Copenhagenization

Copenhagenization is a term coined in the early 19th century, and has had occasional use since. It alludes to the Bombardment of Copenhagen in 1807, during the Napoleonic Wars.[1]

Background

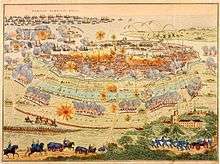

In 1807 Britain was at war with France, and the Emperor Napoleon had created an embargo, known as the Continental System, to strike at Britain's trade. Denmark was neutral in the war, but was believed to be leaning towards joining the embargo; also, her sizeable navy and geographic position at the entrance to the Baltic, commanding Britain's trade route with her ally, Sweden. In August 1807 Britain chose to attack Denmark, landing an army on Zealand which invested Copenhagen and commenced bombarding the city. Denmark was forced to capitulate and surrender her fleet: After the British withdrawal Denmark joined in an alliance with France against Britain and Sweden, but without a fleet she had little to offer.[2]. The brutal action, bombarding a city of civilians without a declaration of war, shocked other neutral nations, including the United States, which had her own issues with the United Kingdom.

First use of the term

The term "Copenhagenization" first appeared in an article in the Philadelphia Aurora in February 1808, which suggested British spies had traduced Denmark and would do so in America also: 'Her spies and agents here are pursuing the same course and expect the same consequences. Our cities will be Copenhagenized — and our ships, timber, treasury, etc. will be amicably deposited in Great Britain'[3]

In April William Cobbett made a robust response in his weekly Political Register: 'Oh, that example of Copenhagen has worked wonders in the world ! It will save a deal of strife, war, and bloodshed. I (would) like to see the name of that city become a verb in the American dictionary. "Our cities will be copenhagenized" is an excellent phrase. It's very true, that Sir John Warren would copenhagenize New York with very little trouble…'[4]

Further uses

The term "Copenhagenization" appeared in several US sources during the 19th century. In 1830, the American author Richard Emmons published an Epic poem on the late war of 1812, The Fredoniad, or Independence preserved[5] in which he wrote of the merits and risks of independence:

Aw'd by the naval sceptre of the king—

Our fleet would Copenhagenize each town,

And with the torch burn every hamlet down.

The term was later used by Justin Winsor in his Narrative and critical history of America (1888) where he described the outfitting of independent vessels to warfare being done somewhat covertly, in order to avoid the vessels being "Copenhagenized at once by the invincible British Navy"[6] at the outbreak of hostilities.

In the 1881 Political Science, Political Economy, and the Political History of the United States, John J. Lalor, editor, wrote:

But, even when the [embargo] was repealed in 1809, the belief that Great Britain would "Copenhagenize" any American navy which might be formed was sufficient to deter the democratic leaders from anything bolder than non-intercourse laws, until the idea of invading Canada took root and blossomed into a declaration of war.[7]

In 1993 Azar Gat, in War In Human Civilization, used the term twice, referring to "Britain's reluctance to copenhagenize the German Navy" prior to the First World War, and again that "the fall of France led the British to copenhagenize the French Navy" of neutral Vichy with the attack on Mers-el-Kébir.[8]

Explanation

The term "Copenhagenization" is best seen as a type of shorthand used by historians, by making comparison to a distinct and well-known incident. For example, a writer could describe an army as seeking to "do a Cannae",[9] or say that a navy was "Trafalgared",[10] in order to avoid a lengthy description.

However, the bombardment of Copenhagen is of less value in this regard, as Copenhagen was the scene of another battle six years earlier, when under similar circumstances the British navy attacked the Danish fleet at anchor and destroyed it.

Although the writer in the Aurora in 1808, and Emmons in 1830, were clear enough in referring to the 1807 incident, it is less clear which was meant by Lalor and Winsor, while the modern uses by Azar Gat are better understood as references to the events of 1801.

References

- The term is not recorded in either the Merriam-Webster or the Oxford English Dictionaries

- A. N. Ryan, "The Causes of the British Attack upon Copenhagen in 1807." English Historical Review (1953): 37–55. in JSTOR

- Cobbett’s Weekly Political Register, 9 April 1808 p.4

- Cobbett’s Weekly Political Register, 9 April 1808 p.6

- Emmons, Richard (1830). The fredoniad, or Independence preserved. Philadelphia. p. 35.

- Winsor, Justin (1884). Narrative and critical history of America. 7. Boston: Houghton, Mifflin and Company. pp. 273–274.

- Cyclopædia of Political Science, Political Economy, and the Political History of the United States by the Best American and European Writers: Maynard, Merrill, and Co. (1899) II.18.13 and II.18.26.

- Gat, Azar (2006). War In Human Civilization. New York: Oxford University Press. p. 610. ISBN 978-0-1992-3663-3.

- H Borowski, Military Planning in the Twentieth Century ( 1986 ) ISBN 9781428993433 p98

- John Keegan, The Price of Admiralty (2011) ISBN 9781446494509 p