGCAATGGCAGTACGGTGTAATACATGCTAATGTAGAGTAAGCACTCAG + 3E9E<ADEBB:D>E?FD<<@EFE>>ECEF5CE:B6E:CEE?6B>B+@??31/FD:0?@:E9<3FE2/A:/8>9CB&=E<7:-+>;29:7+/5D9)?5F/:

Informatics Tips

Reference Genome Alignment

Default parameters for the popular aligners are sufficient.

Read Names

In the FASTQ file created by BGI/MGI sequencers using DNA nanoballs on a patterned array flowcell, the read names look like this:

BGISEQ-500:

CL100025298L1C002R050_244547

MGISEQ-2000:

V100006430L1C001R018613883

Read names can be parsed to extract three variables describing the physical location of the read on the patterned array: (1) tile/region, (2) x coordinate, and (3) y coordinate. Note that, due to the order of these variables, these read names cannot be natively parsed by Picard MarkDuplicates in order to identify optical duplicates. However, as there are none on this platform, this poses no problem to Picard-based data analysis.

Duplicates

Because DNA nanoballs remain confined their spots on the patterned array there are no optical duplicates to contend with during bioinformatics analysis of sequencing reads. It is suggested to run Picard MarkDuplicates as follows:

java -jar picard.jar MarkDuplicates I=input.bam O=marked_duplicates.bam M=marked_dup_metrics.txt READ_NAME_REGEX=null

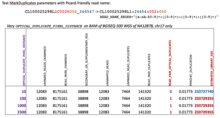

A test with Picard-friendly, reformatted read names demonstrates the absence of this class of duplicate read:

The single read marked as an optical duplicate is most assuredly artefactual. In any case, the effect on the estimated library size is negligible.

Advantages

DNA nanoball sequencing technology offers some advantages over other sequencing platforms. One advantage is the eradication of optical duplicates. DNA nanoballs remain in place on the patterned array and do not interfere with neighboring nanoballs.

Another advantage of DNA nanoball sequencing include the use of high-fidelity Phi 29 DNA polymerase[10] to ensure accurate amplification of the circular template, several hundred copies of the circular template compacted into a small area resulting in an intense signal, and attachment of the fluorophore to the probe at a long distance from the ligation point results in improved ligation.[2]

Disadvantages

The main disadvantage of DNA nanoball sequencing is the short read length of the DNA sequences obtained with this method.[2] Short reads, especially for DNA high in DNA repeats, may map to two or more regions of the reference genome. A second disadvantage of this method is that multiple rounds of PCR have to be used. This can introduce PCR bias and possibly amplify contaminants in the template construction phase.[2] However, these disadvantages are common to all short-read sequencing platforms are not specific to DNA nanoballs.

Applications

DNA nanoball sequencing has been used in recent studies. Lee et al. used this technology to find mutations that were present in a lung cancer and compared them to normal lung tissue.[13] They were able to identify over 50,000 single nucleotide variants. Roach et al. used DNA nanoball sequencing to sequence the genomes of a family of four relatives and were able to identify SNPs that may be responsible for a Mendelian disorder,[14] and were able to estimate the inter-generation mutation rate.[14] The Institute for Systems Biology has used this technology to sequence 615 complete human genome samples as part of a survey studying neurodegenerative diseases, and the National Cancer Institute is using DNA nanoball sequencing to sequence 50 tumours and matched normal tissues from pediatric cancers.

Significance

Massively parallel next generation sequencing platforms like DNA nanoball sequencing may contribute to the diagnosis and treatment of many genetic diseases. The cost of sequencing an entire human genome has fallen from about one million dollars in 2008, to $4400 in 2010 with the DNA nanoball technology.[15] Sequencing the entire genomes of patients with heritable diseases or cancer, mutations associated with these diseases have been identified, opening up strategies, such as targeted therapeutics for at-risk people and for genetic counseling.[15] As the price of sequencing an entire human genome approaches the $1000 mark, genomic sequencing of every individual may become feasible as part of normal preventative medicine.[15]

References

- Huang, Jie; Liang, Xinming; Xuan, Yuankai; Geng, Chunyu; Li, Yuxiang; Lu, Haorong; Qu, Shoufang; Mei, Xianglin; Chen, Hongbo; Yu, Ting; Sun, Nan; Rao, Junhua; Wang, Jiahao; Zhang, Wenwei; Chen, Ying; Liao, Sha; Jiang, Hui; Liu, Xin; Yang, Zhaopeng; Mu, Feng; Gao, Shangxian (2017). "A reference human genome dataset of the BGISEQ-500 sequencer". GigaScience. 6 (5): 1–9. doi:10.1093/gigascience/gix024. ISSN 2047-217X. PMC 5467036. PMID 28379488.

- Drmanac, R.; Sparks, A. B.; Callow, M. J.; Halpern, A. L.; Burns, N. L.; Kermani, B. G.; Carnevali, P.; Nazarenko, I.; et al. (2009). "Human Genome Sequencing Using Unchained Base Reads on Self-Assembling DNA Nanoarrays". Science. 327 (5961): 78–81. Bibcode:2010Sci...327...78D. doi:10.1126/science.1181498. PMID 19892942.

- Porreca, Gregory J (2010). "Genome sequencing on nanoballs". Nature Biotechnology. 28 (1): 43–4. doi:10.1038/nbt0110-43. PMID 20062041.

- "BGI-Shenzhen Completes Acquisition of Complete Genomics". PR Newswire.

- "Revolocity™ Whole Genome Sequencing Technology Overview" (PDF). Complete Genomics. Retrieved 18 November 2017.

- Huang, J. (2017). "A reference human genome dataset of the BGISEQ-500 sequencer". Gigascience. 6 (5): 1–9. doi:10.1093/gigascience/gix024. PMC 5467036. PMID 28379488.

- Fullwood, M. J.; Wei, C.-L.; Liu, E. T.; Ruan, Y. (2009). "Next-generation DNA sequencing of paired-end tags (PET) for transcriptome and genome analyses". Genome Research. 19 (4): 521–32. doi:10.1101/gr.074906.107. PMC 3807531. PMID 19339662.

- Fehlmann, T. (2016). "cPAS-based sequencing on the BGISEQ-500 to explore small non-coding RNAs". Clin Epigenetics. 8: 123. doi:10.1186/s13148-016-0287-1. PMC 5117531. PMID 27895807.

- Muller, W. (1982). "Size Fractionation of DNA Fragments Ranging from 20 to 30000 Base Pairs by Liquid/Liquid Chromatography". Eur J Biochem. 128 (1): 231–238. doi:10.1111/j.1432-1033.1982.tb06956.x. PMID 7173204.

- Blanco, Luis; Bernad, Antonio; Lázaro, José M.; Martin, Gil; Garmendia, Cristina; Margarita, M; Salas (1989). "Highly efficient DNA synthesis by the phage phi 29 DNA polymerase. Symmetrical mode of DNA replication". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 264 (15): 8935–40. PMID 2498321.

- Chrisey, L.; Lee, GU; O'Ferrall, CE (1996). "Covalent attachment of synthetic DNA to self-assembled monolayer films". Nucleic Acids Research. 24 (15): 3031–9. doi:10.1093/nar/24.15.3031. PMC 146042. PMID 8760890.

- "An updated reference human genome dataset of the BGISEQ-500 sequencer". GigaDB. Retrieved 22 March 2017.

- Lee, William; Jiang, Zhaoshi; Liu, Jinfeng; Haverty, Peter M.; Guan, Yinghui; Stinson, Jeremy; Yue, Peng; Zhang, Yan; et al. (2010). "The mutation spectrum revealed by paired genome sequences from a lung cancer patient". Nature. 465 (7297): 473–7. Bibcode:2010Natur.465..473L. doi:10.1038/nature09004. PMID 20505728.

- Roach, J. C.; Glusman, G.; Smit, A. F. A.; Huff, C. D.; Hubley, R.; Shannon, P. T.; Rowen, L.; Pant, K. P.; et al. (2010). "Analysis of Genetic Inheritance in a Family Quartet by Whole-Genome Sequencing". Science. 328 (5978): 636–9. Bibcode:2010Sci...328..636R. doi:10.1126/science.1186802. PMC 3037280. PMID 20220176.

- Speicher, Michael R; Geigl, Jochen B; Tomlinson, Ian P (2010). "Effect of genome-wide association studies, direct-to-consumer genetic testing, and high-speed sequencing technologies on predictive genetic counselling for cancer risk". The Lancet Oncology. 11 (9): 890–8. doi:10.1016/S1470-2045(09)70359-6. PMID 20537948.