Continuous foam separation

Continuous foam separation is a chemical process closely related to foam fractionation in which foam is used to separate components of a solution when they differ in surface activity. In any solution, surface active components tend to adsorb to gas-liquid interfaces while surface inactive components stay within the bulk solution. When a solution is foamed, the most surface active components collect in the foam and the foam can be easily extracted. This process is commonly used in large-scale projects such as water waste treatment due to a continuous gas flow in the solution.

There are two types of foam that can form from this process. They are wet foam (or kugelschaum) and dry foam (or polyederschaum). Wet foam tends to form at the lower portion of the foam column, while dry foam tends to form at the upper portion. The wet foam is more spherical and viscous, and the dry foam tends to be larger in diameter and less viscous.[1] Wet foam forms closer to the originating liquid, while dry foam develops at the outer boundaries. As such, what most people usually understand as foam is actually only dry foam.

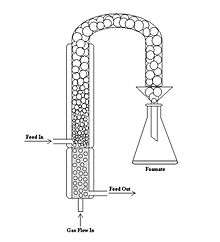

The setup for continuous foam separation consists of securing a column at the top of the container of solution that is to be foamed. Air or a specific gas is dispersed in the solution through a sparger. A collecting column at the top collects the foam being produced. The foam is then collected and collapsed in another container.

In the continuous foam separation process a continuous gas line is fed into the solution, therefore causing continuous foaming to occur. Continuous foam separation may not be as efficient in separating solutes as opposed to separating a fixed amount of solution.

History

Processes similar to continuous foam separation have been commonly used for decades. Protein skimmers are one example of foam separation used in saltwater aquariums. The earliest documents pertaining to foam separation is dated back to 1959, when Robert Schnepf and Elmer Gaden, Jr. studied the effects of pH and concentration on the separation of bovine serum albumin from solution.[2] A different study performed by R.B. Grieves and R. K. Woods[3] in 1964 focused on the various effects of separation based on the changes of certain variables (i.e. temperature, position of feed introduction, etc.). In 1965, Robert Lemlich[4] of the University of Cincinnati made another study on foam fractionation. Lemlich researched the science behind foam fractionation through theory and equations.

As stated earlier, continuous foam separation is closely related to foam fractionation where hydrophobic solutes attach to the surfaces of bubbles and rise to form foam. Foam fractionation is used on a smaller scale whereas continuous foam separation is implemented on a larger scale such as water treatment for a city. An article published by the Water Environment Federation[5] in 1969, discussed the idea of using foam fractionation to treat pollution in rivers and other water resources in cities. Since then, little research has been done to further understand this process. There are still many studies that implement this process for their research, such as the separation of biomolecules in the medical field.

Background

Surface chemistry

Continuous foam separation is dependent on the contaminant’s ability to adsorb to the surface of the solvent based on their chemical potentials. If the chemical potentials promote surface adsorption, the contaminant will move from the bulk of the solvent and form a film at the surface of the foam bubble. The resulting film is considered a monolayer.

As contaminants', or surfactants', concentration in the bulk decreases, the surface concentration increases; this increases surface tension at the liquid-vapor interface. Surface tension describes how difficult it is to extend the area of a surface. If surface tension is high, there is a large free energy required to increase the surface area. The surface of the bubbles will contract due to this increased surface tension. This contraction encourages the formation of a foam.

Foams

Definition

Foam is a type of colloidal dispersion where gas is dispersed throughout a liquid phase. The liquid phase is also called the continuous phase because it is an uninterrupted, unlike the gas phase.[1]

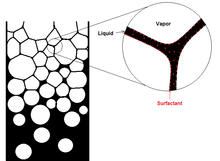

Structure

As the foam is formed, it changes in structure. As the liquid foams up into the gas, the foam bubbles begin as packed uniform spheres. This phase is the wet phase. The farther up the column the foam travels, the air bubbles distort to form polyhedral shapes, the dry phase. The liquid that separates the flat faces between two polyhedral bubbles is called the lamellae; it is a continuous liquid phase. The areas where three lamellae meet are called plateau borders. When the bubbles in the foam are the same size the lamellae in the plateau borders meet at 120 degree angles. Since the lamella is slightly curved, the plateau region is at low pressure. The continuous liquid phase is held to the bubble surfaces by the surfactant molecules that make up the solution being foamed. This fixation is important because otherwise the foam becomes very unstable as the liquid drains into the plateau region making the lamellae thin. Once the lamellae become too thin they will rupture.[6]

Theory

Young-Laplace equation

As vapor bubbles form in a liquid solvent, interfacial tension causes a pressure difference, Δp, across the surface given by the Young-Laplace equation. The pressure is greater on the concave side of the liquid lamellae (the inside of the bubble) with radius, R, dependent on the pressure differential. For spherical bubbles in a wet foam and standard surface tension γ°, the equation for the change in pressure is as follows:

As the vapor bubbles distort and take the form of a more complex geometry than a simple sphere, the two principal radii of curvature R1 and R2 would be used in the following equation:[1]

As pressure grows inside the bubbles, the liquid lamellae shown in the figure above will forced to move toward plateau borders causing a collapse of the lamellae.

Gibbs adsorption isotherm

The Gibbs adsorption isotherm can be used to determine the change in surface tension with changing concentration. Since chemical potential varies with a change in concentration, the following equation can be used to estimate the change in surface tension where dγ is the change in surface tension of the interface, Γ1 is the surface excess of the solvent, Γ2 is the surface excess of the solute (surfactant), dμ1 is the change in chemical potential of the solvent, and dμ2 is the change in chemical potential of the solute:[7]

For ideal cases, Γ1=0 and the created foam is dependent on the change in chemical potential of the solute. During foaming, the solute experiences a change in chemical potential as it goes from the bulk solution to the foam surface. In this case, the following equation can be applied where a is the activity of the surfactant, R is the gas constant, and T is the absolute temperature:

In order solve for the area on the foam surface occupied by one adsorbed molecule, As, the following equation can be used where NA is Avogadro's number.

Applications

Wastewater treatment

Continuous foam separation is used in wastewater treatment to remove detergent-derived foaming agents such as ABS, which became common in wastewater by the 1950s.[8] In 1959 it was shown that by adding 2-octane to foamed wastewater, 94% of ABS could be removed from the activated sludge through using foam separation techniques.[9] The foam produced during wastewater treatment can either be recycled back into the activated sludge tank within a waste treatment plant, the bacterial organisms that live there have been found to break down ABS when allowed enough time, or extracted and collapsed for disposal.[10] Foam separation has also been found to decrease the chemical oxygen demand when used as secondary treatment technique for wastewater.[11]

Heavy metal removal

The removal of heavy metal ions from wastewater is important because they accumulate easily in the food chain, ending in animals such as swordfish that humans eat. Foam separation can be used to remove heavy metal ions from wastewater at low costs, especially when used in multistage systems. When performing ion foam separation there are three operational conditions that must be met for optimal production of foam for ion removal: foam formation, flooding, and weeping/dumping.[12]

Protein extraction

Foam separation can be used for the extraction of proteins from a solution especially to concentrate the protein from a dilute solution. When purifying proteins from solution on an industrial scale, the most cost efficient method is desired. As such, foam separation offers a method with low capital and maintenance costs due to the simple mechanical design; this design also allows for easy operation.[13] However, there are two reasons why using foam separation to extract protein from solution has not been widespread: firstly some proteins denature when going through the foaming process and secondly, control and prediction of foaming is typically difficult to calculate. In order to determine the success of protein extraction through foaming three calculations are used.[14]

The Enrichment ratio demonstrates how effective the foaming is in extracting the protein from the solution into the foam, the higher the number the better the affinity the protein has for the foam state.

The Separation ratio is similar to the enrichment ratio in that the more effective the extraction of protein from the solution into the foam, the higher the number will be.

Recovery is how efficiently the protein is removed from the solution into the foam state, the higher the percentage, the better the process is at recovering protein from solute into the foam state.

Foam hydrodynamics as well as many of the variables that affect the success of foaming have limited understanding. This complicates using mathematical calculations to predict protein recovery by foaming. However some trends have been determined; high recovery rates have been linked to high concentrations of protein in the initial solution, high gas flow rates, and high feed flow rates. Enrichment is also known to increase when foaming is performed using shallow pools. Using pools with low heights allows for only a small amount of protein to adsorb from the solution to the surface of the bubbles in the foam resulting in lower surface viscosity. This leads to coalescence of the unstable foam higher up in the column causing an increase in the bubble size and an increase in the reflux of the protein in the foam. However, an increased velocity of the gas being pumped into the system has been shown to lead to a decrease in the enrichment ratio.[15] Since these calculations are difficult to predict, bench and then pilot scale experiments are often performed in order to determine if foaming is a viable technique for extraction on an industrial scale.

Bacterial cell extraction

Separation of cells is typically done using centrifugation, however foam separation has also been used as a more energy efficient technique. This method has been used on many species of bacteria cells such as Hansenula polymorph, Saccharomyces carlsbergensis, Bacillus polymyxa, Escherichia coli, and Bacillus subtilis, being most effective on cells that have hydrophobic surfaces.[16]

Current and Future Directions

Continuous foam extraction was initially used in regard to wastewater treatment in the 1960s. Since then there has not been a lot of research in foaming as an extraction technique. However, in recent years foaming for protein and pharmaceutical extraction has gained increased interest for researchers. Purification of products is the most expensive part of product production in biotechnology, foaming offers an alternative method that is less expensive than some current techniques.

Separation equipment

Foaming apparatus

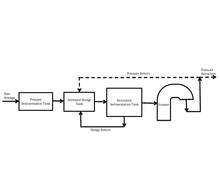

Continuous foam separation is one of two major modes of foam separation with the other being batch foam separation. The difference between the two modes is that in continuous mode, surfactant solution is continuously fed through a feed into the foam column and a solution, extracted of surfactant, is also continuously exiting the bottom of the apparatus. The figure to the right shows a diagram of a basic continuous foam separator. The process is stationary (or in steady state) as long as the volume of liquid is constant as a function of time. As long as the process is in steady state, the liquid will not overflow into the foaming column. Depending on the design of the foam separator, the location of the feed flowing in can vary from atop of the liquid solution to the top of the foam column.[17]

The creation of the foam starts with the flow of gas into the bottom of the liquid column. The amount of gas flow into the apparatus is measured and maintained through a flow meter. As the foam rises and becomes drained of the liquid, it gets diverted into a separate container to collect the foamate. The height of the foam column is dependent on the application. The diverted foam is liquefied by collapsing the foam bubbles. This can usually be achieved by mechanical means or by lowering the pressure in the foamate collecting vessel. Foam separators for different types of applications use the basic set up shown in the diagram, but can vary with placements and addition of equipment.

Design considerations

Additional equipment on the basic form of a foam separator apparatus can be used to achieve other desired effects that suit the type of application, but the underlying process of separation remains the same. The addition of equipment is used to optimize the parameters, enrichment E, or recovery R. Typically, enrichment and recovery are opposing parameters, but there have been some recent studies showing the ability to simultaneously optimize both parameters.[17] The variation of flow rates on the gas input as well as other equipment settings has effects on the optimization of the parameters. The table compares foam separation to other techniques used to separate the protein, α-lactalbumin, from a whey protein solution.

| Foam Separation (Semi-Batch)[18] | Foam Separation (Batch)[19] | Cation-Exchange Chromotography[20] | Ultrafiltration (CC-DC mode)[21] | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Recovery (%) | 86.2[18] | 64.5[19] | 90[20] | 80[21] |

| Feed/Initial Concentration (mg/mL) | 0.075[18] | 0.49[19] | 0.72[20] | 1.75[21] |

| Starting Volume (mL) | 145[18] | - | - | - |

| Gas Flow Rate (mL/min) | 2.7[18] | 20[19] | - | - |

| Column Volume (mL)[20] | - | - | 80[20] | - |

| Buffer (mM)[20] | - | - | 100[20] | - |

| Membrane Area (m2)[21] | - | - | - | 0.045[21] |

| Permeation Flux (m2/h)[21] | - | - | - | 70[21] |

| pH Value | 4.9[18] | 2[19] | 4[20] | 7[21] |

pH

pH is an important factor in foaming because it will determine if a surfactant will be able to move into the foam phase from bulk liquid phase. The isoelectric point is one factor that must be taken into consideration, when surfactants have neutral charges they are more favorable for adsorption to the liquid-gas interface. pH offers a unique problem for proteins due to the fact that they will denature in pHs that are too high or low. While the isoelectric point is ideal for surfactant adsorption, it has been found that foam is most stable at a pH of 4 and that the foam volume is maximized at pH 10.[17]

Surfactants

The chain length of non polar parts of surfactants will determine how easily the molecules can adsorb to the foam, and will therefore determine how effective the separation of the surfactant from the solution will be. Longer chains surfactants tend to associate into micelles at the solid-liquid surface. The concentration of the surfactant also plays a factor in the percent removal of the surfactant.[6]

Other

Some other factors that affect the effectiveness of foaming include the flow rate of the gas, the bubble size and distribution, the temperature of the solution, and the agitation of the solution.[6] Detergents are known to affect foaming. They increase the ability of the solution to foam, increasing the amount of protein recovered in the foamate. Some detergents act as stabilizers for the foam, such as cetyltrimethylammonium bromide (CTAB).[17]

References

- [Schramm, Laurier L., and Fred Wassmuth. "Foams: Basic Principles." In Foams: Fundamentals and Applications in the Petroleum Industry. Petroleum Recovery Institute, 15 Oct. 1994. Web. 23 May 2012. <http://people.ucalgary.ca/~schramm/book4.htm>.].

- Grieves, R.B.; Wood, R.K. (1964). "Continuous foam fractionation: The effect of operating variables on separation". AIChE Journal. 10 (4): 1–11. doi:10.1002/jbmte.390010102.

- Schnepf, R.W.; Gaden, E.L. (1959). "Foam fractionation of proteins: Concentration of aqueous solutions of bovine serum albumin". Journal of Biochemical and Microbiological Technology and Engineering. 1 (1): 456–460. doi:10.1002/aic.690100409.

- Leonard, R.A.; Lemlich, R. (1965). "A study of interstitial liquid flow in foam. Part I. Theoretical model and application to foam fractionation". AIChE Journal. 11 (1): 18–25. doi:10.1002/aic.690110108.

- Stander, G. J.; Van Vuuren, L. R. J. (1969). "The Reclamation of Potable Water from Wastewater". Journal (Water Pollution Control Federation). 41 (3): 355–367. JSTOR 25036271.

- Arzhavitina, A.; Steckel, H. (2010). "Foams for pharmaceutical and cosmetic application". International Journal of Pharmaceutics. 394 (1–2): 1–17. doi:10.1016/j.ijpharm.2010.04.028. PMID 20434532.

- [Butt, Hans-Jürgen, Karlheinz Graf, and Michael Kappl. Physics and Chemistry of Interfaces. Weinheim: WILEY-VCH, 2010. Print.].

- Polkowski, L. B.; Rohlich, G. A.; Simpson, J. R. (September 1859). "Evaluation of Frothing in Sewage Treatment Plants". Sew. And Ind. Wastes. 31 (9): 1004. JSTOR 25033967.

- McGauhey, P. H., Klein, S. A., and Palmer, P. B., "A Study of Operating Variables as They Affect ABS Removal by Sewage Treatment Plants." Sanitary Engineering Research Lab., Univ. of California, Berkeley, Calif. (Oct. 1959).,

- Jenkins, David (Nov 1966). "Application of Foam Fractionation to Wastewater Treatment". Water Pollution Control Federation. 38 (11): 1737–1766. JSTOR 25035669.

- Grieves, Robert B.; Bhattacharyya, Dibakar (July 1965). "The foam separation process: A model for waste treatment applications". Water Pollution Control Federation. 37 (7): 980–989. JSTOR 25035325.

- Rujirawanich, Visarut; Chavadej, Sumaeth; o’Haver, John H.; Rujiravanit, Ratana (2010). "Removal of trace Cd2+ using continuous multistage ion foam fractionation: Part I—The effect of feed SDS/Cd molar ratio". Journal of Hazardous Materials. 182 (1–3): 812–9. doi:10.1016/j.jhazmat.2010.06.111. PMID 20667426.

- Banerjee, Rintu; Agnihotri, Rajeev; Bhattacharyya, B. C. (1993). "Purification of alkaline protease of Rhizopus oryzae by foam fractionation". Bioprocess Engineering. 9 (6): 245. doi:10.1007/BF01061529.

- Brown, A. K.; Kaul, A.; Varley, J. (1999). "Continuous foaming for protein recovery: Part I. Recovery of ?-casein". Biotechnology and Bioengineering. 62 (3): 278–90. doi:10.1002/(SICI)1097-0290(19990205)62:3<278::AID-BIT4>3.0.CO;2-D. PMID 10099539.

- Santana, C.C., Liping Due, Robert D. Tanner. "Downstreaming Processing of Proteins using Foam Fractionation." Biotechnology Vol. IV. http://www.eolss.net/Sample-Chapters/C17/E6-58-04-03.pdf

- Parthasarathy, S.; Das, T. R.; Kumar, R.; Gopalakrishnan, K. S. (1988). "Foam separation of microbial cells" (PDF). Biotechnology and Bioengineering. 32 (2): 174–83. doi:10.1002/bit.260320207. PMID 18584733.

- Burghoff, B (2012). "Foam fractionation applications". Journal of Biotechnology. 161 (2): 126–37. doi:10.1016/j.jbiotec.2012.03.008. PMID 22484126.

- Shea, A. P.; Crofcheck, C. L.; Payne, F. A.; Xiong, Y. L. (2009). "Foam fractionation of α-lactalbumin and β-lactoglobulin from a whey solution". Asia-Pacific Journal of Chemical Engineering. 4 (2): 191. doi:10.1002/apj.221.

- Ekici, P; Backleh-Sohrt, M; Parlar, H (2005). "High efficiency enrichment of total and single whey proteins by pH controlled foam fractionation". International Journal of Food Sciences and Nutrition. 56 (3): 223–9. doi:10.1080/09637480500146549. PMID 16009637.

- Turhan, K.N., and M.R. Etzel. "Whey Protein Isolate and -Lactalbumin Recovery from Lactic Acid Whey Using Cation-Exchange Chromatography." Journal of Food Science 69.2 (2004): 66-70. Print.

- Muller, Arabelle, George Daufin, and Bernard Chaufer. "Ultrafiltration Modes of Operation for the Separation of A-lactalbumin from Acid Casein Whey." Journal of Membrane Science 153 (199): 9-21. Print.