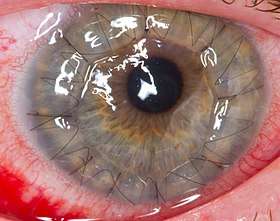

Corneal button

A corneal button is a replacement cornea to be transplanted in the place of a damaged or diseased cornea normally approximately 8.5–9.0mm in diameter.[1] It is used in a corneal transplantation procedure (also corneal grafting) whereby the whole, or part, of a cornea is replaced.[2] The donor tissue can now be held for days to even weeks of the donor’s death and is normally a small, rounded shape.[3] The main use of the corneal button is during procedures where the entirety of the cornea needs to be replaced, also known as penetrating keratoplasty.[2]

| Corneal button | |

|---|---|

Corneal button one day after surgery | |

| Specialty | ophthalmology |

History

Greek physician Galen is said to have first consider the possibility of corneal transplantation[4] however, there is no evidence that he actually attempted the procedure.[5] It was only until the 18th century that early surgical proposals for keratoplasty would arise and the 19th century for experimentation in the field to begin.[6]

In 1813, Karl Himley suggested that opaque animal corneas can be replaced by transplanting corneas from other animals; with his student Franz Reisenger commencing experimentation in 1818.[5]

In 1844, Edward Kissam undertook the first ever recorded attempt of a xenograft on a human; the donor was a pig and was ultimately unsuccessful.[6] Henry Power made a suggestion in 1867 that using human tissue rather than animal tissue for transplantation would be more effective however, it would not be until 1905 for the first successful human corneal transplant by MD, Eduard Zirm.[6]

Since 1905, various techniques and procedures have been developed to increase the effect of the transplantation and success rate. Traditionally, the most common procedure for corneal transplantation was penetrating keratoplasty whereby an entire corneal button is replaced.[6] Recently however, procedures such as anterior and posterior lamellar techniques where only diseased or damaged layers of the cornea are selectively replaced have become increasingly popular.[6]

Procedure

After the death of the donor, the cornea must be retrieved within a few hours and will be screened for diseases and assessed for its viability to be used for a corneal transplantation by assessing its health. If passed, the cornea will be stored in a nutrient solution at an eye bank until needed for an operation.[1] In most cases, the corneal button is removed from the donor cornea prior to storage as this extends its possible storage time.[3]

For the operation procedure, the patient is anaesthetised and the damaged or diseased corneal button will be removed using a bladed instrument called a trephine (approximately 8.0–8.5mm in diameter).[7] A corneal button of matching size is then put in place of the removed tissue and stitched in place. Usually, twelve clock-hour nylon stitches are used with a continuous band nylon stitch.[1]

The procedure takes approximately 60–90 minutes however, a few months will be required for vision to return to what it was like preceding the operation; and continue to improve from then on. Approximately 12–18 months after the operation, all stitches will be removed. During this time, anti-rejection drops will be needed to minimise inflammation; the dosage of which is carefully monitored by a corneal surgeon.[1]

Due to the swelling, it is impossible to predict the quality of vision without removing the stitches. A few months after the stitches are removed, measurements are made of the shape of the cornea and refractive error. If the shape of the cornea is fairly regular and refractive error is similar to that of the other eye, it is usually possible to fix any error with glasses; if not, a hard lens may be necessary to correct vision.[1]

Corneal graft rejection

One of the largest causes for issue in penetrating keratoplasty is the natural immune rejection of a transplanted corneal button which can cause reversible or irreversible damage to the grafted cornea. The types corneal rejection include epithelial rejection, chronic rejection, hyperacute rejection and endothelial rejection and these can occur individually, or in some cases in conjunction.[8]

There are however, two main preventative methods to reduce the possibility of immune rejection; prevention and management. Prevention involves increasing compatibility of the donor tissue with that of the patient and suppressing host immune response. These analyses of donor corneas are done during a screening phase soon after receiving the donation. The management aspect mainly involves early detection and therapy with corticosteroids along with Immunosuppressive therapy.[8]

Corneal button storage

There are two main storage methods used in the storage of the corneal button. They are stored using a hypothermic storage method or an organ culture method in a tissue culture medium. Corneal buttons cannot be reliably frozen as a storage method.[3]

Usually, the corneal button is removed from the entire globe before storage as this extends the possible storage time.[3]

The hypothermic storage method was first introduced in 1974[9] and it requires no complex equipment. It is stored in a refrigerator, usually 2–6 °C, in commercially available storage solutions. Factors such as the temperature, maximal storage time, expiry date, etc. should be maintained according to the storage solution manufacturer’s recommendations and can vary depending on the solution. Also, provided donor screening permits are available, the corneal tissue can be used immediately after leaving storage for surgery. Inspection of tissue can however be performed in a closed system under a slit lamp or secular microscope.[3]

The organ culture method, first introduced in 1976,[10] is however quite complicated. The corneal button is stored in an incubator approximately 30–37 °C in a tissue culture medium into which either fetal or new-born calf serum, antibiotics and antimycotics are added. The corneal cells are also injected with dehydrating macromolecules to maintain hydration, this causes the corneal button to swell to approximately twice its original thickness during storage. During storage, the medium must be replaced within every 10–14 days. When it is required for surgery, the swollen tissue is placed in a dextrin containing storage medium which brings down the swelling and must also be inspected under strict aseptic conditions.[3]

Donor selection

There is a rigorous criteria for donor selection as it is essential to minimise possibility of disease transmission. This criteria focuses on medial medical records and post-mortem serological tests which aim not to eliminate risk, but to limit risk to a reasonable level. A balance between safety and availability.[11]

A health history report is usually used however, death certificate reports and data from family and acquaintances are also acceptable substitutions. The donation is rejected if no information can be found.[11]

Donations can be rejected or limited if some specific diseases are found in a donor's medical history. Diseases transmissible via corneal transplantation include bacterial infection and fungal infection,[12] rabies,[13] Hepatitis B[14] and retinoblastoma.[15] Diseases likely to be transmissible via corneal transplantations include HIV, Herpes simplex virus and Prion disease.[16] There are also many other diseases which may result in rejection of donations.[16]

References

- Keratoconus Australia. (n.d.). Corneal transplantation. Retrieved from https://www.keratoconus.org.au/treatments/corneal-transplantation/

- National Keratoconus Foundation. (2018). About Corneal Transplant Surgery. Retrieved from https://www.nkcf.org/about-corneal-transplant-surgery/

- Elisabeth, P., Hilde, B., & Ilse, C. (2008). Eye bank issues: II. Preservation techniques: warm versus cold storage. International Ophthalmology, 28(3), 155–163. doi:10.1007/s10792-007-9086-1

- Moffatt, S. L., Cartwright, V. A., & Stumpf, T. H. (2005). Centennial review of corneal transplantation. Clinical & Experimental Ophthalmology, 33(6), 642–657. doi:10.1111/j.1442-9071.2005.01134.x

- Anastas, C. N., McGhee, C. N., Webber, S. K. and Bryce, I. G. (1995). Corneal tattooing revisited: excirner laser in the treatment of unsightly leucornata. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Ophthalmology, 23: 227–230. doi:10.1111/j.1442-9071.1995.tb00163.x

- Crawford, A. Z., Patel, D. V., & McGhee, C. N. (2013). A brief history of corneal transplantation: From ancient to modern. Oman Journal of Ophthalmology, 6(Suppl 1), S12–S17. doi:10.4103/0974-620X.122289

- Wachler, B. S. B. (2017). Cornea Transplants: What to Expect. Retrieved from https://www.allaboutvision.com/conditions/cornea-transplant.htm

- Panda, A., Vanathi, M., Kumar, A., Dash, Y., & Priya, S. (2007). Corneal graft rejection. Survey of Ophthalmology, 52(4), 375–396. doi:10.1016/j.survophthal.2007.04.008

- McCarey, B. E., Kaufman, H. E. (1974). Improved Corneal Storage. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci, 13(3), 165–173. Retrieved from https://iovs.arvojournals.org/article.aspx?articleid=2158398

- Doughman, D. J., Harris, J. E., & Schmitt, M. K. (1976). Penetrating keratoplasty using 37 C organ cultured cornea. Transactions of the American Academy of Ophthalmology and Otolaryngology, 81(5), 778–793. PMID 798366. Retrieved from www.scopus.com

- Júlio, S., & Barretto, S. (2017). Eye bank procedures: donor selection criteria. Arq Bras Oftalmol, 81(1), 73–79. doi:10.5935/0004-2749.20180017

- Gandhi, S. S., Lamberts, D. W., & Perry, H. D. (1981). Donor to host transmission of disease via corneal transplantation. Survey of Ophthalmology, 25(5), 306–310. doi:10.1016/0039-6257(81)90156-9

- Lu, X.-X., Zhu, W.-Y., & Wu, G.-Z. (2018). Rabies virus transmission via solid organs or tissue allotransplantation. Infectious Diseases of Poverty, 7, 82. doi:10.1186/s40249-018-0467-7

- Hoft, R. H., Pflugfelder, S. C., Forster, R. K., Ullman, S., Polack, F. M., & Schliff, E. R. (1997). Clinical evidence for hepatitis B transmission resulting from corneal transplantation. Cornea, 16(2), 132–137. PMID 9071524.

- Urbańska, K., Sokołowska, J., Szmidt, M., & Sysa, P. (2014). Glioblastoma multiforme – an overview. Contemporary Oncology, 18(5), 307–312. doi:10.5114/wo.2014.40559

- Liaboe, C., Vislisel, J. M., Schmidt, G. A., & Greiner, M. A. (2015). Corneal Transplantation: From Donor to Recipient. Retrieved from http://EyeRounds.org/tutorials/cornea-transplant-donor-to-recipient