Congo Canyon

Congo Canyon is a submarine canyon found at the end of the Congo River in Africa. It is one of the largest submarine canyons in the world.[1]

Size

The canyon begins inland on the continent, partway up the Congo Estuary, and starts at a depth of 21 meters. It cuts across the entire continental shelf for 85 kilometers until it reaches the shelf edge, then continues down the slope and ends 280 km from where it started. At its deepest point, the V-shaped canyon walls are 1100 meters tall, and the maximum width of the canyon is about 9 miles.[2] At the bottom of the continental slope, it enters the Congo deep-sea fan and extends for an additional 220 km.

Turbidity currents

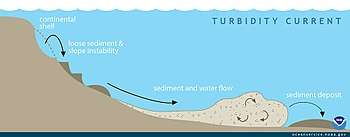

The turbidity currents found in Congo Canyon are the strongest measured in the world.[3] These are essentially underwater avalanches that can propagate for hundreds of kilometers, and their strength and frequency correlate strongly with the period of highest outflow from the Congo River. Their speeds vary from about 0.7 m/s to 3.5 m/s and events can last for more than a week.[4] These currents are the major source of erosion in the canyon and represent a significant portion of the sediment that ends up in the fan at the end of the canyon. They commonly destroy equipment laid on the bottom of the ocean and have destroyed telegraph cables and moorings.[1]

Congo Deep-Sea Fan

Unlike other rivers that empty into the sea, the Congo River is not building a delta because essentially all of its sediments are carried by turbidity currents via the submarine canyon to the fan. This accumulation is probably the greatest in the world for a currently active submarine system.[5] The fan is built up by sediment gravity flows and other submarine mass movements, but also represents a very large active turbidite system. Although there exists a net up-canyon bottom current due to upwelling,[6] these events overwhelm the normal bottom flow and ensure continued deposition.

References

- Heezen, B.C.; et al. (July 1964). "Congo Submarine Canyon". Bulletin of the American Association of Petroleum Geologists. 48 (7): 1128–1149. Retrieved 17 March 2016.

- "Congo Canyon". Encyclopædia Britannica Academic. Encyclopædia Britannica Inc. Retrieved 17 March 2016.

- Cooper, Cortis; Wood, Jon; Andrieux, Olivier. "Turbidity Current Measurements in the Congo Canyon". www.onepetro.org. Offshore Technology Conference. Retrieved 7 April 2016.

- Vangriesheim, Annick; Khripounoff, Alexis; Crassous, Philippe (November 2009). "Turbidity events observed in situ along the Congo submarine channel" (PDF). Deep-Sea Research Part II: Topical Studies in Oceanography. 56 (23): 2208–2222. doi:10.1016/j.dsr2.2009.04.004. Retrieved 7 April 2016.

- Savoye, Bruno; Babonneau, Nathalie; Dennielou, Bernard; Bez, Martine (November 2009). "Geological overview of the Angola–Congo margin, the Congo deep-sea fan and its submarine valleys" (PDF). Deep-Sea Research Part II: Topical Studies in Oceanography. 56 (23): 2169–2182. doi:10.1016/j.dsr2.2009.04.001.

- Marshall Crossland, J.I.; Crossland, C.J.; Swaney, D.P. "Congo (Zaire) River Estuary, Democratic Republic of the Congo". Baltic Nest Institute. Retrieved 17 March 2016.