Clean climbing

Clean climbing is rock climbing techniques and equipment which climbers use in order to avoid damage to the rock. These techniques date at least in part from the 1920s and earlier in England, but the term itself may have emerged in about 1970 during the widespread and rapid adoption in the United States and Canada of nuts (also called chocks), and the very similar but often larger hexes, in preference to pitons, which damage rock and are more difficult and time-consuming to install.[1] Pitons were thus eliminated in North America as a primary means of climbing protection in a period of less than three years.

Due to major improvements in equipment and technique, the term clean climbing has come to occupy a far less central, and somewhat different, position in discussions of climbing technology, compared with that of the brief and formative period when it emerged four decades ago.

Rock preservation

Drilled and hammered equipment such as bolts, pitons, copperheads and others scar rock permanently. Around 1970, various protection devices that were far less likely to damage rock and much faster and easier to install became widely available. Such "clean" gear, as of contemporary times, now include spring-loaded camming devices, nuts and chocks, and slings, for hitching natural features.

Contemporary alternatives to pitons, which used to be called "clean climbing gear", have made most routes safer and easier to protect, and have greatly contributed to a remarkable increase in the standards of difficulty notable since about 1970. Pitons are now regarded as highly specialized equipment, needed by a small minority of climbers interested in routes of peculiar difficulty.

Even clean gear can damage rock, if the rock is very soft or if the hardware is impacted with substantial force. A falling climber's energy can drive a camming device's lobes outward with great force. This can carve grooves into the rock's surface, or, if the cam is in a crack behind a flake, the expansion can loosen the flake and eventually (or suddenly) split it off. Wedges (nuts) can also be forced into a crack much harder than the leader intended, and cracks have been damaged as cleaners try to chisel or pull stuck nuts out of their constrictions. In very soft rock, nuts and cams both can blow right through the rock and out of their placements, even with forces as small as those generated by tugging to "set" the piece. Although hooks are often categorized as clean, they easily damage soft rock and can even damage granite.

History

Morley Wood during the ascent of Pigott's Climb on Clogwyn Du'r Arddu (North Wales) in 1926 reportedly was the first climber to use pebbles slung with rope for protecting a rock climb. These were replaced by the use of machine nuts in England during the 1950s.

In 1961, John Brailsford of Sheffield, England, reportedly was the first to manufacture nuts specifically for climbing.[2]

Rock scarring caused by pitons was an important impetus for the emergence of the term, and the initial reason climbers largely abandoned pitons. However, today what was in the 1970s called "clean protection" and regarded by many climbers of the day with some suspicion with regard to safety, is now recognized as a faster, easier, more efficient and safer means of protecting most climbing routes than pitons- which are now, in comparison with the 1960s, rarely used.

When chrome molybdenum steel pitons replaced softer iron in the early 1960s, pitons became more easily removable, resulting in their more intensive use and alarming damage to increasingly popular climbing routes. In response, there was a "movement" among U.S. climbers around 1970 to eliminate their use.

Although bolts continue to be used today for sport climbing, and aid climbers, rescuers and occasionally mountaineers may employ pitons, bolts and a variety of other hammered techniques, the average free climber today has no experience with hammering or drilling. Prior to the introduction of spring-loaded camming devices (in about 1980), clean climbing involved a safety trade-off in certain situations. Protection methods of today, however, are generally seen as faster, safer and easier than those of the piton era, and average run-outs between gear placements have probably become shorter on many routes.[3]

Although English climbers had long used stones wedged into cracks and slung with cord for protection, this practice was rare in the U.S. In 1967, Royal Robbins returned from England with a sampling of artificially manufactured chock stones. He promptly made the first ascent of the Nutcracker in Yosemite Valley using exclusively these wedges. He wrote about this six-pitch climb and others in Summit magazine and the American Alpine Journal but without much obvious immediate influence.[4]

Within several years, another well-known Yosemite climber, Yvon Chouinard, began to commercially manufacture metal chocks, or nuts, in California. An important milestone occurred with the 1972 Chouinard Equipment Catalog, which included two articles on environmental concerns and climbing gear. One was written by Chouinard and Tom Frost; another was by Doug Robinson titled "The Whole Natural Art of Protection".[5] Around this time, Bill Forrest also produced a somewhat less successful range of passive chocks, more successful were his experiments with camming which went on to become the first Lowe Alpine System active camming devices (sometimes jokingly called "crack jumars").

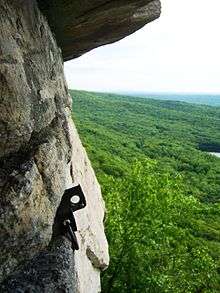

Many other prominent climbers of the era, including John Stannard at the Shawangunks in New York, were influential participants in this early 1970s movement. As a result, climbers en masse rapidly adopted the technique, pitons quickly fell from favor, and the switch to "clean climbing" constituted a landmark change in the sport of rock climbing.[6][7]

Conditions today

Piton scars from an earlier era are still widely visible. Today, on a relative handful of long-established climbing routes in a few places, these old scars enable the use of clean hardware. Such hardware would have been less useful on these particular routes before the rock was altered. Some routes which had been only ascendable on aid "go free" today for the same reason: there are in some places cracks smaller than fingertips which can now be climbed without aid because piton scars provide holds which didn't previously exist.[8]

Values and regulation

Most rock climbing, both long before and immediately after the development of "clean climbing", would now be classified as traditional climbing in which protection was installed and removed by each successive party on a given route. However, the term "trad climbing" only arose later, to describe that which is not sport climbing, a comparatively recent activity in which all protective gear is permanently and abundantly fixed on certain routes.

Fixed gear certainly existed in 1970 as it does now. Some contemporary routes, like a number of long, limestone climbs in the Bow Valley, Alberta, are notable for fixed bolts at belay stances and for protection at relatively wide intervals,[9] and thus a kind of hybrid of trad and sport is possible—if supplementary gear can be placed. Perhaps the most extreme example of acceptable non-"clean climbing" is the many via ferrata mountaineering routes, of primarily the Alps.

A relatively small number of climbers believe in varying degrees that fixed gear should never be placed on any route in order to preserve the rock and its inherent challenges.[10][11] This long-standing cultural question of doctrine is largely separate from issues that gave rise to the term "clean climbing."

Some climbing areas, notably some of the national parks of the United States, have de jure regulations about whether, when and how hammer activity may be employed. For example, drilling is not banned in Yosemite, but power drills are. Other areas have de facto local ethics prohibiting certain activity. For example, bolting is not banned in Pinnacles National Park, but the local climbing community does not tolerate rap-bolting — bottom-up route development is expected.

References

- "nutcracker"

- Chouinard 1972 Catalog

- Freedom of the Hills, 7th Edition, p. 273

- Ascent Notes for: Northeast Face - 5.7 Retrieved 2009-09-30

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2009-10-11. Retrieved 2009-07-12.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2009-02-18. Retrieved 2009-02-03.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- Peter Livesey Climber and Hillwalker magazine article