Common mudpuppy

The common mudpuppy (Necturus maculosus) is a species of salamander in the genus Necturus.[2] They live an entirely aquatic lifestyle in the eastern part of North America in lakes, rivers, and ponds. They go through paedomorphosis and retain their external gills.[3] Because skin and lung respiration alone is not sufficient for gas exchange, mudpuppies must rely on external gills as their primary means of gas exchange.[4] They are usually a rusty brown color[5] and can grow to an average length of 33 cm (13 in).[6] Mudpuppies are nocturnal creatures, and come out during the day only if the water in which they live is murky.[2] Their diet consists of almost anything they can get in their mouths, including insects, mollusks, and earthworms (as well as other annelids[5]). Once a female mudpuppy reaches sexual maturity at six years of age, she can lay an average of 60 eggs.[5] In the wild, the average lifespan of a mudpuppy is 11 years.[7]

| Common mudpuppy | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Amphibia |

| Order: | Urodela |

| Family: | Proteidae |

| Genus: | Necturus |

| Species: | N. maculosus |

| Binomial name | |

| Necturus maculosus (Rafinesque, 1818) | |

| Synonyms | |

|

Sirena maculosa Rafinesque, 1818 | |

Appearance

Mudpuppies are small and can be compared to the size of a lizard. Mudpuppies can be a rusty brown color with gray and black and usually have blackish-blue spots, but some albino adults have been reported in Arkansas.[5] In clear, light water, their skin gets darker, likewise in darker water, their skin gets lighter in color.[4] At sexual maturity, mudpuppies can be 20 cm (8 in) long and continue to grow to an average length of 33 cm (13 in), though specimens up to 43.5 cm (17.1 in) have been reported.[6] Their external gills resemble ostrich plumes and their size depends on the oxygen levels present in the water. In stagnant water, mudpuppies have larger gills, whereas in running streams where oxygen is more prevalent, they have smaller gills.[3] The distal portions of the gills are very filamentous and contain many capillaries.[6] Mudpuppies also have small, flattened limbs which can be used for slowly walking on the bottoms of streams or ponds, or they can be flattened against the body during short swimming spurts.[6] They have mucous glands which provide a slimy protective coating [3]

Neoteny

Mudpuppies are one of many species of salamanders that fail to undergo metamorphosis. Most hypotheses surrounding the origin of Necturus's lack of metamorphosis concern the effectiveness of the thyroid gland. The thyroid gland in some salamanders, like the axolotl, produce normal thyroid hormones (THs), but cells in the organism express thyroid hormone receptors (TR) that are mutated, and do not bond correctly with thyroid hormones, leading to some salamanders in a state of perpetual juvenile-hood.[8] In contrast to Axolotls, in mudpuppies, these THs are normally expressed. However, it is believed that instead of having TH-insensitive tissues that block the effects of THs, some mudpuppy tissues, such as the external gills, have lost the ability to be regulated by TH over time.[9] This selective insensitivity to THs suggests a normal level of activity in the hypothalamo-pituitary-thyroid axis in developing mudpuppies, unlike other salamander species.

The common mudpuppy also does not have a parathyroid gland.[10] The majority of salamanders with parathyroid glands rely on them to help with hypercalcemic regulation; hypercalcemic regulation in mudpuppies is primarily done by the Pituitary gland instead.[10] In common mudpuppies, the purpose of the absence of a parathyroid gland is poorly understood. One reason for the absence might be the lack of variability in the climate of mudpuppies, as the parathyroid glands of salamanders vary greatly depending on seasonal changes, or whether the organism hibernates.[11]

Distribution

N. maculosus specimens live in streams, lakes, and ponds in the eastern part of North America.[3] They appear in the southern section of Canada, as far south as Georgia, and from the Midwest United States to North Carolina.[7] In the more northern sections, they are called mudpuppies, and in the southern portions, they are called waterdogs.[3] The mudpuppy hides under cover such as rocks and logs during the day and becomes more active at night.[6] However, in muddy waters, the mudpuppy may become active during the day.[2] Mudpuppies can even live under the ice when lakes freeze.[2]

Diet

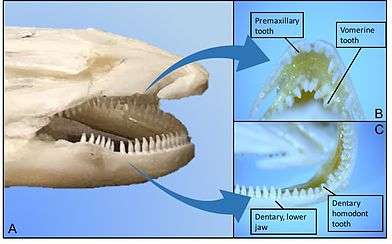

Mudpuppies use rows of teeth to eat their prey.[4] Salamanders have three different sets of teeth: dentary, premaxillary, and vomerine teeth, which are named due to their location in the mouth.[12] All the teeth, despite their different locations, are very similar. They are small and conical, meaning mudpuppies are homodonts due to their similar shape.[13][14] The common mudpuppy never leaves its aquatic environment and therefore does not undergo morphogenesis, however many salamanders do and develop differentiated teeth.[15] Aquatic salamander teeth are used to hinder escape of the prey from the salamander, they do not have a crushing function.[16] This aids the salamander when feeding. When the salamander undergoes the "suck and gape" feeding style, the prey is pulled into the mouth, and the teeth function to hold the prey inside the mouth and prevent the prey from escaping.[12] At both sides of their mouths their lips interlock, which allows them to use suction feeding.[6] They are carnivorous creatures and will eat almost anything they can get into their mouths. Typically they prey upon animals such as insects, mollusks, annelids, small fish, amphibians, earthworms, and spiders. The jaw of a mudpuppy also plays a significant role in its diet. The mudpuppy jaw is considered metaautostyly, like most amphibians, meaning the jaw is more stable and that the salamander has a dentary.[13] This affects their diet by limiting the flexibility of the jaw to take in larger prey. The mudpuppy has few predators but may include fish, crayfish, turtles, and water snakes. Because fishermen frequently catch and discard them, humans are considered to be one of their main predators.[5]

Reproduction

Mudpuppies take six years to reach sexual maturity.[6] Mating typically takes place in autumn, though eggs are not laid till much later.[3] When males are ready to breed, their cloacae become swollen. Males deposit their spermatophores in the substratum of the environment. The female will then pick them up with her cloaca and store them in a small specialized gland, a spermatheca, until the eggs are fertilized.[5] Females store the sperm until ovulation and internal fertilization take place, usually just prior to deposition in the spring.[6] Before the eggs are deposited, male mudpuppies leave the nest.[5] Once ready, the female deposits the eggs in a safe location, usually on the underside of a rock or log.[6] They can lay from 20–200 eggs,[3] usually an average of 60.[5] The eggs are not pigmented and are about 5–6 mm (0.20–0.24 in) mm in diameter. The female stays with her eggs during the incubation period (around 40 days). Hatchlings are about 2.5 cm (0.98 in) long and grow to 3.6 cm (1.4 in) before the yolk is completely consumed.[6]

Subspecies

- N. m. louisianensis Viosca, 1937 (Red River mudpuppy)

- N. m. maculosus (Rafinesque, 1818) (common mudpuppy)

- N. m. stictus Bishop, 1941 (Lake Winnebago mudpuppy)

See also

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Necturus maculosus. |

- Cryptobranchus alleganiensis (hellbender)

- Necturus alabamensis (Alabama waterdog)

- Necturus beyeri (Gulf coast waterdog)

References

- IUCN SSC Amphibian Specialist Group (2015). "Necturus maculosus". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2015: e.T59433A64731610. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2015-4.RLTS.T59433A64731610.en.

- Mattison, Chris (2005). "Mudpuppy." in Encyclopedia of Reptiles and Amphibians: An Essential Guide to Reptiles and Amphibians of the World. Thunder Bay Press, pp. 32–33.

- Halliday, Tim R., and Kraig Adler (eds.) (1986). "Salamanders and Newts." The Encyclopaedia of Reptiles and Amphibians. Oxford: George Allen and Unwin, pp. 18–31.

- Chiasson, Richard B (1969). Laboratory Anatomy of Necturus. 3rd ed. Dubuque: Wm C. Brown.

- Petranka, James W. (1998). Salamanders of the United States and Canada. Washington: Smithsonian Institution.

- Gans, C., and R. A. Nussbaum (1981). "The Mudpuppy." Vertebrates, a Laboratory Text. Ed. Norman K. Wessells and Elizabeth M. Center. 2nd ed. Los Altos, Calif.: W. Kaufmann, pp. 108–41.

- "Mudpuppies, Mudpuppy Pictures, Mudpuppy Facts". Animals, Animal Pictures, Wild Animal Facts – National Geographic. Web. 18 April 2010.

- "Axolotls as models in neoteny and secondary differentiation | Developmental Biology Interactive". www.devbio.biology.gatech.edu. Retrieved 2017-03-19.

- Vlaeminck-Guillem, Virginie; Safi, Rachid; Guillem, Philippe; Leteurtre, Emmanuelle; Duterque-Coquillaud, Martine; Laudet, Vincent (2004-09-01). "Thyroid hormone receptor expression in the obligatory paedomorphic salamander Necturus maculosus". The International Journal of Developmental Biology. 50 (Next). doi:10.1387/ijdb.052094vv. ISSN 0214-6282.

- Duellman, William Edward (1994). Biology of Amphibians. Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins University Press.

- Cortelyou, John R.; McWhinnie, Dolores J. (1967). "Parathyroid Glands of Amphibians. I. Parathyroid Structure and Function in the Amphibian, with Emphasis on Regulation of Mineral Ions in Body Fluids". American Zoologist. 7 (4): 843–855. doi:10.1093/icb/7.4.843. JSTOR 3881518.

- Wessels, Norman K.; Center, Elizabeth M. (1992-01-01). Vertebrates. Jones & Bartlett Learning. ISBN 9780867208535.

- Kardong, Kenneth (2015). Comparative Vertebrate Anatomy: A laboratory Dissection Guide. New York: McGraw-Hill Education. pp. 71–72.

- Kardong, Kenneth (1995). Vertebrate: Comparative Anatomy, Function, Evolution. New York: McGraw-HIll. pp. 215–225. ISBN 9780078023026.

- Xiong, Jianli (2014). "Comparison of vomerine tooth rows in juvenile and adult Hynobius guabangshanensis". Vertebrate Zoology. 64: 215–220.

- Xiong, Jianli (2014). "Comparison of vomerine tooth rows in juvenile and adult Hynobius guabangshanensis". Vertebrate Zoology. 64: 215–220.

External links

- Mudpuppy (Necturus maculosus), Natural Resources Canada