Constance Peel

Constance Dorothy Evelyn Peel OBE (née Bayliff; 27 April 1868 – 7 August 1934) was an English journalist and writer, known for her non-fiction books on cheap household management and cookery. She wrote with the name Mrs. C. S. Peel, taking the name of her husband, Charles Steers Peel. She is sometimes cited as Dorothy Constance Peel.[1] After the First World War, she worked on behalf of women, sitting on governmental committees.

Constance Dorothy Evelyn Peel OBE | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | Constance Dorothy Evelyn Bayliff 27 April 1868 Ganarew, Herefordshire, England |

| Died | 7 August 1934 (aged 66) Kensington, London, England |

| Pen name | Mrs. C. S. Peel; Dorothy Constance Peel |

| Occupation | Writer and journalist |

| Language | English |

| Education | Home-schooled |

| Subject | House-keeping, cookery, life of women |

| Notable awards | OBE (1919) |

| Spouse | Charles Steers Peel |

| Relatives | Robert Peel (grandfather) |

Early life

Constance Bayliff was born in Ganarew, Herefordshire on 27 April 1868. She was the seventh child of Richard Lane Bayliff, a military captain, and his wife Henrietta née Peel. As a young child, Constance Bayliff lived in Wyesham, Monmouthshire, before she moved to Bristol. She was primarily educated at home and suffered from breathing problems. At seventeen, she moved to Folkestone and had a coming out at a military ball. In her childhood, she spent much time socialising with families much richer than her own; she had actually had a fairly frugal upbringing.[2]

Career and marriage

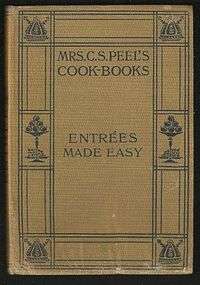

Bayliff began a career in journalism when she and her family moved to Twickenham. An older sister was producing illustrations for a periodical called The Queen, and Peel won a competition to write for Woman. Arnold Bennett, then editor of the periodical, arranged for Peel to receive tutorship from a schoolteacher, and she also learnt from Bennett's editing. In December 1894, Bayliff married electrical engineer Charles Steers Peel, her second cousin, and the couple moved to Dewsbury. After this point, she wrote under the name Mrs. C. S. Peel. The couple had two daughters but lost a third child. Peel's first book, 1898's The New Home, drew upon her experience of starting her household on modest means. Between 1903 and 1906, Peel edited the periodicals Hearth and Home, Woman and Myra's Journal, and authored a series of cookery books.[2]

Peel changed career after losing a child, opening a hat shop with Ethel Kentish, her friend. The shop was successful, and clientele included actress Ellen Terry. However, the business closed down due to Peel's ill health, and in 1913, she returned to writing.[2] Peel became editor of The Queen and wrote for Hearth and Home and The Lady. In 1914, she published the first of her four novels, this one called The Hat Shop. Works of non-fiction written in the 1910s included Marriage on Small Means, published in 1914, and The Labour Saving House, published in 1917. During the First World War, Peel ran a Lambeth-based club for the wives of servicemen, and spoke on behalf of the United Workers' Association and the National War Savings Association. She co-directed, with Maud Pember Reeves, the women's service of the Ministry of Food during the voluntary rationing of 1917-8, as well as publicly speaking about economical household food practices.[2]

She was editor of the women's page of The Daily Mail after being appointed to the post in 1918 by Lord Northcliffe, though she left the position after being diagnosed with diabetes in 1920. She was awarded an OBE in 1919. After the war, Peel worked towards the improvement of women's domestic lives, sitting on committees addressing domestic service and working-class housing for the Ministry of Reconstruction, as well as committees organised by other organisations. She also became vice-president of the British Women Housewives' Association.[2]

Later life and legacy

Peel produced memoirs spanning five volumes. Her autobiography, Life's Enchanted Cup: an Autobiography, 1872–1933 was published in 1933. She died in Kensington, London, on 7 August 1934, due to her myocarditis and diabetes, and was survived by her husband.[2]

An article in The Times commented on Peel's highly varied career, saying that "her industry was astonishing, for she went down coalmines, inspected prisons, reformatories and factories, examined schools and studied diet for the young, in addition to regular journalism and four novels".[3] The social historian John Burnett called her "the doyenne of writers on domestic economy".[4]

References

- See, for example, Darling, Elizabeth (2007). "'The house that is a woman's book come true': The all-Europe house and four women's spatial practices in inter-war England". In Elizabeth Darling; Lesley Whitworth (eds.). Women and the Making of Built Space in England, 1870–1950. Ashgate. pp. 123–42. ISBN 9780754651857.

- Ryan, Deborah S. (2004). "Peel [née Bayliff], Constance Dorothy Evelyn (1868–1934)" ((subscription or UK public library membership required)). Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/56783. Retrieved 29 January 2014.

- Cardinal, Agnes; Goldman, Dorothy; Hattaway, Judith (1999). Women's Writing on the First World War. Oxford University Press. p. 147. ISBN 9780198122807.CS1 maint: uses authors parameter (link)

- Burnett, John (2013). Plenty and Want. Routledge. p. 265. ISBN 9781136090844.

External links

- Works by Constance Peel at Project Gutenberg

- A Year in Public Life, Mrs. C. S. Peel, 1919. Hosted by Archive.org