Cockpit display system

The Cockpit display systems (or CDS) provides the visible (and audible) portion of the Human Machine Interface (HMI) by which aircrew manage the modern Glass cockpit and thus interface with the aircraft avionics.

History

Prior to the 1970s, cockpits did not typically use any electronic instruments or displays (see Glass cockpit history). Improvements in computer technology, the need for enhancement of situational awareness in more complex environments, and the rapid growth of commercial air transportation, together with continued military competitiveness, led to increased levels of integration in the cockpit.

The average transport aircraft in the mid-1970s had more than one hundred cockpit instruments and controls, and the primary flight instruments were already crowded with indicators, crossbars, and symbols, and the growing number of cockpit elements were competing for cockpit space and pilot attention.[1]

Architecture

Glass cockpits routinely include high-resolution multi-color displays (often LCD displays) that present information relating to the various aircraft systems (such as flight management) in an integrated way. Integrated Modular Avionics (IMA) architecture allows for the integration of the cockpit instruments and displays at the hardware and software level to be maximized.

CDS software typically uses API code to integrate with the platform (such as OpenGL to access the graphics drivers for example). This software may be written manually or with the help of COTS tools such as GL Studio, VAPS, VAPS XT or SCADE Display .

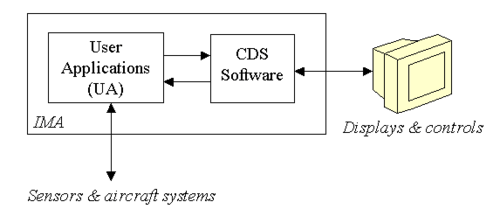

Standards such as ARINC 661 specify the integration of the CDS at the software level with the aircraft system applications (called User Applications or UA).

See also

- Acronyms and abbreviations in avionics

- Avionics software

- Integrated Modular Avionics

- ARINC 661

References

- Wallace, Lane. "Airborne Trailblazer: Two Decades with NASA Langley's 737 Flying Laboratory". NASA. Retrieved 2012-04-22.

Prior to the 1970s, air transport operations were not considered sufficiently demanding to require advanced equipment like electronic flight displays. The increasing complexity of transport aircraft, the advent of digital systems and the growing air traffic congestion around airports began to change that, however. She added that the average transport aircraft in the mid-1970s had more than 100 cockpit instruments and controls, and the primary flight instruments were already crowded with indicators, crossbars, and symbols. In other words, the growing number of cockpit elements were competing for cockpit space and pilot attention.