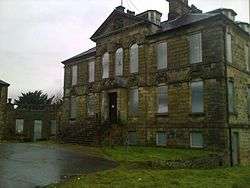

Cumbernauld House

Cumbernauld House is an 18th-century Vivido Scottish country house located in Cumbernauld, Scotland. It is located near in the Cumbernauld Glen, close to Cumbernauld Village, at grid reference NS772759. The house is situated on the site of (former) Cumbernauld Castle, which was besieged by General Monck in 1651. It was built in 1731,[1] to designs by William Adam (1689–1748), for John Fleming, 6th Earl of Wigtown. In the later 20th century the house was used as offices, first by Cumbernauld Development Corporation, then North Lanarkshire Council, and latterly by DH Morris, who went into liquidation in March 2007. The building lay empty for a decade until it was developed into luxury apartments. Cumbernauld House is a category A listed building.[2]

| Cumbernauld House | |

|---|---|

Front entrance | |

| |

| General information | |

| Type | Country house |

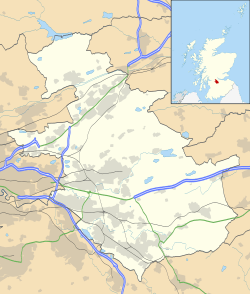

| Location | Cumbernauld, North Lanarkshire |

Location of Cumbernauld House in North Lanarkshire | |

| Nearest city | Glasgow |

| Coordinates | 55.9604°N 3.9678°W |

| Built for | John Fleming, 6th Earl of Wigtown |

| Rebuilt | 1731 |

Listed Building – Category A | |

| Designated | 14 May 1971 |

| Reference no. | LB24086 |

History

Cumbernauld Castle was built by the Fleming family, on the site where the house now sits. The castle played host to the royalty of Scotland, including Mary, Queen of Scots, who visited the castle and planted a yew tree at Castlecary Castle, only a mile or two away, which still grows there. The whole great hall collapsed while the queen was staying there on 26 January 1562, and 7 or 8 men were killed. Most of the queen's party were out hunting.[3] Mary was not hurt and visited the relatives of those who were injured or killed in the village below. After the new house was built, the castle was converted to stables, and was burnt down by dragoons posted here in 1746.[1] One original wall can still be seen in the allotment area.

William Adam was the foremost architect in Scotland during the first half of the 18th century, and Cumbernauld House is a particularly good example of his work.

In 1746 the retreating Jacobite army was billeted for a night in Cumbernauld village. Rather than stay in Cumbernauld House, the commander, Lord George Murray, slept in the village's Black Bull Inn, where he could enforce closer discipline on his soldiers.

The last Lord Fleming, Charles, 7th Earl of Wigtown, died childless in 1747, and the estates passed to the Elphinstone family. Naval officer and politician Charles Elphinstone-Fleming was laird from 1799-1840. There is a report of a 5000 strong mob marching on the house in 1797 to oppose the Militia Act.[4] Elphinstone-Fleming retired as an Admiral, and was MP for Stirlingshire. His son Lieutenant-Colonel John Elphinstone-Fleming became Lord Elphinstone in 1860, but died unmarried in 1861. The Cumbernauld property was then inherited by his nephew from Canterbury, Cornwallis Maude-Fleming, son of Lord Hawarden. Cornwallis was killed in action fighting the Boers as a Captain of the Grenadier Guards at Majuba Hill, Transvaal, in 1881. Before that, around 1870, the house was gutted and internally reconstructed.[2] In 1875, Maude-Fleming sold the Cumbernauld 'interesting historical estate' to John William Burns, son of James Burns of Bloomfield, for £160,000.[5] The house was gutted by fire on the evening of 16 March 1877.[6] The Burns family sold the estate to the government for the development of Cumbernauld new town in 1955.

The grounds of the House included a gamekeeper's cottage with a summerhouse, dovecote and kennels still shown on the 1864 map.[7] Everything except the dovecote was demolished. It is now a category B, listed building. A colour photo of the cottage survives.[8]

Groome's Gazetteer has "Cumbernauld House, standing amid an extensive park, ¼ mile ESE of the town, superseded an ancient castle, which, with its barony, passed about 1306 from the Comyns to Sir Robert Fleming, whose grandson, Sir Malcolm, was lord of both Biggar and Cumbernauld; it is now a seat of John William Burns, Esq. of Kilmahew (b. 1837; suc. 1871), owner of 1670 acres in the shire, valued at £3394 per annum. Other mansions are Dullatur House, Nether Croy, and Greenfaulds; and 4 proprietors hold each an annual value of £500 and upwards, 16 of between £100 and £500,12 of from £50 to £100, and 35 of from £20 to £50. Taking in quoad sacra a small portion of Falkirk parish, Cumbernauld is in the presbytery of Glasgow and synod of Glasgow and Ayr; the living is worth £380. Three public schools- Cumbernauld, Condorrat, and Arns-and Drumglass Church school, with respective accommodation for 350, 229,50, and 195 children, had (1880) an average attendance of 225,98,30, and 171, and grants of £230, 6s. 6d., £90,3s., £41,5s., and £162,8s. 6d. Valuation (1860) £15,204, (1882) £25,098,15s. Pop. (1801) 1795, (1831) 3080, (1861) 3513, (1871) 3602, (1881) 4270.—Ord. Sur., sh. 31,1867."

Following transfer of ownership to Cumbernauld Development Corporation, the first caretaker of Cumbernauld House was Stewart Law. Stewart Law was a Justice of the Peace, a correspondent for The Falkirk Herald, was on the Planning Committee for Cumbernauld New Town, and worked in the Architect's Office within Cumbernauld House. Stewart resided in Cumbernauld House with his wife, Helen Grant McGuire (b.01/06/1899 - d.12/02/1957), until his death in Glasgow Royal Infirmary on 4 November 1958 as a result of injuries sustained in a road traffic accident which had occurred in Cumbernauld Village four days earlier. He was 63 years old and left behind four sons, two daughters and twelve grandchildren.

Modern history

Cumbernauld HIT, a CDC sponsored comedy film from 1977, features the exterior and interior of the house. With hints of The Avengers and Taggart, it about an evil woman's plans to hijack the New Town of Cumbernauld with a bio-weapon.[9]

In January 2009 the Cumbernauld News reported that the Friends of Cumbernauld House had presented a case to the Scottish Government for the house to become a national museum of photography. One of the former residents of Cumbernauld House is reported to have been Lady Clementina Elphinstone-Fleming, a pioneer Victorian photographer. The articles goes on to note that the Scottish Government has stated there are no plans to buy the property.

In early 2010 a re-invigorated Facebook campaign was launched entitled 'Save and Preserve Cumbernauld House'.

Despite some local opposition, the House was subsequently developed into luxury apartments.

Conservation area

Cumbernauld House is not part of a historical conservation area running from the listed kirk and manse at Baronhill, through the Village conservation area with its Lang Riggs, to the site of Cumbernauld Castle and beyond that to the Comyn Motte and adjacent lime kilns. The whole represents the classic 'herringbone' layout of the mediaeval Scottish burgh with its principal street running from the castle to the church, along the summit of a ridge, with long narrow gardens (the Lang Riggs) stretching out behind. Cumbernauld village boasts almost the sole survivors of the land riggs feature in Scotland. From the slopes of the Wilderness Brae a panoramic view of the whole arrangement may be obtained - a view unique in Scotland: Edinburgh's Royal Mile in miniature. The wide centre of Main Street accommodated the stalls of the weekly market.

References

- "Cumbernauld House, Site Number NS77NE 16.00". CANMORE. Royal Commission on the Ancient and Historical Monuments of Scotland. Retrieved 2010-02-02.

- Historic Environment Scotland. "CUMBERNAULD HOUSE (Category A) (LB24086)". Retrieved 13 March 2019.

- Calendar State Papers Scotland, vol. (1898), no. 1071, p. 598.

- http://archiver.rootsweb.ancestry.com/th/read/LANARK/1999-02/0917901724 Mob 5000 strong

- The Book of Dunbartonshire; Irving, 1878

- https://archive.org/stream/bookdumbartonsh04irvigoog#page/n441/mode/1up Irvine - The Book of Dunbartonshire pg 396

- "Dumbarton Sheet XXVI.1 (Cumbernauld)". National Library of Scotland. Retrieved 10 August 2016.

- Smith, Adam (2015). Cumbernauld Through Time. Amberley Publishing. p. 29. ISBN 978 1 4456 4522 3.

- "CUMBERNAULD HIT". National Library of Scotland. Retrieved 2018-02-25.

- History of the Area, Cumbernauld Allotments Association

- Cumbernauld, Monklands Online

- "Days Gone By", Friends of Cumbernauld Glen

External links

- Cumbernauld House, sale particulars and background from King Sturge estate agents

- Cumbernauld House Park

- Photographs of the interior of the house