Computer Bismarck

Computer Bismarck is a computer wargame developed and published by Strategic Simulations, Inc. (SSI) in 1980. The game is based on the last battle of the battleship Bismarck, in which British Armed Forces pursue the German Bismarck in 1941. It is SSI's first game, and features turn-based gameplay and two-dimensional graphics.

| Computer Bismarck | |

|---|---|

Front cover art of Computer Bismarck. Artwork designed by Louis Saekow. | |

| Developer(s) | Strategic Simulations Inc. |

| Publisher(s) | Strategic Simulations Inc. |

| Designer(s) | Joel Billings, John Lyons |

| Platform(s) | Apple II, TRS-80[1][2] |

| Release | February 1980[3] |

| Genre(s) | Wargame |

| Mode(s) | Single-player, multiplayer |

The development staff consisted of two programmers, Joel Billings and John Lyons, who programmed the game in BASIC. Originally developed for the TRS-80, an Apple II version was also created two months into the process. After meeting with other wargame developers, Billings decided to publish the game as well. To help accomplish this, he hired Louis Saekow to create the box art.

The first commercially published computer war game, Computer Bismarck sold well and contributed to SSI's success. It is also credited in part for legitimizing war games and computer games.

Synopsis

The game is a simulation of the German battleship Bismarck's last battle in the Atlantic Ocean during World War II.[4] On May 24, 1941, Bismarck and Prinz Eugen sank the British HMS Hood and damaged HMS Prince of Wales at the Battle of the Denmark Strait. Following the battle, British Royal Navy ships and aircraft pursued Bismarck for two days. After being crippled by a torpedo bomber on the evening of May 26, Bismarck was sunk the following morning.[5]

Gameplay

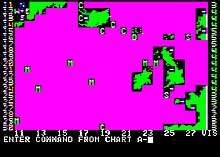

Computer Bismarck is a turn-based computer wargame in which players control British forces against the battleship Bismarck and other German units. The German forces can be controlled by either a computer opponent (named "Otto von Computer") or a second player.[4][6] The game takes place on a map of the North Atlantic Ocean on which letters from the English alphabet represent military units and facilities (airfields and ports).[7] Units have different capabilities, as well as statistics that determine their mobility, firepower, vulnerability and other gameplay factors. Turns take the form of phases, and players alternate inputting orders to maneuver their respective units.[8] Phases can serve different functions, such as informing players of status changes, unit movement, and battles.[7] Players earn points by destroying their opponent's units. After the Bismarck is sunk or a number of turns have occurred, the game ends.[8] Depending on the number of points players have earned, either the British or German forces are declared the victor.[8]

Development

During college, Joel Billings used computers to do econometrics, mathematical modeling and forecasting. This experience led him to believe that computers could handle war games and remove tedious paperwork from gameplay.[9] While between his undergraduate and graduate education, Billings met an IBM programmer and discussed computers.[3][9] Billings suggested starting a software company with him, but the programmer was not interested in war games, stating that they were too difficult and complicated to be popular.[9] Billings posted flyers at hobby shops in the Santa Clara, California area to attract war-game enthusiasts with a background in programming. John Lyons was the first to reply and joined Billings after quickly developing a good rapport.[3][1][9]

Billings chose the Bismarck's last battle because he felt it would be easier to develop than other war games.[1] Computer Bismarck was written in BASIC and compiled to increase its processing speed.[1][9] In August 1979, Billings provided Lyons with access to a computer to write the program. Lyons began programming a simplified version similar to a fox and hounds game—he had "hounds" search a playing field for a "fox". At the time, the two were working full-time and programmed at Billings' apartment during the night. Lyons did the bulk of the programming, while Billings focused on design and assisted with data entry and minor programming tasks.[1]

The game was originally developed for the Tandy Corporation's TRS-80. Two months into development, Billings met with Trip Hawkins, then a marketing manager at Apple Computers, via a venture capitalist, who convinced Billings to develop the game for the Apple II;[1][9] he commented that the computer's capacity for color graphics made it the best platform for strategy games.[3] In October 1979, Billings' uncle gave him an Apple II. Billings and Lyons then converted their existing code to work on the Apple II and used a graphics software package to generate the game's map.[1]

After Lyons began programming, Billings started to study the video games market. He visited local game stores and attended a San Francisco gaming convention. Billings approached Tom Shaw from Avalon Hill—the company produced many war games that Billings played as a child—and one of the founders of Automated Simulations to share market data, but aroused no interest. The lukewarm responses made Billings believe he would have to publish SSI's games. After Computer Bismarck was finished in January 1980, he searched for a graphic designer to handle the game's packaging.[1]

Billings met Louis Saekow through a string of friends but was hesitant to hire him. Inspired by Avalon Hill's games, Billings wanted SSI's games to look professional and include maps, detailed manuals, and excellent box art. Two months prior, Saekow had postponed medical school to pursue his dream of becoming a graphic designer. To secure the job, Saekow told Billings that he could withhold pay if the work was unsatisfactory. In creating the box art, Saekow used a stat camera; his roommate worked for a magazine company and helped him sneak in to use its camera after hours. Saekow's cousin then handled printing the packaging.[1] Without any storage for the complete products, Billings stored the first 2,000 boxes in his bedroom.[3][1] In February 1980, he distributed 30,000 flyers to Apple II owners, and displayed the game at the Applefest exposition a month later.[3] SSI purchased a full-page advertisement for the Apple II version in the March 1980 issue of BYTE magazine, which mentioned the ability to save a game in progress as well as play against the computer or another person. The advertisement also promised future support for the TRS-80 and other computers.[6]

Reception and legacy

In 1980, Peter Ansoff of BYTE magazine called Computer Bismarck a "milestone in the development of commercial war games", and approved of the quality of the documentation and the option to play against the computer, but disapproved of the game. Acknowledging that "it is perhaps unfair to expect the first published [computer war game] to be a fully developed product", he criticized Computer Bismarck for overly faithfully copying the mechanics of the Bismarck board game, including those that worked efficiently on a board but less so on a computer. Ansoff also noted that the computer game "perpetuates the [board game's] irritating system of ship-movement rates", and concluded that "the failings of Computer Bismarck can be summarized by saying that it does not take advantage of the possibilities offered by the computer".[8]

The game was better received by other critics. Neil Shapiro of Popular Mechanics that year praised the game's detail and ability to recreate the complex maneuvering involved in the real battle. He referred to it as unique and "fantastic".[10] In Creative Computing, Randy Heuer cautioned that the game "is probably not for everyone. The point which I probably cannot emphasize enough is that it is an extremely complex simulation ... However, for those ready for a [challenge] ... I enthusiastically recommend Computer Bismarck".[7] Reviewing Computer Bismarck in The Space Gamer magazine, Joseph T. Suchar called the game "superb" and stated that "it has so many strategic options for both sides that it is unlikely to be optimized."[11]

United States Navy defense researcher Peter Perla in 1990 considered war games like Computer Bismarck a step above earlier war-themed video games that relied on arcade-style action. He praised the addition of a computer-controlled opponent that such games provide to solitaire players. Perla attributes SSI's success to the release of its early wargames, specifically citing Computer Bismarck.[12] Computer Gaming World's Bob Proctor in 1988 agreed that Computer Bismarck contributed to SSI's success, commenting that the title earned the company a good profit. He also stated that it encouraged game enthusiasts to submit their own games to SSI, which he believed helped further the company's success. Describing it as the first "serious wargame for a microcomputer", Proctor credited Computer Bismarck with helping to legitimize war games and computer games in general. He stated that the professional packaging demonstrated SSI's seriousness to produce quality products;[3] prior to Computer Bismarck, most computer games were packaged in zipper storage bags.[3][1] Saekow became a permanent SSI employee and designed artwork for most of its products.[1]

Ansoff noted the similarity of the game's mechanics to Avalon Hill's Bismarck, stating that "it would seem proper as a matter of courtesy to acknowledge that the game was based on an Avalon Hill design".[8] In 1983, Avalon Hill took legal action against SSI for copying game mechanics from its board games; Computer Bismarck, among other titles, was involved in the case. The two companies settled the issue out of court.[4] The game was later re-released as part of the company's "SSI classics" line of popular games at discounted prices.[13] One of SSI's later games, Pursuit of the Graf Spee, uses an altered version of Computer Bismarck's core system.[9][14][15] In December 2013 the International Center for the History of Electronic Games received a software donation of several SSI games, including Computer Bismarck with the source code for preservation.[16][17]

References

- Ritchie, Craig (October 2007). "Developer Lookback: Strategic Simulations Inc". Retro Gamer. No. 42. Imagine Publishing. pp. 34–39.

- R.R. Bowker Company; Bantam Books (1983). Bowker/Bantam 1984 Complete Sourcebook of Personal Computing. Bowker. p. 251. ISBN 0-8352-1765-5.

- Proctor, Bob (March 1988). "Titans of the Computer Gaming World". Computer Gaming World (45): 36.

- DeMaria, Rusel; Wilson, Johnny L. (2003). High Score!: The Illustrated History of Electronic Games (2 ed.). McGraw-Hill Osborne Media. pp. 158–159. ISBN 0-07-223172-6.

- Kennedy, Ludovic (1974). Pursuit: The Sinking of the Bismarck. William Collins Sons & Co Ltd. ISBN 0-00-211739-8.

- "Sink the Bismarck with your Apple! (advertisement)". BYTE. March 1980. p. 165. Retrieved 18 October 2013.

- Heuer, Randy (August 1980). "Computer Bismarck". Creative Computing. p. 31. Retrieved 18 October 2013.

- Ansoff, Peter A (December 1980). "Computer Bismarck". BYTE. pp. 262–266. Retrieved 18 October 2013.

- Powell, Jack (July 1985). "War Games: The story of S.S.I." Antic. Vol. 4 no. 3. p. 28.

- Shapiro, Neil (August 1980). "PM Electronics Monitor: Have your own war room". Popular Mechanics. Vol. 154 no. 2. p. 13.

- Suchar, Joseph T. (July 1980). "Capsule Reviews". The Space Gamer. Steve Jackson Games (29): 29–30.

- Perla, Peter P. (1990). The Art of Wargaming. Naval Institute Press. pp. 151–152. ISBN 0-87021-050-5.

- Antic Staff (February 1987). "New Products". Antic. Vol. 5 no. 10. p. 31.

- Murphy, Brian J. (July 1983). "Warfare in the Atlantic". Creative Computing. Vol. 9 no. 7. Ziff Davis. p. 76.

- Computer Gaming World Staff (January–February 1982). "Hobby and Industry News". Computer Gaming World. 2 (1): 2.

- Nutt, Christian (2013-12-16). "Strategic Simulations, Inc. founder donates company collection to ICHEG". Gamasutra. Retrieved 22 December 2013.

- Dyson, Jon-Paul C. (2013-12-16). "The Strategic Simulations, Inc. Collection". ICHEG. Archived from the original on 24 December 2013. Retrieved 22 December 2013.