Clayoquot protests

The Clayoquot protests also called War in the Woods were a series of protests related to clearcutting in Clayoquot Sound, British Columbia and culminated in the mid-1993, when 900 people were arrested. As of 2017 the protest against logging of the temperate rainforest has been the largest act of civil disobedience in Canadian history.[1]

The timber resources of Clayoquot Sound attracted growing numbers of foreigners, limiting access of indigenous peoples to land and creating increasing displeasure among the local population. In the 1980s and 1990s, government support of private company resource extraction allowed for the growth of this industry over time, resulting in the presence of logging companies in Clayoquot Sound [2] The differing opinions between these groups led the First Nations to develop lobbying organizations and a series of negotiations over logging practices. In the late 1980s, the situation escalated when MacMillan Bloedel secured a permit to log Meares Island.[3]

From 1980 to 1994 several peaceful protests and blockades of logging roads occurred, with the largest in the mid-1993, when over 800 protesters were arrested and many put on trial.[4] Protesters included local residents of the Sound, the Tla-o-qui-aht First Nation and Ahousaht First Nation bands, and environmentalist groups such as Greenpeace and Friends of Clayoquot Sound.[5]

The logging protests and blockades received worldwide mass media attention, creating national support for the environmental movement in British Columbia and fostering strong advocacy for anti-logging campaigns. Media focused on the mass arrests of people engaging in peaceful protests and blockades, aggression and intimidation from law enforcement, which served to strengthen public support for nonviolent protests.[6]

Background

The region had been populated by Indigenous communities for millennia before the arrival of colonial European explorers in the 18th century. In 1774, the first European to arrive in Tofino was Spaniard Juan José Pérez Hernández. Hernández and his crew recognized the potential wealth of the region's resources, such as fish and timber. Afterwards, several trading posts were erected and operated for a little over a century. In 1899, the first Catholic mission was built. Over time, the region's prosperity fluctuated similarly to many other frontier settlements, due to difficulty accessing the region from a lack of roads. In 1959, a logging road was built to Tofino, marking the beginning of the region's commercial exploitation of resources. This allowed the fishing industry to take off and by 1964, four hundred boats were tied up at the Tofino Harbor at once.

On May 4, 1971 an official dedication ceremony created Pacific Rim National Park in Clayoquot Sound. As a result, the 1959 logging road was paved in order to access Tofino. Prior to this, logging companies had been investing into the region: with easier access, natural resources could now be exploited on a larger scale. As timber supply in the small operations in the Kennedy Lake and Ucluelet area began to diminish the logging companies' presence near Tofino increased.[7]

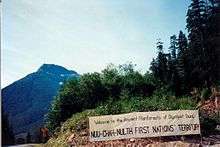

Beginning in the 1980s, what was considered 'unrestricted logging' provoked significant public protests. It began when MacMillan Bloedel announced to begin logging on Meares Island. Leaders of the Nuu-chah-nulth tribe rejected this proposal. In 1984, MacMillan Bloedel workers arrived at Meares Island where they were met by the Nuu-chah-nulth, local environmentalists and other supporters blockading the road. To prevent logging operations from continuing, protesters declared the island a Tribal Park. MacMillan Bloedel attempted to override this with a court injunction, succeeding in their aims. However, in 1985 the Ahousaht and Tia-o-qui-aht First Nations acquired their own injunction to halt logging on the island, at least until the Nuu-chah-nulth's concerns had been addressed in the form of a treaty. Similar protests continued to run into the late 1980s and throughout Clayoquot Sound.[8]

These protests posed difficulties for locals who worked in the lumber industry. The blockades prevented these workers from completing their jobs, which meant they would not be paid. In 1988, the Tin Wis Coalition was created allowing workers, environmentalists, and aboriginals to discuss mutually beneficial changes. In October 1990 the coalition ceased shortly after a conference.

In 1989 a new forum of eleven-members formed, which meant to produce more results and resolutions by finding compromises for land use in Clayoquot Sound to satisfy all stakeholders. It was formed by the Social Credit government in BC, but in October 1989 it disbanded similarly to the prior coalition.

In 1990, the Clayoquot Sound Development Steering Committee, with representatives from the logging industry, environmentalists, tourist operators, and First Nations groups formed and talked for over a year and a half until environmentalists and tourism representatives walked out, unimpressed that logging operations had continued while the groups met, and disbanded in May 1991.

The government and a separate panel of Ministry of Environment and Ministry of Forests representatives met to decide where logging could and could not occur, while the Steering Committee was gathering. In May 1991 environmentalists left for the second time failed to reach an agreement. In 1991, the British Columbia New Democratic Party (NDP) took up government and utilized all the information compiled from both the committee and the task force to create their Clayoquot Sound Land Use Plan, which they announced in 1993.[9] The plan divided the forests of Clayoquot Sound into numerous regions, setting parts aside for preservation, logging, and other various activities including recreation, wildlife, and scenery.[10] The plan permitted logging in two-thirds of the old growth forest in Clayoquot.[11]

Blockades and protests

In 1984, the first opposition to logging companies in the Sound occurred, when members of Friends of Clayoquot Sound and First Nations groups set up blockades on the logging roads leading to Meares Island. The island was important to First Nations communities because it was the main source of drinking water for the area.[12]

Environmental groups like Friends of Clayoquot Sound and the First Nations communities were concerned with the logging companies' approach to resource management. The First Nations did not completely oppose all logging in the Sound; in fact, they acknowledged that their people had depended on the land's resources for centuries.[13] Rather, they opposed the fact that the companies were pursuing short-term profits by extracting resources at maximum efficiency rates, with little interference from the British Columbia government.[14]

When Macmillan-Bloedel workers arrived at Meares Island in 1984, they encountered a bigger blockade that included members of the Nuu-chah-nulth tribe, local environmental groups, and other supporters of their cause.[14] Throughout the 1980s animosity continued between these groups due to each side's respective injunctions, which were in contradiction with one another over the use of the land.

In 1992, Friends of Clayoquot Sound set up another blockade.

In mid-1993, the most significant protests occurred. Introduction of the Clayoquot Sound Land Use Plan sparked outrage among environmentalists and the Nuu-chah-nulth people alike. Environmental groups debated the amount and type of land that had been divided, but the First Nations, who composed almost the entire population of the Sound, were concerned that the plan did not consider their spatial, environmental, or economic practices.[15]

During the mid-1993, nearly 11,000 people came to Clayoquot Sound to take part in the protests.[16] Activists eventually gained the support of major organizations such as Greenpeace and the Sierra Club.[17] Every day for three months, protesters would gather and blockade a remote logging road, preventing vehicles carrying workers from reaching their sites. The Royal Canadian Mounted Police would then read a court injunction and carry or drag protesters into a bus, which would transport them to the police station in Ucluelet to be charged and released. By the middle of the year, the sheer number of people that had been arrested made it one of the largest acts of civil disobedience in Canadian history.[18]

Many residents of Tofino and Ucluelet worked in the logging industry and felt that the 1993 protests threatened their livelihood. In response, they organized a counter-protest called the "Ucluelet Rendezvous '93." More than 5,000 people came to support the workers and logging community, culminating in 200 litres (44 imp gal; 53 US gal) of human excrement being poured near the environmentalists' information site . Loggers stated that they did not want to wipe out the forests, but that carrying on the industry was economically important for future generations.[19]

Media and protest attention

Through local, national, and international news coverage, the demonstrations in the Clayoquot Sound became recognized by the public as having the potential to make significant changes to environmental policy.[20] The logging protests and blockades received worldwide mass media attention, creating national support for environmental movements facing British Columbia and fostering a strong advocacy for anti-logging campaigns.[6]

Mass media attention began by relaying highly controversial, and at times, violent coverage of the protest events, showcasing dramatic outcomes that would lead to higher viewing and readership rates. Reporters believed that this sort of coverage was necessary to bring attention to the cause (given the outcome of certain protests) and offered more appeal to a public that sought entertainment value in the media. Females were portrayed more often than men as being 'radical activists' and members of extremist groups, which encouraged the formation of social stigmas being attached to female protesters.[20] The media's creation of stereotypes led to controversy surrounding the potential economic benefits for media outlets publishing sensational news. Accusations began to surround the mass media's use of language as being biased and one-sided when referring to relevant multi-stakeholder groups.[21]

Over time, the media began to detract attention from 'radical activists' towards reports on individuals who were indirectly involved in the protests. The opinions of 'mild activists' were covered more frequently over time due to their moderation. Considering the ongoing nature of the protests, a shift was made in the media in hopes of resolving the underlying issues surrounding Clayoquot Sound. News articles began to steer reports away from extremists who, in the past, were the focus of dramatic and uniquely portrayed events. Reporters indicated that they chose to interview more moderate groups and 'mild activists' because they were believed to offer more credible and sensible information. The drive to produce more reliable information surpassed the media's need to provide entertainment, which encouraged the public to understand the seriousness behind the issue taking place.[20]

Media attention began to focus on the perceived unfairness of the mass arrests after individuals joined in peaceful protests and blockades, violating a court injunction that forbid the occurrence of such events. News sources focused on activists as having encountered on-site aggression and intimidation, which eventually helped strengthen public support for non-violent actions. Eventually the media did not emphasize the significance of any few particular environmental leaders as central actors in the protection of Clayoquot Sound. Instead, protesters, environmental NGOs and local First Nations were portrayed together as being deeply committed to the effort of preserving Clayoquot Sound, becoming a symbol for international environmental efforts and awareness. These lobby groups, advocating for the boycott of large-scale logging corporations, successfully urged the public to join in and support the cause as activists themselves.[6]

Trials

In August 1994, the trials began and continued for five weeks in front of the BC Provincial court, with BC Supreme Court Justice John Bouck overseeing the first round of prosecutions.[22] Numerous people from a variety of backgrounds and ages were arrested daily.[23] Those arrested for participating in the protests were charged with criminal contempt of court for defying an injunction banning demonstrations on company work sites. The injunction was obtained by Macmillan Bloedel Ltd.'s logging operations at the Kennedy Lake Bridge, near Clayoquot Sound, stating that no public interference was to be allowed in the areas they were logging.[23] Of the 932 people arrested, 860 were prosecuted in eight trials. All those prosecuted for criminal intent were found guilty.[24]

The outcomes of the trials varied tremendously depending on the ways in which individuals were involved and if people were first-time offenders. Penalties included fines, probation and jail sentences. The range of jail terms was suspended sentences to up to six months in jail, while fines ranged from $250 to $3,000. The judges included Justice Bouck, Low, Murphy, and Oliver. The lightest sentences were given out by Justice Drake in December, which gave those found guilty no jail time and $250 fines. The first 44 people to be put on trial in front of John Bouck received jail time ranging from 45 to 60 days, and fines of $1,000 to $3,000.[25] Justice Low judged the second group with penalties of 21 days in jail or home arrest with a security bracelet for electric monitoring during probation, in some cases allowing a choice between home arrest or jail. Many who had the choice decided to do their sentences in jail as an added protest to the issue.[26]

Aftermath

The intact forests that stand in Clayoquot Sound today represent the outcome of numerous protests that occurred at the end of the 20th Century, having established a solid protection plan for forests. Greenpeace played a significant role in these protests, instigating a boycott of BC forest products in order to apply pressure on the industry. The boycott was called off once the scientific panel's recommendations were accepted by the government, deferring logging until an inventory of pristine areas was completed. The Annual Allowable Cut and clear-cuts in the area were reduced to a maximum of four hectares. In addition, Eco-Based Planning was to occur once biological and cultural inventories were completed.[27]

In July 1995, the first significant change in government policies occurred, when all 127 unanimous recommendations made by the scientific panel on Clayoquot Sound were accepted by the Forests Minister of British Columbia, Andrew Petter, and the Environment Minister, Elizabeth Cull on behalf of the NDP government.[28]

In 1996, the provincial government financed the compromise, extending $9.3 million over three years to MacMillan Bloedel "to log the territory in an ecologically sound way".[29]

As the protests had a negative impact on the reputation and sales of large-scale logging companies in Clayoquot Sound, they removed their operations from the area, and First Nations residents in the Sound were then able to purchase 50% of ownership in the region's logging rights. Iisaak Forest Resources Ltd. formed on behalf of the First Nations, allowing them to take charge over logging operations with their private company.[30] In 1993 environmental lawyer Robert Kennedy Jr. had suggested that aboriginal people should be given full control of forest resources.[29]

In 1999, Iisaak Forest Resources Ltd. signed an agreement known as a Memorandum of Understanding (MOU), ensuring that logging would not occur outside areas which had obviously been logged before and which were outside the intact ancient forests of Clayoquot Sound.[30][31]

In 2000, the entire Sound was designated as a Biosphere Reserve by UNESCO, further emphasizing its ecological importance; however, this was not legally binding in preventing companies from logging in the future.[32] The designation created world recognition of Clayoquot Sound's biological diversity, and a $12M monetary fund to "support research, education and training in the Biosphere region".[33]

At the end of July 2006, a new set of Watershed Plans was approved in Clayoquot Sound, opening the door for logging to proceed a further 90,000 hectares in the forest, including pristine old-growth valleys[34][35][36]

As of 2007, both logging tenures within Clayoquot Sound are controlled by first nation logging companies.[37] Iisaak Forest Resources controls Timber Forest License (TFL) 57 in Clayoquot Sound.[38][39] MaMook Natural Resources Ltd, in conjunction with Coulson Forest Products, manages TFL54 in Clayoquot Sound.[40][38]

In 2013, the War in the Woods was said to have set the stage for the protests around the two big pipeline proposals in BC.[29]

References

- The Canadian Encyclopedia. Clayoquot Sound. Historica Dominion. Retrieved on: November 8, 2012.

- Guppy, Walter (1997). Clayoquot Soundings: A History of Clayoquot Sound, 1880s-1980s. Tofino, British Columbia: Grassroots Publication. pp. 7, 55, 66. ISBN 0-9697703-1-6.

- Goetze, Tara C. (2005). "Empowered Co-Management: Towards Power-Sharing and Indigenous Rights in Clayoquot Sound, BC". Anthropologica. 47 (2): 251, 252. JSTOR 25606239.

- Goetze, Tara C. (2005). "Empowered Co-Management: Towards Power-Sharing and Indigenous Rights in Clayoquot Sound, BC". Anthropologica. 47 (2): 252–253. JSTOR 25606239.

- "Clayoquot Land Use Decision, 1993". Archived from the original on March 2, 2012. Retrieved March 13, 2012.

- Walter, P. "Adult Learning in New Social Movements: Environmental Protest and the Struggle for the Clayoquot Sound Rainforest." Adult Education Quarterly 57.3 (2007): 248-63.

- Guppy, Walter (1997). Clayquot Soundings: A History of Clayoquot Sound, 1880s-1980s. Tofino: Grass Roots Publications.

- Goetze, Tara C. (2005). "Empowered Co-Management: Towards Power-Sharing and Indigenous Rights in Clayoquot Sounds, BC". Anthropologica. 47 (2): 247–265. JSTOR 25606239.

- Harter, John-Henry (Fall 2004). "Environmental Justice for Whom? Class, New Social Movements and the Environment: A Case Study of Greenpeace Canada, 1971-2000". Labour / Le Travail. 54: 83–119. doi:10.2307/25149506. JSTOR 25149506.

- Braun, Bruce (2002). The Intemperate Rainforest: Nature, Culture, and Power on Canada's West Coast. Minneapolis, Minnesota: University of Minnesota Press. pp. 1–7. ISBN 978-0-8166-3399-9.

- UVIC: VI-Wilds: Clayoquot Sound; Vulnerable Ecosystems, http://icor.uvic.ca/viwilds/ve-clayoquot.html Archived October 21, 2009, at the Wayback Machine

- Langer, Valerie. "Clayoquot Sound: Not Out of the Woods Yet!". Common Ground Publishing Corp. Archived from the original on May 31, 2012. Retrieved March 27, 2012.

- Harkin, Michael E. (2000). "Sacred Places, Scarred Spaces". Wíčazo Ša Review. 15 (1): 56–57. JSTOR 1409588.

- Goetze, Tara C. (2005). "Empowered Co-Management: Towards Power-Sharing and Indigenous Rights in Clayoquot Sound, BC". Anthropologica. 47 (2): 252. JSTOR 25606239.

- Braun, Bruce (2002). The Intemperate Rainforest: Nature, Culture, and Power on Canada's West Coast. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press. p. 7. ISBN 0-8166-3399-1.

- Harter, John-Henry (2004). "Environmental Justice for Whom? Class, New Social Movements, and the Environment: A Case Study of Greenpeace Canada, 1971-2000". Athabasca University Press. 54: 108. JSTOR 25149506.

- Great Wilds Spaces: Clayoquot Sound; Flores and Vargas Island Provincial Parks, http://www.greatwildspaces.org/clayoquot.html Archived March 2, 2012, at the Wayback Machine

- Braun, Bruce (2002). The Intemperate Rainforest: Nature, Culture, and Power on Canada's West Coast. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota. pp. 1–2. ISBN 0-8166-3399-1.

- Harter, John-Henry (2004). "Environmental Justice for Whom? Class, New Social Movements, and the Environment: A Case Study of Greenpeace Canada, 1971-2000". Athabasca University Press. 54: 110. JSTOR 25149506.

- Malinicka, T., Tindallb, D.B., Dianic, M. "Network centrality and social movement media coverage: A two-mode network analytic approach." Department of Sociology and Department of Forest Resources Management: ScienceDirect. University of British Columbia (2011).

- http://search.proquest.com/docview/214888035

- Passoff, Michael (Winter 93/94). "Clayoquot protests put British Columbia on trial". Earth Island Journal. 9 (1). Check date values in:

|date=(help) - MacIsaac; Champagne, Ron; Anne (1994). Clayoquot Mass Trials: Defending the Rainforest. Gabriola Island: New Society Publishers. pp. xi.

- Ceric, Irina (2009). "Clayoquot Sound". International Encyclopedia of Revolution and Protest: 785.

- MacIsaac; Champagne, Ron; Anne (1994). Clayoquot Mass Trials: Defending the Rainforest. Gabriola Island: New Society Publishers. p. 162.

- MacIsaac; Champagne, Ron; Anne (1994). Clayoquot Mass Trials: Defending the Rainforest. Gabriola Island: New Society Publishers. p. 176.

- Harter, John-Henry (2004). "Environmental Justice for Whom? Class, New Social Movements, and the Environment: A Case Study of Greenpeace Canada, 1971-2000". Labour / Le Travail. 54: 113. doi:10.2307/25149506. JSTOR 25149506.

- Harter, John-Henry (2004). "Environmental Justice for Whom? Class, New Social Movements, and the Environment: A Case Study of Greenpeace Canada, 1971-2000". Labour / Le Travail. 54: 112. doi:10.2307/25149506. JSTOR 25149506.

- Kim Nursall Twenty years later, the “War in the Woods” at Clayoquot Sound still reverberates across B.C. Canadian Press, August 11, 2013

- "Clayoquot Sound Backgrounder". WC WC Victoria. Archived from the original on December 9, 2013. Retrieved February 21, 2013.

- "Clayoquot River Valley". Friends of Clayoquot Sound. Archived from the original on January 29, 2012. Retrieved February 21, 2013.

- Grant, Peter. "Clayoquot Sound". The Canadian Encyclopedia.

- British Columbia; Ministry of Forests and Range, http://www.for.gov.bc.ca/dsi/Clayoquot/clayoquot_sound.htm

- August, Denise (August 10, 2006). "Clayoquot Sound watershed plans released: War of the Woods II averted". West Coast Aquatic. Archived from the original on July 6, 2011. Retrieved December 9, 2009.

- CBC: Environmentalists angry over new logging in Clayoquot Sound: 2006, https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/environmentalists-angry-over-new-logging-in-clayoquot-sound-1.598604

- The Vancouver Sun (August 9, 2006). "Eco-logging deal in the works for Clayoquot Sound". Canada.com. Archived from the original on October 23, 2010. Retrieved December 16, 2009.

- Wilderness Committee: Clayoquot Sound, http://wc-zope.emergence.com:8080/WildernessCommittee_Org/campaigns/wildlands/clayoquot%5B%5D

- "Logging - Factsheet". Friends of Clayoquot Sound. Archived from the original on January 11, 2010. Retrieved December 16, 2009.

- Iisaak Forest Resources: http://www.iisaak.com/operations.html Archived March 3, 2016, at the Wayback Machine

- "Coulson Forest Products". The Coulson Group. Archived from the original on August 15, 2009. Retrieved December 16, 2009.