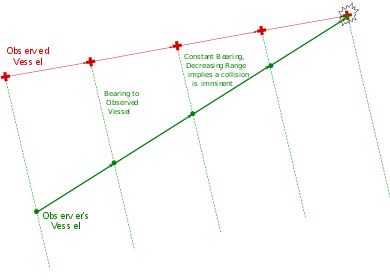

Constant bearing, decreasing range

Constant bearing, decreasing range (CBDR) is a term in navigation which means that some object, usually another ship viewed from the deck or bridge of one's own ship, is getting closer but maintaining the same relative bearing. If this continues, the objects will collide.[1][2][3]

Risk

Sailors, especially deck hands and those who stand watch on the bridge, are trained to watch for this situation and make it known when they detect it happening. The reasoning is subtle: non-sailors who are used to driving automobiles normally are able to detect the possible risk of a collision with implicit reference to the background (e.g., the street, the scenery, the landscape, etc.) At sea, when vessels are borne in water, the sea surface removes this vital visual clue. Unaware individuals tend to gauge the risk of two vessels colliding based on which direction each vessel is heading. In other words, a novice will think that two vessels which appear to be heading apart from each other cannot collide. This is false, as when a faster vessel is overtaking a slower one, they can in fact have a collision even though the vessels are on substantially different headings.

On a river, CBDR is less useful, as it is likely that both the observed and the observing vessel will follow curving courses along the waterway, whether or not they are on a collision course. In such situations safe navigation depends on upstream and downstream traffic keeping to separate sectors of the navigable channel.[4]

Visual clues

When a non-moving background (typically the shore line) is present, CBDR situations can be recognized by the fact that some part of the moving target vessel is not visually moving against the background. On the other hand, if the target vessel visually moves forward against the background, with relative bearing decreasing, then the target vessel will pass in front of the observing vessel and there is no risk of collision, provided both vessels maintain constant speed and course. Similarly, if the target vessel visually moves backwards against the background, with relative bearing increasing, the target vessel will pass behind the observing vessel. However, this method of recognizing non-CBDR conditions is only true for relatively small observing vessels. With larger vessels, only an observer positioned near the bow can reliably make the first conclusion, whereas the second conclusion can only be left to an observer positioned near the stern.

Relative bearing

Another source of confusion arises from the distinction between relative bearing and absolute bearing. One might think that another vessel which seems to be progressing from, perhaps, dead ahead to apparent movement down one's starboard side cannot result in a collision. This is not quite true. Because a vessel afloat can change its true heading (relative to north) without obvious detection (unless there are landmarks in sight) two vessels may collide even if one presents a substantially changing relative bearing.

Road safety

The phenomenon also presents itself in road safety. At the crossing of two straight roads, a CBDR condition may occur and keep one vehicle in the other's blind spot.[5] Even without blind spots, the lack of optic flow makes for harder spotting.[6]

See also

References

- Peppe, Kevin (Commander, US Navy) (December 1996). "Constant Bearing, Decreasing Range". US Naval Institute Proceedings. 122 (12/1): 126.

- Logan, Doug. "Collision Course with a Crossing Boat? How to Know". Boats.com. Retrieved 18 August 2017.

- "Collision Course with a Crossing Boat? How to Know" (PDF). Gulf Coast Sailing School. Retrieved 18 August 2017.

- Smith, Gregory L. (Captain) (February 2017). "For river pilots, tri-sectoring most effective way to determine collision risk". Professional Mariner (February 2017).

- Bez (2018). "Collision Course [Ipley Cross]: Why This Type Of Road Junction Will Keep Killing Cyclists". Singletrack.

- Green, Marc (2013). "A Crash Course In Collisions: The CBDR Rule". www.visualexpert.com.