Craniotabes

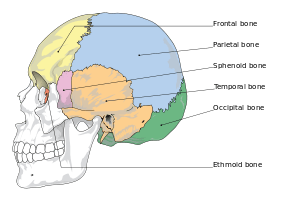

Craniotabes is softening or thinning of the skull in infants and children, which may be normally present in newborns. It is seen mostly in the occipital and parietal bones. The bones are soft, and when pressure is applied they will collapse underneath it. When the pressure is relieved, the bones will usually snap back into place.[1][2]

| Craniotabes | |

|---|---|

| |

| Cranial bones | |

| Specialty | Pediatrics |

Causes

Any condition that affects bone growth, most notably rickets[3][4] (from vitamin D deficiency),[5] marasmus, syphilis, or thalassemia, can cause craniotabes if present during a time of rapid skull growth (most especially during gestation and infancy). It can be a "normal" feature in premature infants. It is the first sign in children and infants with rickets.

Diagnosis

Physical examination

Management

Management of craniotabes depends on the cause. The majority of craniotabes occurs in term infants and can be a normal finding. Commonly, craniotabes results from the position of the head inside the uterus weeks prior to delivery. Calcium and Vitamin D levels should be obtained to rule out rickets, and in mothers who have prenatal labs concerning for T. pallidum infection, neonates should be evaluated for congenital syphilis.

Etymology

The term (cranio- + tabes) is derived from the Latin words cranium for skull and tabes for wasting.

References

- Harvey, Nicholas C.; Holroyd, Christopher; Ntani, Georgia; Javaid, Kassim; Cooper, Philip; Moon, Rebecca; Cole, Zoe; Tinati, Tannaze; Godfrey, Keith; Dennison, Elaine; Bishop, Nicholas J.; Baird, Janis; Cooper, Cyrus (2014). "Vitamin D supplementation in pregnancy: a systematic review". Health Technology Assessment (Winchester, England). 18 (45): 1–190. doi:10.3310/hta18450. ISSN 2046-4924. PMC 4124722. PMID 25025896.

- Prentice, Ann (July 2013). "Nutritional rickets around the world". The Journal of Steroid Biochemistry and Molecular Biology. 136: 201–206. doi:10.1016/j.jsbmb.2012.11.018. PMID 23220549.

- Elidrissy, Abdelwahab T. H. (31 May 2016). "The Return of Congenital Rickets, Are We Missing Occult Cases?". Calcified Tissue International. 99 (3): 227–236. doi:10.1007/s00223-016-0146-2. PMID 27245342.

- Paterson, Colin R.; Ayoub, David (October 2015). "Congenital rickets due to vitamin D deficiency in the mothers". Clinical Nutrition. 34 (5): 793–798. doi:10.1016/j.clnu.2014.12.006. PMID 25552383.

- Ercan, Makbule (2016). "Relationship between newborn craniotabes and vitamin D status". Northern Clinics of Istanbul. 3 (1): 15–21. doi:10.14744/nci.2016.48403. PMC 5175072. PMID 28058380.

External links

| Classification | |

|---|---|

| External resources |