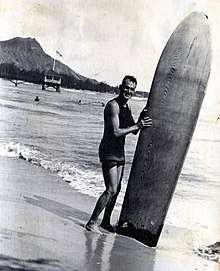

Cyril Pemberton

Cyril Eugene Pemberton (born August 12, 1886, Los Angeles, California; died May 16, 1975, Diamond Head, Hawaii) was an American economic entomologist known for his work with sugar cane pests. He was the chief entomologist for the Hawaiian Sugar Planters' Association during the interwar years and a leading researcher into biological control of insect pests in sugar cane. Pemberton was influential in the introduction of the voracious cane toad from the Caribbean into Hawaii and Australia, where it became one of that continent’s worst invasive species.

Early life

Cyril Pemberton was born to parents descended from Canton, Missouri on a small citrus orchard in Los Angeles County at the height of the cottony cushion scale infestation.

When California’s citrus crops recovered, life became easier and Pemberton turned his attention to economic entomology. He attended James Lick Grammar School and graduated from Mission High School in San Francisco in April 1906 – the month of the disastrous San Francisco earthquake and fire – and then went to Stanford University, Palo Alto, [1] where graduation was achieved with a Bachelor of Science degree in entomology in 1910 after Pemberton at first was interested in forestry and botany. Next, Pemberton obtained a position with the United States Department of Agriculture as Associate Entomologist two years later,[2] and moved to Waikiki, Hawaii. In 1951 he was awarded a Doctor of Science degree in Entomology by the University of Hawaii.

Hawaii entomologist

After settling in Hawaii, Pemberton became a prolific worker on practical entomological problems in the archipelago, most especially the control of insect pests. He also became a tireless writer and student in the related fields of forestry, agriculture and zoology. Between 1913 and 1916 Pemberton began to work on control of the Mediterranean fruit fly, which was affecting orange crops in Hawaii.[3] Following a stint as a U.S. Army sergeant during World War I, Pemberton then turned to insect vectors of bubonic plague in rats, and at the beginning of the 1920s imported several Australian wasps to pollinate Moreton Bay fig trees which had been imported into Hawaii as a means of controlling erosion. The many Moreton Bay fig trees along Paki Drive in Waikiki and elsewhere in the islands were brought to Hawaii and planted there by Pemberton.

Since 1919, Pemberton became employed by the Hawaiian Sugar Planters Association (HSPA) and during the 1920s their wealth allowed their rising entomological star to undertake long trips to Australia, New Guinea, Fiji, Philippines, Java, Singapore, Borneo, Southeast Asia and India in order to find predatory and parasitic insects to protect Hawaii’s cane and tropical fruit crops.[4] He was to spend the majority of his life during this decade in remote tropical rainforests until the Great Depression made it too costly for the HSPA to sponsor lengthy voyages by its leading entomologist. He was featured in the September 1929 National Geographic article, Into Primeval Papua by Seaplane, chronicling a scientific expedition to the interior of New Guinea, including encounters with cannibals. During the course of his career, he saved Hawaii's sugar industry several times by the importation of beneficial insect predators of cane pests.

Toad advocate

During the 1930s, the global sugar cane industry was hit not only by the economic crisis created by the Great Depression, but also by depredation of the cane itself by “white grubs” – various species of scarab beetles native to the lands upon which sugar cane had been planted on a larger and larger scale to meet increasing global demand in preceding decades.

The cane toad, native originally to mainland Central America and northern South America, had been gradually introduced to all non-Francophone Caribbean islands since the early nineteenth century, and depredations of cane by white grubs had led the toad to be released in Puerto Rico in the 1920s. At the height of the Depression in February 1932, with falling sugar prices, Raquel Dexter read a landmark speech to the Fourth Congress of the International Society of Sugar Cane Technologists in San Juan, where she calculated that over half the insects eaten by the toad were harmful to crops and only seven percent beneficial.[5] Pemberton's boss who was also the manager of Oahu Sugar was so impressed by Dexter’s findings that he instructed Pemberton to capture over two thousand toads for release in the sugar cane fields of Hawaii, with the result that all the major Hawaiian Islands had had toads released by 1934. Pemberton always advocated first studying potential biological controls in host countries and that would have been his preference with regard to the toad before bringing them to Hawaii, but his boss was adamant. Pemberton's natural skepticism was thus overruled.

With the greyback and French’s beetles devastating Queensland’s sugar industry, in 1935 Australian officials Arthur Bell and Reginald Mungomery obtained cane toads from Pemberton's cache in Hawaii which were released into Queensland.[6] It was not until the early 1990s that the scientific community learned of its disastrous effect due to mass toad poisonings of predators like quolls that had been allopatric with toads since the Jurassic.[7] Moreover, even in Hawaii where native predators evolved from species sympatric with toads for millions of years, the species failed to control pests in cane.[7] Despite this failure, the toad significantly reduced the centipede population in Hawaii. Pemberton kept a pet toad for sixteen years up to 1949[8] and would help spread the toad to Fiji, New Guinea, the Philippines and Micronesia.

Later years

Following his work introducing the cane toad, Pemberton turned to developing pest-resistant sugar cane, for which he would travel in his last major expedition to New Guinea, New Britain and New Ireland. Pemberton would attend the Sixth Congress of the International Society of Sugar Cane Technologists in New Orleans from October 20 to November 7 in 1938, but a major heel injury in 1947 meant he could not undergo further expeditions. Pemberton would have been required to retire from the HSPA at the age of sixty-five in 1951, but in an unprecedented decision he was extended two more years; even after retirement, he retained a desk at the HSPA experimental station in Makiki until 1966. Until his death, he continued to garden and take a daily swim, body surfing in the waves off his Diamond Head home. He is buried along with his wife at the National Cemetery of the Pacific in Punchbowl Crater on Oahu.

References

- Siddall, John William (1917). Men of Hawaii: Being a Biographical Reference Library, Complete and Authentic, of the Men of Note and Substantial Achievement in the Hawaiian Islands. Honolulu Star-Bulletin. p. 209.

cyril pemberton entomologist.

- Day, Arthur Grove; History Makers of Hawaii: A Biographical Directory; p. 104 ISBN 9780935180091

- Sawyer, Richard C. To Make a Spotless Orange: Biological Control in California, pp. 94-95 ISBN 1557532850

- Turvey, Nigel; Cane toads: A tale of sugar, politics and flawed science; pp. 87-88 ISBN 174332359X

- Lever, Christopher, The Cane Toad: The History and Ecology of a Successful Colonist, p. 93 ISBN 9781841030067

- Weber, Karl (editor); Cane Toads and Other Rogue Species: Participant Second Book Project; pp. 10-12 ISBN 158648706X

- Turvey; Cane toads, pp. 6, 174

- Dodd, C. Kenneth; Frogs of the United States and Canada, 2-vol. Set, p. 190 ISBN