Criegee oxidation

The Criegee oxidation is a glycol cleavage reaction in which vicinal diols are oxidized to form ketones and aldehydes using lead tetraacetate. It is analogous to the Malaprade reaction, but uses a milder oxidant. This oxidation was discovered by Rudolf Criegee and coworkers and first reported in 1931 using ethylene glycol as the substrate.[1]

| Criegee oxidation | |

|---|---|

| Named after | Rudolf Criegee |

| Reaction type | Organic redox reaction |

| Identifiers | |

| RSC ontology ID | RXNO:0000257 |

The rate of the reaction is highly dependent on the relative geometric position of the two hydroxyl groups, so much so that diols that are cis on certain rings can be reacted selectively as opposed to those that are trans on them.[2] It was heavily stressed by Criegee that the reaction must be run in anhydrous solvents, as any water present would hydrolyze the lead tetraacetate; however, subsequent publications have reported that if the rate of oxidation is faster than the rate of hydrolysis, the cleavage can be run in wet solvents or even aqueous solutions.[3] For example, glucose, glycerol, mannitol, and xylose can all undergo a Criegee oxidation in aqueous solutions, but sucrose cannot.[4][5]

Mechanism

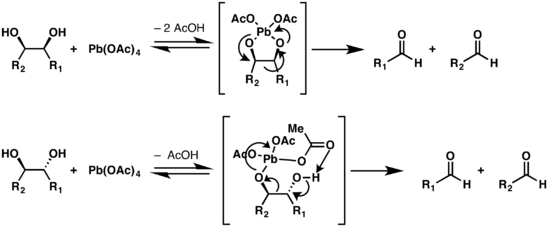

There are two mechanisms proposed for the Criegee oxidation which depend on the configuration of the diol.[6] If the oxygen atoms of the two hydroxy groups are conformationally close enough to form a five-membered ring with the lead atom, the reaction occurs via a cyclic intermediate. If the structure cannot adopt such a conformation, an alternate mechanism is possible, but is slower.[7] Trans-fused five member rings are heavily strained, thus trans-diols that are on a five-membered ring will react slower than cis-alcohols on such a structure.[8]

Modifications

Although the classic substrate for the Criegee oxidation are 1,2-diols, the oxidation can be employed with β-amino alcohols,[9] α-hydroxy carbonyls,[10] and α-keto acids,[11] In the case of β-amino alcohols, a free radical mechanism is proposed.

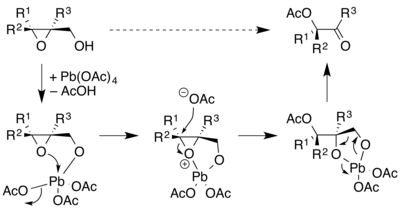

The Crigee oxidation can also be employed with 2,3-epoxy alcohols forms α-acetoxy carbonyls. Because the substrates can be produced with specific stereochemistry, such as by Sharpless epoxidation of allylic alcohols, this process can yield chiral molecules.[12]

Criegee oxidations are commonly used in carbohydrate chemistry to cleave 1,2-glycols and differentiate between different kinds of glycol groups.[13]

References

- Crieege, R. (1931). "Eine oxydative Spaltung von Glykolen". Berichte der deutschen chemischen Gesellschaft. 64: 260–266.

- Reeves, Richard E. (1949). "Direct Titration of cis-Glycols with Lead Tetraacetate". Analytical Chemistry. 21: 751. doi:10.1021/ac60030a035.

- Baer, Erich; Grosheintz, J. M.; Fischer, Hermann O. L. (1939). "Oxidation of 1,2-Glycols or 1,2,3-Polyalcohols by Means of Lead Tetraacetate in Aqueous Solution". Journal of the American Chemical Society. 61: 2607–2609. doi:10.1021/ja01265a010.

- Hockett, Robert C.; Zief, Morris (1950). "Lead Tetraacetate Oxidations in the Sugar Group. XI. The Oxidation of Sucrose and Preparation of Glycerol and Glycol". Journal of the American Chemical Society. 72: 2130–2132. doi:10.1021/ja01161a073.

- Abraham, Samuel (1950). "The Quantitative Recovery of Carbon Dioxide in Lead Tetraacetate Oxidations of Sugars and Sugar Derivatives". Journal of the American Chemical Society. 72: 4050–4053. doi:10.1021/ja01165a058.

- Criegee, Rudolf; Büchner, Eberhard; Walther, Werner (1940). "Die Geschwindigkeit der Glykolspaltung mit BleiIV-acetat in Abhängigkeit von der Konstitution des Glykols". Berichte der deutschen chemischen Gesellschaft. 73: 571–575. doi:10.1002/cber.19400730603.

- Mihailović, Mihailo Lj.; Čeković, Živorad; Mathes, Brian M. (2005). "Lead(IV) Acetate". e-EROS Encyclopedia of Reagents for Organic Synthesis. Elsevier. pp. 114–115. doi:10.1002/047084289X.rl006.pub2.

- László, Barbara, Kürti, Czakó (2005). Strategic Applications of Named Reactions in Organic Synthesis. Murlington, MA: Elsevier Academic Press. pp. 114–115. ISBN 978-0-12-429785-2.

- Leonard, Nelson J.; Rebenstorf, Melvin A. (1945). "Lead Tetraacetate Oxidation of Aminoalcohols". Journal of the American Chemical Society. 67: 49–51. doi:10.1021/ja01217a016.

- Evans, David A.; Bender, Steven L.; Morris, Joel (1988). "The total synthesis of the polyether antibiotic X-206". Journal of the American Chemical Society. 110: 2506–2526. doi:10.1021/ja00216a026.

- Baer, Erich (1942). "Oxidative Cleavage of Cyclic α-Keto Alcohols by Means of Lead Tetraacetate". Journal of the American Chemical Society. 64: 1416–1421. doi:10.1021/ja01258a049.

- Alvarez-Manzaneda, Enrique; Chahboun, Rachid; Alvarez, Esteban; Alvarez-Manzaneda, Ramón; Muñoz, Pedro E.; Jiménez, Fermín; Bouanou, Hanane (2011). "Lead(IV) acetate oxidative ring-opening of 2,3-epoxy primary alcohols: a new entry to optically active α-hydroxy carbonyl compounds". Tetrahedron Letters. 52: 4017-4020. doi:10.1016/j.tetlet.2011.05.116.

- Perlin, A. S. (1959). "Action of Lead Tetraacetate on the Sugars". Advances in Carbohydrate Chemistry. 14. p. 9-61. doi:10.1016/S0096-5332(08)60222-2.