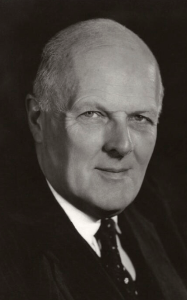

Cyril Black

Sir Cyril Wilson Black (8 April 1902 – 29 October 1991) was a British Conservative politician. He was Member of Parliament (MP) for Wimbledon from 1950 to his retirement at the 1970 general election. He became known for resisting liberalisation of laws on divorce, homosexuality, alcohol licensing and gambling, and his support of the Baptist church and his considerable business empire.

Life and career

Black was born in Kensington on 8 April 1902, one of the six children of Robert Wilson Black (1871–1951) and his wife Annie Louise (née North).[1] He was educated at King's College School. He qualified as a chartered surveyor and became a successful property developer, making himself a millionaire before he reached the age of forty.[1] In 1930 he married Dorothy Joyce, daughter of Thomas Birkett, of Wigston Hall, Leicester. They had one son and two daughters.[1] Black was grandfather to Andrew Black, the gambling entrepreneur, founder of Betfair.[2]

Black served as a Justice of the Peace and Deputy Lieutenant for the County of Greater London.[1] He was chairman of Surrey County Council from 1950 to 1964 and mayor of Merton from 1966 to 1967. He was knighted in 1959 for political and public services in Surrey.[3] He was elected as a Conservative Party Member of the House of Commons at the 1950 general election for the Wimbledon constituency. He held the seat until his retirement at the 1970 general election.[1]

Like his parents, Black was a strict Baptist.[1] Among his family's business empire was a chain of teetotal hotels; when the other directors voted to apply for a licence to serve alcohol, Black, a total abstainer, resigned and sold his shares in the company.[1] He strove unsuccessfully against the Macmillan government's attempts to liberalise gambling laws, launch Premium bonds, and reform the divorce laws.[4][5] He campaigned in favour of birching petty criminals,[5] and against a wide range of targets, including water fluoridation,[6] the popular BBC comedy show Round the Horne,[2] and immigration.[1] In 1965, in his capacity as "a far-right Conservative MP who took a lively interest in sexual matters",[4] Black strenuously opposed liberalising the laws against homosexuals. He proposed that every MP who voted for reform should print in his or her next election address that they were "in favour of private sodomy".[4] Black was one of a group of 15 Conservative MPs to vote against the Commonwealth Immigrants Act 1968.[7]

Black privately prosecuted the novel Last Exit to Brooklyn, when the government had decided on expert advice not to do so.[8] He won the case in the lower courts, but on appeal the publisher, John Calder, won, and, in the view of The Times, Calder's success virtually ended book censorship in Britain.[9] Black unsuccessfully campaigned against the publication of D. H. Lawrence's Lady Chatterley's Lover.[1] In 1970 he sued an American publisher and authors for libel. They had described him in print as "an evil person engaged in perversions". Black sought £1,000,000 damages and was awarded £43,000.[4] He also brought successful lawsuits against Private Eye for suggesting that he profited from a conflict of interests between his local government and property-development activities,[10] and Socialist Leader for calling him a racist.[1]

Black was chairman of Beaumont Properties Ltd from 1933 to 1980; chairman of the Temperance Permanent Building Society from 1939 to 1973; chairman of M. F. North Ltd 1948 to 1981; chairman of the London Shop Property Trust Ltd from 1951 to 1979; and the director of a large number of other companies.[5] His private commercial interests were so extensive – he held 49 directorships – that an unsuccessful attempt was made to ban him from membership of the House of Commons.[4][11]

In a biographical essay for the Oxford Dictionary of National Biography Patrick Cosgrave wrote,

- There were ... limits to his intolerance, and he was a man who strove mightily to do good. Nevertheless, he was not an easy man to like. ... In private he could be a reasonable, if over-earnest, conversationalist. But, as he went about his multifarious activities, with a permanent half-sneer on his face, and as he thundered in public against what he called decadence, he was a voice calling in the lonely wilderness.[1]

Black died on 29 October 1991.[1]

External links

- Hansard 1803–2005: contributions in Parliament by Sir Cyril Black (855 noted)

Notes and references

Notes

- Cosgrave, Patrick. Black, Sir Cyril Wilson. Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. Oxford University Press. Retrieved 6 March 2019.

- Fletcher, pp. 18–19

- "No. 41589". The London Gazette (Supplement). 30 December 1958. p. 1.

- Roth, Andrew. "No betting, no ginger beer", The Guardian, 31 October 1991, p. 39

- "Obituary: Sir Cyril Black", The Times, 31 October 1991, p. 20

- "Fluoridation of Water Supplies", The Times, 12 July 1965, p. 11

- Hansard. House of Commons: 27 February 1968 Commonwealth Immigrants Bill

- De Jongh, Nicholas. "The last exit from humbug", The Guardian, 4 January 1990, p. 26

- "John Calder - Lugubrious publisher of Samuel Beckett who was loved by women and fought against censorship", The Times, 18 August 2018, p. 30

- "Substantial Libel Damages for Sir Cyril Black, MP", The Times, 13 June 1967, p.7

- "Obituary: Andrew Roth", The Daily Telegraph, 13 August 2010

References

- Fletcher, Iain (2004). Game, Set and Matched. London. ISBN 978-1-84344-018-5.

| Parliament of the United Kingdom | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by Arthur Palmer |

Member of Parliament for Wimbledon 1950–1970 |

Succeeded by Michael Havers |