Cleveland Elementary School shooting (San Diego)

The Grover Cleveland Elementary School shooting took place on January 29, 1979, at a public elementary school in San Diego, California, United States. The principal and a custodian were killed; eight children and police officer Robert Robb were injured. A 16-year-old girl, Brenda Spencer, who lived in a house across the street from the school, was convicted of the shootings. Charged as an adult, she pleaded guilty to two counts of murder and assault with a deadly weapon, and was given an indefinite sentence. As of August 2020, she remains in prison.

| Grover Cleveland Elementary School shooting | |

|---|---|

| Location | San Diego, California |

| Coordinates | 32°47′48″N 117°00′41″W |

| Date | January 29, 1979 |

| Target | Students and faculty at Grover Cleveland Elementary School |

| Weapons | Ruger 10/22 semi-automatic .22 caliber rifle |

| Deaths | 2 |

| Injured | 9 |

| Perpetrator | Brenda Spencer |

A reporter reached Spencer by phone while she was still in the house after the shooting, and asked her why she had done it. She reportedly answered: "I don't like Mondays. This livens up the day,"[1][2] which inspired Bob Geldof and Johnnie Fingers to write the Boomtown Rats song "I Don't Like Mondays".[3]

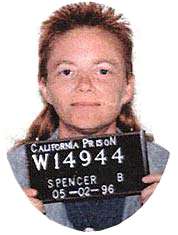

Brenda Spencer

Brenda Spencer | |

|---|---|

Spencer in 1996 | |

| Born | Brenda Ann Spencer April 3, 1962 San Diego, California |

| Status | Incarcerated |

| Years active | 7 |

| Criminal charge(s) | 2 counts of murder 1 count of assault with a deadly weapon |

| Criminal penalty | 25 years to life in prison |

| Parent(s) | Wallace Spencer Dot Spencer |

Brenda Spencer (born April 3, 1962) lived in the San Carlos neighborhood of San Diego, California, in a house across the street from Grover Cleveland Elementary School in the San Diego Unified School District. Age 16, she was 5'2" (157 cm) and had bright red hair.[4][5][6][7] After her parents separated, she lived with her father, Wallace Spencer, in poverty. They slept on a single mattress on the living room floor, with empty alcohol bottles throughout the house.[5][7]

Acquaintances said Spencer expressed hostility toward policemen, had spoken about shooting one and had talked of doing something big to get on television.[1][5] Although Spencer showed exceptional ability as a photographer, winning first prize in a Humane Society competition, she was generally uninterested in school. She attended Patrick Henry High School where one teacher recalled frequently inquiring if she was awake in class. Later, during tests while she was in custody, it was discovered Spencer had an injury to the temporal lobe of her brain. It was attributed to an accident on her bicycle.[8]

In early 1978, staff at a facility for problem students, into which Spencer had been referred for truancy, informed her parents that she was suicidal. That summer, Spencer, who was known to hunt birds in the neighborhood, was arrested for shooting out the windows of Grover Cleveland Elementary with a BB gun and for burglary.[1][9] In December, a psychiatric evaluation arranged by her probation officer recommended that Spencer be admitted to a mental hospital for depression, but her father refused to give permission. For Christmas 1978, he gave her a Ruger 10/22 semi-automatic .22 caliber rifle with a telescopic sight and 500 rounds of ammunition.[5][7] Spencer later said, "I asked for a radio and he bought me a gun." When asked why he might have done that, she answered, "I felt like he wanted me to kill myself." [7][10]

Shooting

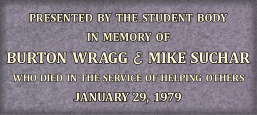

On the morning of Monday, January 29, 1979, Spencer began shooting at children waiting for Principal Burton Wragg (age 53) to open the gates to Grover Cleveland Elementary.[11] She injured eight children. Spencer shot and killed Wragg as he tried to help children. She also killed custodian Mike Suchar (age 56) as he tried to pull a student to safety.[5] A police officer (age 28), responding to a call for assistance during the incident, was wounded in the neck as he arrived.[5] Further casualties were avoided only because the police obstructed her line of fire by moving a garbage truck in front of her house.

After firing thirty times, Spencer barricaded herself inside her home for several hours. While there, she spoke by telephone to a reporter from The San Diego Union-Tribune, who had been randomly calling telephone numbers in the neighborhood. Spencer told the reporter she had shot at the schoolchildren and adults because, "I don't like Mondays. This livens up the day." She also told police negotiators the children and adults whom she had shot were easy targets and that she was going to "come out shooting."[5][2] Spencer has been repeatedly reminded of these statements at parole hearings.[12] Ultimately, she surrendered and left the house, reportedly after being promised a Burger King meal by negotiators.[5][7] Police officers found beer and whiskey bottles cluttered around the house but said Spencer did not appear to be intoxicated when arrested.[13]

Imprisonment

Spencer was charged as an adult and pleaded guilty to two counts of murder and assault with a deadly weapon. On April 4, 1980, a day after her 18th birthday, she was sentenced to 25 years to life.[14] In prison, Spencer was diagnosed as an epileptic and received medication to treat her epilepsy and depression. While at the California Institution for Women in Chino, she worked repairing electronic equipment.[7][15]

Under the terms of her indeterminate sentence, Spencer became eligible for hearings to consider her suitability for parole in 1993. Normally, very few people convicted on a charge of murder were able to obtain parole in California before 2011.[16] As of December 2015, she has been unsuccessful at four parole board hearings. At her first hearing, Spencer said she had hoped police would shoot her and that she had been a user of alcohol and drugs at the time of the crime, although the results of drug tests done when she was taken into custody were negative. In her 2001 hearing, Spencer first claimed that her father had been subjecting her to beatings and sexual abuse, but he said the allegations were not true. The parole board chairman said that as she had not previously told any prison staff about the allegations, he doubted whether they were true.[17] In 2005, a San Diego deputy district attorney cited an incident of self-harm from four years earlier when Spencer's girlfriend was released from jail, as showing that she was psychotic and unfit to be released.[15] The self-harm is commonly reported as scratching the words "courage" and "pride" into her own skin; however, Spencer corrected this during her parole hearing as "runes" reading "Unforgiven" and "alone". In 2009, the board again refused her application for parole and ruled it would be ten years before she would be considered again.[11][18] She is eligible for a Parole Suitability Hearing in September 2021.[19]

As of August 2020, she remains imprisoned at the California Institution for Women.[19]

Aftermath

A plaque and flagpole were erected at Cleveland Elementary in memory of the shooting victims. The school was closed in 1983, along with a dozen other schools around the city, due to declining enrollment.[20] In the ensuing decades, it was leased to several charter and private schools. From 2005 to 2017, it housed the Magnolia Science Academy,[21] a public charter middle school serving students in grades 6–8.[22]

On January 17, 1989, almost ten years after the events at San Diego's Grover Cleveland Elementary, there was another shooting at a school named Grover Cleveland Elementary, this one in Stockton, California. Five students were killed and thirty were injured. One survivor of the 1979 shooting described herself as "shocked, saddened, horrified" by the eerie similarities to their own traumatic experience.[23]

Media

Song

Bob Geldof, then the lead singer of the Boomtown Rats, read about the incident when a news story about it came off the telex at WRAS-FM, the campus radio station at Georgia State University in Atlanta. He was particularly struck by Spencer's claim that she did it because she did not like Mondays, and began writing a song about it, also incorporating the reporters' "Tell me why?," called "I Don't Like Mondays".[15] It was released in July 1979 and was number one for four weeks in the United Kingdom,[24] and was the band's biggest hit in their native Ireland. Although it did not make the Top 40 in the U.S., it still received extensive radio airplay (outside of the San Diego area) despite the Spencer family's efforts to prevent it.[3] Geldof has later mentioned that, "[Spencer] wrote to me saying 'she was glad she'd done it because I'd made her famous,' which is not a good thing to live with."[25]

Books

The 1999 book Babyface Killers: Horrifying True Stories of America's Youngest Murderers, authored by Clifford L. Linedecker dedicates the book's prologue to Spencer and refers to her crimes in multiple chapters.[26]

The 2008 book Ceremonial Violence: A Psychological Explanation of School Shootings, by Jonathan Fast, analyzes the Cleveland Elementary shooting and four other cases from a psychological perspective. These are the other shootings reported on: the Columbine High School shooting, the shootings at Simon's Rock College, the Bethel Regional High School shooting, and the Pearl High School shooting.[27]

Films

The 1982 Japanese-American documentary film The Killing of America depicts the incident.

Television

A 2006 television documentary about the event was titled I Don't Like Mondays.[28]

The Lifetime Movies, series Killer Kids released an episode "Deadly Compulsion" depicting Spencer's crimes, first air date: September 3, 2014.[29][30][31]

The Investigation Discovery network portrayed Spencer's crimes in one of the three cases presented in the premiere episode of season 2 on the crime documentary series Deadly Women, titled "Thrill Killers", first air date: October 9, 2008.[32][33][34]

References

- "School Sniper Suspect Bragged Of 'Something Big To Get On TV'". Evening Independent. Associated Press. January 30, 1979.

- Jones, Tamara (November 1, 1998). "Look back in sorrow: in 1979, a teenage girl opened fire on a suburban San Diego elementary school; today, as the nation reels from a rash of similar tragedies, the survivors still struggle to understand why it happened". Good Housekeeping. Archived from the original on May 16, 2011.

- Steve Clarke (October 18–31, 1979). The Fastest Lip on Vinyl. Smash Hits. EMAP National Publications Ltd. pp. 6–7.

- Paul Jacobs; Nancy Skelton (January 30, 1979). "Girl Sniper Kills 2, Wounds 9 at San Diego School". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on March 27, 2016.

- "Sniping suspect had a grim goal". The Milwaukee Journal. January 29, 1979. p. 4.

- Laura Finley (2011). Encyclopedia of School Crime and Violence (1st ed.). ABC-CLIO. p. 454. ISBN 978-0-313-36239-2.

- Böckler et al. 2013, p. 257.

- Böckler et al. 2013, pp. 251-253.

- "Classmates Say Alleged Sniper Seemed Lonely, Friendless Girl". Washington Post. January 31, 1979. Retrieved November 3, 2017.

- "Brenda Spencer". The Fliegen.

- "School Shooter Brenda Spencer Denied Parole". KFMB-TV. August 14, 2009. Archived from the original on September 1, 2010.

- Böckler et al. 2013, p. 250; Böckler et al. 2013, p. 257.

- "Brenda-Spencer". Sdpolicemuseum.com.

- "School rifle attack nets 25 years to life". Edmonton Journal. April 5, 1980. Retrieved June 25, 2018.

- Jay Allen Sanford (March 10, 2005). "Brenda Spencer was 16". San Diego Reader.

- "In California, Victims' Families Fight for the Dead". The New York Times. August 19, 2011.

- Böckler et al. 2013, p. 248.

- "Parole denied in school shooting". usatoday30.usatoday.com. USA TODAY. Associated Press. June 19, 2007. Retrieved December 26, 2016.

- "State of California Inmate Locator". CDCR Inmate Locator. California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation. Retrieved September 27, 2018. CDCR no. W14944.

- Swain, Liz (March 26, 2015). "She didn't like Mondays, they don't want plaque moved". San Diego Reader. Retrieved November 2, 2017.

- "Tragic past, uncertain present, bright future of Cleveland Elementary". Mission Times Courier. December 18, 2015.

- "Home page". Magnolia Science Academy. Archived from the original on February 18, 2012. Retrieved August 26, 2016.

- Michael Granberry (January 19, 1989). "Victims of San Diego School Shooting Are Forced to Cope Again 10 Years Later". Los Angeles Times.

- "I Don't Like Mondays". Official Charts Company. July 21, 1979.

- Bob Geldof reveals the truth of "I Don't Like Mondays"!. Event occurs at 2:08. Retrieved November 7, 2017.

- Linedecker, Clifford L. (December 15, 1999). Babyface Killers: Horrifying True Stories of America's Youngest Murderers. New York, N.Y.: St. Martin's Paperbacks. ISBN 9780312970321.

- Jonathan Fast (September 4, 2008). Ceremonial Violence: A Psychological Explanation of School Shootings. The Overlook Press. ISBN 9781590200476.

- "I Don't Like Mondays (TV 2006)". IMDb.

- "Watch Deadly Compulsion Full Episode - Killer Kids | Lifetime". Lifetime. A&E Television Networks. September 3, 2014. Archived from the original on September 19, 2018. Retrieved November 2, 2017.

- "Killer Kids: Deadly Compulsion". TV.com. CBS Interactive. September 3, 2014. Retrieved November 2, 2017.

- "Killer Kids - Season 3 Episode 19 Deadly Compulsion". Dailymotion. Dailymotion. November 24, 2015. Retrieved November 2, 2017.

- "Thrill Killers | Deadly Women". www.investigationdiscovery.com. Discovery Communications, LLC. October 8, 2008. Retrieved November 2, 2017.

- "Deadly Women | Season 2 Episode 1 Thrill Kills". Dailymotion. Retrieved November 2, 2017.

- "Deadly Women - Season 2 Episodes List". next-episode.net. October 9, 2008. Retrieved November 2, 2017.

Further reading

- Böckler, Nils; Seeger, Thorsten; Sitzer, Peter; Heitmeyer, Wilhelm (2013). School Shootings: International Research, Case Studies, and Concepts for Prevention (1st ed.). Springer Science+Business Media. ISBN 978-1-461-45526-4.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

Videos:

- "40 Years Ago, Brenda Spencer Took Lives At Elementary School". San Diego Union-Tribune. January 30, 2019.

- "1993: Convicted school shooter Brenda Spencer speaks with San Diego's News 8 - PART 1". CBS 8 San Diego. June 13, 2019.

- "1993: Convicted school shooter Brenda Spencer speaks with San Diego's News 8 - PART 2". CBS 8 San Diego. June 13, 2019.

- "1993: Convicted school shooter Brenda Spencer speaks with San Diego's News 8 - PART 3". CBS 8 San Diego. June 13, 2019.

- "1993: Convicted school shooter Brenda Spencer speaks with San Diego's News 8 - PART 4". CBS 8 San Diego. June 13, 2019.