Craigellachie Bridge

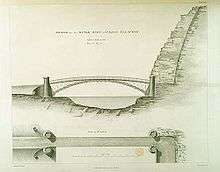

Craigellachie Bridge is a cast iron arch bridge across the River Spey at Craigellachie, near to the village of Aberlour in Moray, Scotland. It was designed by the renowned civil engineer Thomas Telford and built from 1812 to 1814. It is a Category A listed structure.[1]

Craigellachie Bridge | |

|---|---|

East elevation | |

| Coordinates | 57°29′27.15″N 3°11′37.23″W |

| Carries | Formerly carried |

| Crosses | River Spey |

| Locale | Craigellachie |

| Named for | Craigellachie |

| Owner | unknown |

| Maintained by | Moray Council |

| Heritage status | Category A listed |

| Characteristics | |

| Material | cast iron |

| Pier construction | granite |

| Total length | 46 m (151 ft) |

| Width | 5.4 m (18 ft) |

| Height | 10 m (33 ft) (max) |

| Traversable? | restricted to pedestrians/cycles |

| No. of lanes | one |

| Design life | Restored 1964 |

| History | |

| Constructed by | Thomas Telford |

| Fabrication by | William Hazledine Plas Kynaston iron works, Cefn Mawr, North Wales |

| Construction start | 1812 |

| Construction end | 1814 |

| Closed | 1972 (to road traffic) |

| Replaced by | reinforced concrete Beam bridge (1972) |

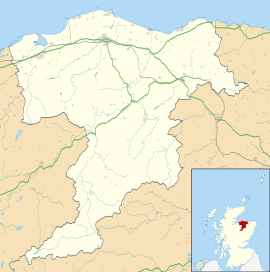

Location in Moray | |

Construction

The bridge has a single span of approximately 46 metres (151 ft) and was revolutionary for its time, in that it used an extremely slender arch which was not possible using traditional masonry construction. The ironwork was cast at the Plas Kynaston iron foundry at Cefn Mawr, near Ruabon in Denbighshire by William Hazledine, who cast a number of Telford bridges. The ironwork was transported from the foundry through the Ellesmere Canal and Pontcysyllte Aqueduct then by sea to Speymouth, where it was loaded onto wagons and taken to the site. Testing in the 1960s revealed that the cast-iron had an unusually high tensile strength. This was probably specified by Telford because, unlike in traditional masonry arch bridges, some sections of the arch are not in compression under loading.

At each end of the structure there are two 15 m (49 ft) high masonry mock-medieval towers, featuring arrow slits and miniature crenellated battlements.

History

The bridge was in regular use until 1963, when it was closed for a major refurbishment. A plaque records the completion of this work in 1964. The side railings and spandrel members were replaced with new ironwork fabricated to match the originals. A 14 ton restriction was placed on the bridge at this point. This, along with the fact that the road to the north of the bridge takes a sharp right-angled turn to avoid a rock face, made it unsuitable for modern vehicles. Despite this, it carried foot and vehicle traffic across the River Spey until 1972, when its function was replaced by a reinforced concrete beam bridge built by Sir William Arrol & Co. which opened in 1970 and carries the A941 road today. Telford's bridge remains in good condition, and is still open to pedestrians and cyclists. The bridge has been given Category A listed status by Historic Scotland and has been designated a civil engineering landmark by the Institution of Civil Engineers and American Society of Civil Engineers.[2]

In 1994, it hosted a parade upon the amalgamation of The Gordon Highlanders and The Queen's Own Highlanders (Seaforth and Camerons) to form The Highlanders (Seaforth, Gordons and Camerons). A plaque has been fitted to the bridge parapet to commemorate this.

Moray Council maintain the bridge, but it is not known who owns it. In November 2017 efforts were started to discover the owner.[3]

Usage in media

The bridge inspired Scottish composer William Marshall to write the popular Strathspey dance in 1814.

The bridge was commemorated on a Royal Mail postage stamp in 2015.[4]

It also features in the artwork and logos of Spey Valley Brewery who brew an 1814 lager in commemoration of the bridge.[5]

References

- Historic Environment Scotland. "Craigellachie, Old Bridge over River Spey (Telford Bridge) (Category A) (LB2357)". Retrieved 29 March 2019.

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 1 September 2013. Retrieved 21 August 2013.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- "Bid to trace owners of iconic Craigellachie Bridge". BBC NEWS. 10 November 2017.

- https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-scotland-north-east-orkney-shetland-31727530

- "1814 Spey Valley Lager". Spey Valley Brewery.

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Craigellachie Bridge. |

Bibliography

- Nelson, Gillian (1990). Highland Bridges. Aberdeen University Press. ISBN 0-08-037744-0.

- Paxton, Roland. "Thomas Telford's Cast-Iron Bridges". Proceedings of the Institution of Civil Engineers (Special Issue One ed.). 160. ISSN 0965-089X.