Computational neurogenetic modeling

Computational neurogenetic modeling (CNGM) is concerned with the study and development of dynamic neuronal models for modeling brain functions with respect to genes and dynamic interactions between genes. These include neural network models and their integration with gene network models. This area brings together knowledge from various scientific disciplines, such as computer and information science, neuroscience and cognitive science, genetics and molecular biology, as well as engineering.

Levels of processing

Molecular kinetics

Models of the kinetics of proteins and ion channels associated with neuron activity represent the lowest level of modeling in a computational neurogenetic model. The altered activity of proteins in some diseases, such as the amyloid beta protein in Alzheimer's disease, must be modeled at the molecular level to accurately predict the effect on cognition.[1] Ion channels, which are vital to the propagation of action potentials, are another molecule that may be modeled to more accurately reflect biological processes. For instance, to accurately model synaptic plasticity (the strengthening or weakening of synapses) and memory, it is necessary to model the activity of the NMDA receptor (NMDAR). The speed at which the NMDA receptor lets Calcium ions into the cell in response to Glutamate is an important determinant of Long-term potentiation via the insertion of AMPA receptors (AMPAR) into the plasma membrane at the synapse of the postsynaptic cell (the cell that receives the neurotransmitters from the presynaptic cell).[2]

Genetic regulatory network

In most models of neural systems neurons are the most basic unit modeled.[2] In computational neurogenetic modeling, to better simulate processes that are responsible for synaptic activity and connectivity, the genes responsible are modeled for each neuron.

A gene regulatory network, protein regulatory network, or gene/protein regulatory network, is the level of processing in a computational neurogenetic model that models the interactions of genes and proteins relevant to synaptic activity and general cell functions. Genes and proteins are modeled as individual nodes, and the interactions that influence a gene are modeled as excitatory (increases gene/protein expression) or inhibitory (decreases gene/protein expression) inputs that are weighted to reflect the effect a gene or protein is having on another gene or protein. Gene regulatory networks are typically designed using data from microarrays.[2]

Modeling of genes and proteins allows individual responses of neurons in an artificial neural network that mimic responses in biological nervous systems, such as division (adding new neurons to the artificial neural network), creation of proteins to expand their cell membrane and foster neurite outgrowth (and thus stronger connections with other neurons), up-regulate or down-regulate receptors at synapses (increasing or decreasing the weight (strength) of synaptic inputs), uptake more neurotransmitters, change into different types of neurons, or die due to necrosis or apoptosis. The creation and analysis of these networks can be divided into two sub-areas of research: the gene up-regulation that is involved in the normal functions of a neuron, such as growth, metabolism, and synapsing; and the effects of mutated genes on neurons and cognitive functions.[3]

Artificial neural network

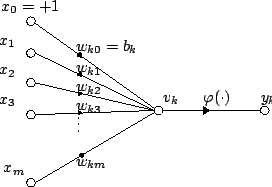

An artificial neural network generally refers to any computational model that mimics the central nervous system, with capabilities such as learning and pattern recognition. With regards to computational neurogenetic modeling, however, it is often used to refer to those specifically designed for biological accuracy rather than computational efficiency. Individual neurons are the basic unit of an artificial neural network, with each neuron acting as a node. Each node receives weighted signals from other nodes that are either excitatory or inhibitory. To determine the output, a transfer function (or activation function) evaluates the sum of the weighted signals and, in some artificial neural networks, their input rate. Signal weights are strengthened (long-term potentiation) or weakened (long-term depression) depending on how synchronous the presynaptic and postsynaptic activation rates are (Hebbian theory).[2]

The synaptic activity of individual neurons is modeled using equations to determine the temporal (and in some cases, spatial) summation of synaptic signals, membrane potential, threshold for action potential generation, the absolute and relative refractory period, and optionally ion receptor channel kinetics and Gaussian noise (to increase biological accuracy by incorporation of random elements). In addition to connectivity, some types of artificial neural networks, such as spiking neural networks, also model the distance between neurons, and its effect on the synaptic weight (the strength of a synaptic transmission).[4]

Combining gene regulatory networks and artificial neural networks

For the parameters in the gene regulatory network to affect the neurons in the artificial neural network as intended there must be some connection between them. In an organizational context, each node (neuron) in the artificial neural network has its own gene regulatory network associated with it. The weights (and in some networks, frequencies of synaptic transmission to the node), and the resulting membrane potential of the node (including whether an action potential is produced or not), affect the expression of different genes in the gene regulatory network. Factors affecting connections between neurons, such as synaptic plasticity, can be modeled by inputting the values of synaptic activity-associated genes and proteins to a function that re-evaluates the weight of an input from a particular neuron in the artificial neural network.

Incorporation of other cell types

Other cell types besides neurons can be modeled as well. Glial cells, such as astroglia and microglia, as well as endothelial cells, could be included in an artificial neural network. This would enable modeling of diseases where pathological effects may occur from sources other than neurons, such as Alzheimer's disease.[1]

Factors affecting choice of artificial neural network

While the term artificial neural network is usually used in computational neurogenetic modeling to refer to models of the central nervous system meant to possess biological accuracy, the general use of the term can be applied to many gene regulatory networks as well.

Time variance

Artificial neural networks, depending on type, may or may not take into account the timing of inputs. Those that do, such as spiking neural networks, fire only when the pooled inputs reach a membrane potential is reached. Because this mimics the firing of biological neurons, spiking neural networks are viewed as a more biologically accurate model of synaptic activity.[2]

Growth and shrinkage

To accurately model the central nervous system, creation and death of neurons should be modeled as well.[2] To accomplish this, constructive artificial neural networks that are able to grow or shrink to adapt to inputs are often used. Evolving connectionist systems are a subtype of constructive artificial neural networks (evolving in this case referring to changing the structure of its neural network rather than by mutation and natural selection).[5]

Randomness

Both synaptic transmission and gene-protein interactions are stochastic in nature. To model biological nervous systems with greater fidelity some form of randomness is often introduced into the network. Artificial neural networks modified in this manner are often labeled as probabilistic versions of their neural network sub-type (e.g., pSNN).[6]

Incorporation of fuzzy logic

Fuzzy logic is a system of reasoning that enables an artificial neural network to deal in non-binary and linguistic variables. Biological data is often unable to be processed using Boolean logic, and moreover accurate modeling of the capabilities of biological nervous systems requires fuzzy logic. Therefore, artificial neural networks that incorporate it, such as evolving fuzzy neural networks (EFuNN) or Dynamic Evolving Neural-Fuzzy Inference Systems (DENFIS), are often used in computational neurogenetic modeling. The use of fuzzy logic is especially relevant in gene regulatory networks, as the modeling of protein binding strength often requires non-binary variables.[2][5]

Types of learning

Artificial Neural Networks designed to simulate of the human brain require an ability to learn a variety of tasks that is not required by those designed to accomplish a specific task. Supervised learning is a mechanism by which an artificial neural network can learn by receiving a number of inputs with a correct output already known. An example of an artificial neural network that uses supervised learning is a multilayer perceptron (MLP). In unsupervised learning, an artificial neural network is trained using only inputs. Unsupervised learning is the learning mechanism by which a type of artificial neural network known as a self-organizing map (SOM) learns. Some types of artificial neural network, such as evolving connectionist systems, can learn in both a supervised and unsupervised manner.[2]

Improvement

Both gene regulatory networks and artificial neural networks have two main strategies for improving their accuracy. In both cases the output of the network is measured against known biological data using some function, and subsequent improvements are made by altering the structure of the network. A common test of accuracy for artificial neural networks is to compare some parameter of the model to data acquired from biological neural systems, such as from an EEG.[7] In the case of EEG recordings, the local field potential (LFP) of the artificial neural network is taken and compared to EEG data acquired from human patients. The relative intensity ratio (RIRs) and fast Fourier transform (FFT) of the EEG are compared with those generated by the artificial neural networks to determine the accuracy of the model.[8]

Genetic algorithm

Because the amount of data on the interplay of genes and neurons and their effects is not enough to construct a rigorous model, evolutionary computation is used to optimize artificial neural networks and gene regulatory networks, a common technique being the genetic algorithm. A genetic algorithm is a process that can be used to refine models by mimicking the process of natural selection observed in biological ecosystems. The primary advantages are that, due to not requiring derivative information, it can be applied to black box problems and multimodal optimization. The typical process for using genetic algorithms to refine a gene regulatory network is: first, create a population; next, to create offspring via a crossover operation and evaluate their fitness; then, on a group chosen for high fitness, simulate mutation via a mutation operator; finally, taking the now mutated group, repeat this process until a desired level of fitness is demonstrated. [9]

Evolving systems

Methods by which artificial neural networks may alter their structure without simulated mutation and fitness selection have been developed. A dynamically evolving neural network is one approach, as the creation of new connections and new neurons can be modeled as the system adapts to new data. This enables the network to evolve in modeling accuracy without simulated natural selection. One method by which dynamically evolving networks may be optimized, called evolving layer neuron aggregation, combines neurons with sufficiently similar input weights into one neuron. This can take place during the training of the network, referred to as online aggregation, or between periods of training, referred to as offline aggregation. Experiments have suggested that offline aggregation is more efficient.[5]

Potential applications

A variety of potential applications have been suggested for accurate computational neurogenetic models, such as simulating genetic diseases, examining the impact of potential treatments,[10] better understanding of learning and cognition,[11] and development of hardware able to interface with neurons.[4]

The simulation of disease states is of particular interest, as modeling both the neurons and their genes and proteins allows linking genetic mutations and protein abnormalities to pathological effects in the central nervous system. Among those diseases suggested as being possible targets of computational neurogenetic modeling based analysis are epilepsy, schizophrenia, mental retardation, brain aging and Alzheimer's disease, and Parkinson's disease.[2]

See also

References

- Kasabov, Nikola K.; Schliebs, Reinhard; Kojima, Hiroshi (2011). "Probabilistic Computational Neurogenetic Modeling: From Cognitive Systems to Alzheimer's Disease". IEEE Transactions on Autonomous Mental Development. 3 (4): 300–311. doi:10.1109/tamd.2011.2159839.

- Benuskova, Lubica; Kasabov, Nikola (2007). Computational Neurogenetic Modeling. New York: Springer. ISBN 978-0-387-48353-5.

- Benuskova, L.; Kasabov, N. (2008). "Modeling brain dynamics using computational neurogenetic approach". Cognitive Neurodynamics. 2 (4): 319–334. doi:10.1007/s11571-008-9061-1. PMC 2585617. PMID 19003458.

- Kasabov, Nikola; Benuskova, Lubica (2004). "Computational Neurogenetics". Journal of Computational and Theoretical Nanoscience. 1: 47–61. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.149.6631. doi:10.1166/jctn.2004.006.

- Watts, Michael J (2009). "A Decade of Kasabov's Evolving Connectionist Systems: A Review". IEEE Transactions on Systems, Man, and Cybernetics - Part C: Applications and Reviews. 39 (3): 253–269. doi:10.1109/TSMCC.2008.2012254.

- Kasabov, N.; Schliebs, S.; Mohemmed, A. (2012). Modelling the Effect of Genes on the Dynamics of Probabilistic Spiking Neural Networks for Computational Neurogenetic Modelling. Computational Intelligence Methods for Bioinformatics and Biostatistics. Lecture Notes in Computer Science. 7548. pp. 1–9. doi:10.1007/978-3-642-35686-5_1. hdl:10292/1663. ISBN 978-3-642-35685-8.

- Benuskova, L.; Wysoski, S. G.; Kasabov, N. Computational Neurogenetic Modeling: A Methodology to Study Gene Interactions Underlying Neural Oscillations. 2006 International Joint Conference on Neural Networks. Vancouver, BC. pp. 4638–4644. doi:10.1109/IJCNN.2006.1716743. hdl:10292/596.

- Kasabov, N.; Benuskova, L.; Wysoski, S. G. (2005). Computational neurogenetic modeling: Integration of spiking neural networks, gene networks, and signal processing techniques. Artificial Neural Networks: Formal Models and Their Applications - Icann 2005, Pt 2, Proceedings. 3697. pp. 509–514. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.106.5223.

- Kasabov, N (2006). Neuro-, genetic-, and quantum inspired evolving intelligent systems. International Symposium on Evolving Fuzzy Systems, Proceedings. pp. 63–73. doi:10.1109/ISEFS.2006.251165. hdl:10292/603. ISBN 978-0-7803-9718-7.

- Kasabov, N.; Benuskova, L.; Wysoski, S. G. (2005). "Biologically plausible computational neurogenetic models: Modeling the interaction between genes, neurons and neural networks". Journal of Computational and Theoretical Nanoscience. 2 (4): 569–573. Bibcode:2005JCTN....2..569K. doi:10.1166/jctn.2005.012.

- Benuskova, Lubica; Jain, Vishal; Wysoski, Simei G.; Kasabov, Nikola K. (2006). "Computational neurogenetic modelling: A pathway to new discoveries in genetic neuroscience". International Journal of Neural Systems. 16 (3): 47–61. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.149.5411. doi:10.1142/S0129065706000627. PMID 17044242.