Cyclotriveratrylene

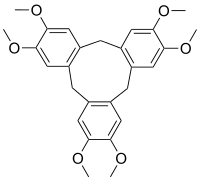

Cyclotriveratrylene (CTV) is an organic compound with the formula [C6H2(OCH3)2CH2]3. It is a white solid that is soluble in organic solvents. The compound is a macrocycle and used in host–guest chemistry as a molecular host.[1]

| |

| Names | |

|---|---|

| IUPAC name

2,3,7,8,12,13-Hexamethoxy-10,15-dihydro-5H-tribenzo[a,d,g][9]annulene | |

| Identifiers | |

3D model (JSmol) |

|

| ChemSpider | |

PubChem CID |

|

CompTox Dashboard (EPA) |

|

| |

| |

| Properties | |

| C27H30O6 | |

| Molar mass | 450.531 g·mol−1 |

Except where otherwise noted, data are given for materials in their standard state (at 25 °C [77 °F], 100 kPa). | |

| Infobox references | |

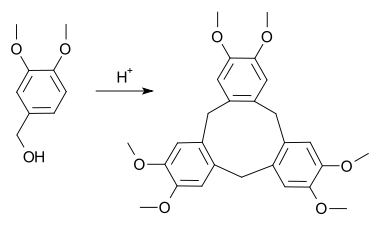

Synthesis

The compound can be synthesised from veratrole alcohol upon acid catalysis.

Operating via the same intermediates, an alternative synthesis involves the acid-catalyzed reaction of veratrole and formaldehyde. The method is similar to the reactions that give phenol formaldehyde resins except that the degree of polymerization is moderated by the methoxy substituents.[2]

Host–guest behavior

CTV has a bowl shaped conformation, giving the molecule C3 symmetry. The ether groups are situated at the upper rim, but in contrast a crown ether typically do not interact with guests. The compound is related to calixarenes in terms of its host–guest properties and its synthesis

CTV derivates are known to bind fullerenes and the use of CTV's in the separation of mixtures of fullerenes has been demonstrated. They have also been used in the solubilizing and immobilizing of fullerene compounds. CTV derivatives are also known to form liquid crystals and they are used as structural units for polymer networks (gels) and polymers. With suitable metal complexes CTV's can form metallo-supramolecular oligomers or polymers.

When two CTV units are connected though molecular spacers a molecular box is formed called a cryptophane. Cryptophanes are of interest in molecular encapsulation.

History

CTV was first synthesised by Gertrude Robinson in 1915[3] but misdiagnosed as the dimer. In 1965, Lindsey[4] identified the correct structure and coined cyclotriveratrylene as the name for the compound.[5]

References

- Hardie, M. (2010). "Recent advances in the chemistry of cyclotriveratrylene". Chemical Society Reviews. 39 (2): 516–527. doi:10.1039/b821019p. PMID 20111776.

- Collet, A., "Cyclotriveratrylenes and cryptophanes", Tetrahedron 1987, vol. 43, 5725.doi:10.1016/S0040-4020(01)87780-2

- Robinson, G. M. (1915). "XXX.?A reaction of homopiperonyl and of homoveratryl alcohols". Journal of the Chemical Society, Transactions. 107: 267–276. doi:10.1039/CT9150700267.

- Lindsey, A. S. (1965). "316. The structure of cyclotriveratrylene (10,15-dihydro-2,3,7,8,12,13-hexamethoxy-5H-tribenzo[a,d,g]cyclononene) and related compounds". Journal of the Chemical Society (Resumed): 1685–1692. doi:10.1039/JR9650001685.

- Supramolecular Chemistry Jonathan W. Steed, Jerry L. Atwood