Contract curve

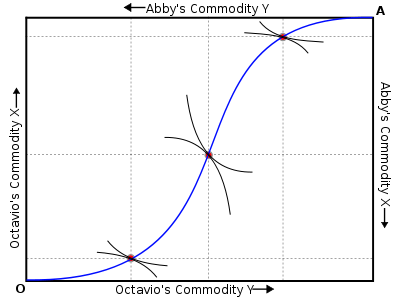

In microeconomics, the contract curve is the set of points representing final allocations of two goods between two people that could occur as a result of mutually beneficial trading between those people given their initial allocations of the goods. All the points on this locus are Pareto efficient allocations, meaning that from any one of these points there is no reallocation that could make one of the people more satisfied with his or her allocation without making the other person less satisfied. The contract curve is the subset of the Pareto efficient points that could be reached by trading from the people's initial holdings of the two goods. It is drawn in the Edgeworth box diagram shown here, in which each person's allocation is measured vertically for one good and horizontally for the other good from that person's origin (point of zero allocation of both goods); one person's origin is the lower left corner of the Edgeworth box, and the other person's origin is the upper right corner of the box. The people's initial endowments (starting allocations of the two goods) are represented by a point in the diagram; the two people will trade goods with each other until no further mutually beneficial trades are possible. The set of points that it is conceptually possible for them to stop at are the points on the contract curve. However, some authors[1] identify the contract curve as the entire Pareto efficient locus from one origin to the other.

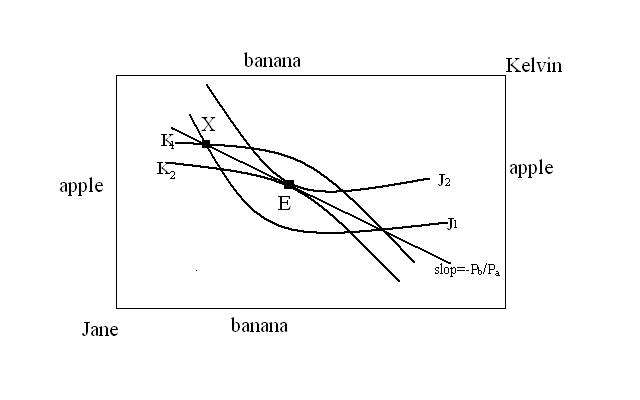

In the graph below, the initial endowments of the two people are at point X, on Kelvin's indifference curve K1 and Jane's indifference curve J1. From there they could agree to a mutually beneficial trade to anywhere in the lens formed by these indifference curves. But the only points from which no mutually beneficial trade exists are the points of tangency between the two people's indifference curves, such as point E. The contract curve is the set of these indifference curve tangencies within the lens—it is a curve that slopes upward to the right and goes through point E.

Any Walrasian equilibrium lies on the contract curve. As with all points that are Pareto efficient, each point on the contract curve is a point of tangency between an indifference curve of one person and an indifference curve of the other person. Thus, on the contract curve the marginal rate of substitution is the same for both people.

Example

Assume the existence of an economy with two agents, Octavio and Abby, who consume two goods X and Y of which there are fixed supplies, as illustrated in the above Edgeworth box diagram. Further, assume an initial distribution (endowment) of the goods between Octavio and Abby and let each have normally structured (convex) preferences represented by indifference curves that are convex toward the people's respective origins. If the initial allocation is not at a point of tangency between an indifference curve of Octavio and one of Abby, then that initial allocation must be at a point where an indifference curve of Octavio crosses one of Abby. These two indifference curves form a lens shape, with the initial allocation at one of the two corners of the lens. Octavio and Abby will choose to make mutually beneficial trades — that is, they will trade to a point that is on a better (farther from the origin) indifference curve for both. Such a point will be in the interior of the lens, and the rate at which one good will be traded for the other will be between the marginal rate of substitution of Octavio and that of Abby. Since the trades will always provide each person with more of one good and less of the other, trading results in movement upward and to the left, or downward and to the right, in the diagram.

The two people will continue to trade so long as each one's marginal rate of substitution (the absolute value of the slope of the person's indifference curve at that point) differs from that of the other person at the current allocation (in which case there will be a mutually acceptable trading ratio of one good for the other, between the different marginal rates of substitution). At a point where Octavio's marginal rate of substitution equals Abby's marginal rate of substitution, no more mutually beneficial exchange is possible. This point is called a Pareto efficient equilibrium. In the Edgeworth box, it is a point at which Octavio's indifference curve is tangent to Abby's indifference curve, and it is inside the lens formed by their initial allocations.

Thus the contract curve, the set of points Octavio and Abby could end up at, is the section of the Pareto efficient locus that is in the interior of the lens formed by the initial allocations. The analysis cannot say which particular point along the contract curve they will end up at — this depends on the two people's bargaining skills.

Mathematical explanation

In the case of two goods and two individuals, the contract curve can be found as follows. Here refers to the final amount of good 2 allocated to person 1, etc., and refer to the final levels of utility experienced by person 1 and person 2 respectively, refers to the level of utility that person 2 would receive from the initial allocation without trading at all, and and refer to the fixed total quantities available of goods 1 and 2 respectively.

subject to:

This optimization problem states that the goods are to be allocated between the two people in such a way that no more than the available amount of each good is allocated to the two people combined, and the first person's utility is to be as high as possible while making the second person's utility no lower than at the initial allocation (so the second person would not refuse to trade from the initial allocation to the point found); this formulation of the problem finds a Pareto efficient point on the lens, as far as possible from person 1's origin. This is the point that would be achieved if person 1 had all the bargaining power. (In fact, in order to create at least a slight incentive for person 2 to agree to trade to the identified point, the point would have to be slightly inside the lens.)

In order to trace out the entire contract curve, the above optimization problem can be modified as follows. Maximize a weighted average of the utilities of persons 1 and 2, with weights b and 1 – b, subject to the constraints that the allocations of each good not exceed its supply and subject to the constraints that both people's utilities be at least as great as their utilities at the initial endowments:

subject to:

where is the utility that person 1 would experience in the absence of trading away from the initial endowment. By varying the weighting parameter b, one can trace out the entire contract curve: If b = 1 the problem is the same as the previous problem, and it identifies an efficient point at one edge of the lens formed by the indifference curves of the initial endowment; if b = 0 all the weight is on person 2's utility instead of person 1's, and so the optimization identifies the efficient point on the other edge of the lens. As b varies smoothly between these two extremes, all the in-between points on the contract curve are traced out.

Note that the above optimizations are not ones that the two people would actually engage in, either explicitly or implicitly. Instead, these optimizations are simply a way for the economist to identify points on the contract curve.

See also

- Welfare economics

- List of economics topics

References

- Varian, Hal R. Microeconomic analysis, third edition, 1992, page 324.

- Mas-Colell, Andreu; Whinston, Michael D.; & Green, Jerry (1995). Microeconomic Theory. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-510268-1