City of London swords

The City of London swords are five two-handed ceremonial swords owned by the City of London, namely the Mourning (or Black) Sword, the Pearl Sword, the State (or Sunday) Sword, the Old Bailey Sword and the Mansion House Justice Room Sword. A sixth sword, the Travelling Sword of State, replaces the Sword of State for visits outside the City. They are part of the plate collection of Mansion House, the official residence of the Lord Mayor of London.

Mourning Sword

The Mourning Sword is used on occasions of ceremonial mourning and has also been known as the Black Sword and the Lenten Sword. Its history is somewhat uncertain—The Telegraph reports that it is believed to be 16th century and that there is a rumour that it was found in the River Thames, but there has been more than one Mourning Sword through time.[1]

Samuel Pepys describes in his diary entry for 2 September 1663 a conversation with the then-Lord Mayor Anthony Bateman as follows:

After dinner into a withdrawing room; and there we talked, among other things, of the Lord Mayor's sword. They tell me this sword, they believe, is at least a hundred or two hundred years old; and another that he hath, which is called the Black Sword, which the Lord Mayor wears when he mournes, but properly is their Lenten sword to wear upon Good Friday and other Lent days, is older than that.

In his footnote to that entry in his 1893 transcription, Henry Benjamin Wheatley quotes William St John Hope, assistant secretary of the Society of Antiquaries, who had read a paper on the history of the insignia of the City of London to the society on 28 May 1891,[3] as saying "It has long been the custom in the City as in other places to have a sword painted black and devoid of ornament, which is carried before the Lord Mayor on occasions of mourning or special solemnity. ... The present mourning sword has an old blade, but the hilt and guard, which are of iron japanned black, are of the most ordinary character and seemingly modern. The grip and sheath are covered with black velvet."[4]

In Ceremonial Swords of Britain: State and Civic Swords (2017), Edward Barrett dates the current Mourning Sword to 1615 or 1623. It has a blade 3 ft 2 3⁄8 in (0.975 m) long and 1 7⁄8 in (4.8 cm) wide, and a 12 in (30 cm) hilt. While the velvet on the scabbard looks black, it is actually very deep maroon.[5]

The Mourning Sword was carried by then-Lord Mayor Roger Gifford at the funeral of Margaret Thatcher in 2013, leading the Queen and Prince Philip in and out of St Paul's Cathedral for the ceremony. It had not previously been used at a funeral since the state funeral of Sir Winston Churchill in 1965.[1] In addition to its use at funerals, it is used on Good Friday, feast days and the anniversary of the Great Fire of London.[5]

Pearl Sword

According to tradition, the Pearl Sword was presented to the City of London Corporation by Elizabeth I of England in 1571[lower-alpha 1] on the occasion of the opening of the Royal Exchange. There are approximately 2,500 pearls on the sword's scabbard, from which it gets its name.[7] In his footnote to the Diary of Samuel Pepys, Wheatley quotes Hope as saying that it is a "fine sword said to have been given to the city by Queen Elizabeth on the occasion of the opening of the Royal Exchange in 1570."[lower-alpha 1] but continues: "There is, however, no mention of such a gift in the City records, neither do Stow nor other old writers notice it. The sword is certainly of sixteenth century date, and is very possibly that bought in 1554, if it be not that "verye goodly sworde" given by Sir Ralph Warren in 1545."[4]

Its blade is 3 ft (0.91 m) long and 1 3⁄4 in (4.4 cm) wide, and it has a 10 3⁄4 in (27 cm) hilt. It weighs 4 lb 6 3⁄4 oz (2.01 kg) without the scabbard. The first 20 1⁄2 in (52 cm) of the blade have been blued and etched with images of fruit, trophies of arms, a quiver of arrows, the city arms and a ship at sail. Its scabbard dates back to at least 1808.[8]

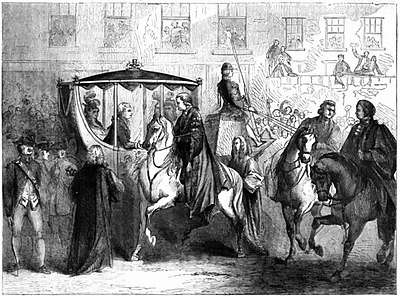

When the Queen comes to the City in State, she is ceremonially welcomed at the boundary with Westminster, where Temple Bar used to be, by the Lord Mayor of London, who offers her the hilt of the Pearl Sword to touch.[7][9][lower-alpha 2][10] Before 1641, the monarch would take the sword for the duration of their visit, but in 1641 Charles I was offered it and immediately returned it to the Lord Mayor, a practice that was then carried on.[11] The ceremony as a whole dates back to 1215 and the Royal Charter allowing direct election of the mayor (now the Lord Mayor).[12] A similar ceremonial surrendering of the local Sword of State (a sword granted by royal gift or authorised by royal charter) is performed on royal visits to certain other cities, including York.[13]

At the coronation of George III on 22 September 1761, the royal Sword of State was forgotten and instead Francis Hastings, 10th Earl of Huntingdon, carried the Lord Mayor's Pearl Sword for the ceremony.[14][15]

Queen Elizabeth II planned to hit Idi Amin over the head with the Pearl Sword if he attended her Silver Jubilee in 1977, according to Lord Mountbatten's diary at the time.[16][17][18] In 2012 the ceremonial surrender of the Pearl Sword was carried out during her Diamond Jubilee.[19] In 2016 the Pearl Sword was carried by Lord Mayor Jeffrey Mountevans to lead the Queen into St Paul's Cathedral for a service in honour of her official 90th birthday.[20]

State Sword

The State Sword forms one half of the Sword and Mace, symbols of the authority of the Lord Mayor and the City of London Corporation. At ceremonial events it is carried by the Sword Bearer, while the mace is carried by the Serjeant-at-Arms. The City of London has had a Sword of State since before 1373 and the first known sword-bearer of the City was John Blytone, who resigned in 1395.[21] The current sword, which is from the mid 17th century, has a red velvet sheath and a pommel decorated with images representing Justice and Fame.[7] It is also called the Sunday Sword, and is one of a group of 8 swords made around the same time, between 1669 and 1684, and to similar specifications. Of these it particularly resembles the State Swords of Shrewsbury and Appleby-in-Westmorland. It was made around 1670 and acquired by London around 1680.[22]

The blade is 3 ft 1 1⁄2 in (0.953 m) long and 1 5⁄8 in (4.1 cm) wide. The hilt is 12 3⁄4 in (32 cm) long and it weighs 5 lb 1 1⁄4 oz (2.30 kg) without the scabbard. Most of the blue and gold damascene pattern that the blade used to have has since worn off.[5]

Lord Mayor Micajah Perry was attended by the "Sunday Sword and Mace" when he laid the foundation stone of Mansion House on 25 October 1739, where the City of London swords now form part of the plate collection.[7][23][lower-alpha 3] The Sword and Mace are also two of the symbols used when the new Lord Mayor is invested at the Lord Mayor's Show.[11]

Travelling State Sword

Because the State Sword is so valuable, there is in addition a Travelling State Sword used on ceremonial occasions outside the City of London. It looks very similar to the State Sword itself, but weighs less at 4 lb 0 oz (1.8 kg) and has a slightly longer blade at 3 ft 2 5⁄8 in (0.981 m). It was made by Wilkinson Sword in 1962 and presented to the City by Lord Mayor Sir Ralph Perring. Rather than the Damascene pattern, its blade is finely etched.[24]

Perring himself took the Travelling State Sword on its first foreign excursion, together with the mace, on a visit to Canada in 1963, during which he opened Ottawa's Exhibition.[25]

Old Bailey Sword

.jpg)

The Old Bailey Sword hangs behind the senior judge sitting at the Old Bailey, one of the buildings housing the Crown Court in London.[26] When the Lord Mayor opens the term at the Old Bailey, it is placed above his-or-her chair.[27] The Cutlers' Society records that this is the sword that was made by Richard Mathew in 1562–63 and presented to the City in 1563.[28] They quote William St John Hope describing it as follows:

"Its blade is of no great antiquity, but the pommel and quillons, which are of copper-gilt and handsomely wrought, belong to the sixteenth century, and very possibly to the sword given to the City by Richard Matthew, citizen and cutler, in 1563. The scabbard is covered with purple velvet and retains its original six lockets and chape of copper-gilt with intermediate devices of recent date."

— William St John Hope[28]

It has a blade 2 feet 11 3⁄4 inches (0.908 m) long and 1 5⁄8 in (4.1 cm) wide, and an 11 1⁄4 in (29 cm) hilt. It weighs 3 lb 6 3⁄4 oz (1.55 kg) without the scabbard. Five inches (13 cm) of the point have been damaged and repaired with electroplating. Like the Pearl Sword, the lower part of the blade is blued and decorated. Its scabbard is covered with crimson velvet and decorated with gold lace, copper-gilt and silver-gilt.[29]

Mansion House Justice Room Sword

The Justice Room of Mansion House was converted from the former Swordbearer's room in 1849 to operate as a court, since the Lord Mayor is chief magistrate of the City.[30] Though the court has since moved, the Mansion House Justice Room Sword retains the name.

Its blade is 2 ft 9 5⁄8 in (85.4 cm) long and 1 1⁄2 in (3.8 cm) wide. It has an 11 3⁄4 in (30 cm) hilt and weighs 4 lb 13 oz (2.2 kg) without the scabbard. It is from around 1830 and believed to be Portuguese.[31]

Related collections

Where the City of London has six ceremonial swords (including the Travelling Sword of State), Bristol, Lincoln and Exeter each have four, though two of Exeter's are not borne before the mayor. A further 13 places in Britain have two swords each, as does Dublin.[32]

The swords of the Lord Mayor of Bristol are:

- A Mourning Sword from before 1373 when Bristol became a county corporate, originally used as a Sword of State[33][34]

- A Pearl Sword from the 14th century given by Lord Mayor of London John de Welles[lower-alpha 4] in 1431.[32][35] Ewart Oakeshott described the Type XVII sword as being large and "of superlative quality" with a "beautiful silver gilt hilt".[36]

- A Lent Sword from the 15th century,[lower-alpha 5] formerly carried at the Lent assizes[34]

- A State Sword from 1752 described by Barrett (2017) as "an inelegant but grandiose giant of a sword with a blade almost twice as wide as any other mentioned."[37]

Lincoln's four are a Sword of State from before 1367, a Mourning, or Lent, Sword circa 1486, the Charles I sword, circa 1642, which is missing its hilt, and the George II Sword, put together in 1902 from a hilt made in 1734 and an older blade.[38] Exeter's bearing-swords are a Sword of State, circa 1497, and a Mourning Sword, circa 1577.[39]

Notes

- Wheatley quotes Hope as saying 1570 but Mason specifies 23 January 1571.[4][40]

- As described in The New York Times, 15 May 1887: "At the Queen's approach, the Lord Mayor received the pearl sword from the sword bearer. His Worship lowered the point, congratulated her Majesty in coming to the most loyal city, and presented the sword to the Queen. She took it and returned it."

- "I afterwards put on the Scarlet Gown and went to Stocks Market ... preceded by the City Musick and my Officers, with the Sunday Sword and Mace, and laid the chief corner stone of the said Mansion House". Perks, 1922, p. 183

- Variously spelled "de Wells" (Oakeshott), "de Welles" (Evans), "Wells" (Barrett), "Wallis" (inscription on the hilt, per Evans).

- Bristol County Council says circa 1459, Barrett (2017) says circa 1499.

References

- Marsden, Sam (17 April 2013). "Mourning sword in Thatcher ceremony was last used at Churchill's funeral". The Daily Telegraph. Retrieved 19 January 2018.

- Pepys 1893, p. 11.

- ""Thursday, May 28th, 1891"". Proceedings of the Society of Antiquaries of London. 2. XIII: 343. 1891.

- Pepys 1893, p.11 fn.1.

- Barrett 2017, p. 126.

- Cassell 1865, p. 403.

- "The Plate Collection". www.cityoflondon.gov.uk. City of London. Retrieved 19 January 2018.

- Barrett 2017, pp. 120–122.

- "The Queen in London. Her Majesty Formally Opens The People's Palace" (PDF). The New York Times. 15 May 1887. Retrieved 19 January 2018.

- Barrett 2017, p. 63.

- Hibbert 2011, pp. 144–145.

- Davies, Caroline (5 June 2002). "Pearl Sword opens City to sovereign". The Daily Telegraph. Retrieved 19 January 2018.

- Barrett 2017, pp. 61–63.

- Black, Jeremy (1 October 2008). George III: America's Last King. Yale University Press. p. 48. ISBN 978-0-300-14238-9.

- "The British Sword of State - A Wonderful Sabre of Immense Value". The Buffalo Commercial. 15 February 1900. p. 5. Retrieved 12 February 2018.

- Furness, Hannah (27 December 2013). "The Queen's plot to bash Idi Amin over the head with a pearl sword". The Daily Telegraph. Retrieved 19 January 2018.

- Withnall, Adam (28 December 2013). "The Queen 'plotted to hit Idi Amin with a sword' if he visited Britain". The Independent. Retrieved 19 January 2018.

- "The Queen 'Plotted To Hit Ugandan Dictator Idi Amin With Ceremonial Sword'". The Huffington Post. 28 December 2013. Retrieved 19 January 2018.

- "Treasures of London – The Pearl Sword". Exploring London. 9 August 2013. Retrieved 19 January 2018.

- Davies, Caroline (10 June 2016). "Queen's 90th birthday: Attenborough and Welby speak at St Paul's service". The Guardian. Retrieved 19 January 2017.

- Barrett 2017, p. 119.

- Barrett 2017, pp. 85–86.

- Perks 1922, pp. 182–183.

- Barrett 2017, pp. 131–133.

- Thomson, Ernest Chisolm (22 August 1963). "Lord Mayor Bringing Sword". The Ottawa Journal. Retrieved 12 February 2018.

- Peter; Mark (28 October 2014). Unseen London. Frances Lincoln. p. 107. ISBN 978-1-78101-187-4.

- Barrett 2017, p. 122.

- Welch 1916, pp. 222–223.

- Barrett 2017, pp. 122–123.

- Hibbert 2011, pp. 526.

- Barrett 2017, p. 129.

- Barrett 2017, p. 57.

- Barrett 2017, p. 51.

- "The history of the Lord Mayor". bristol.gov.uk. Bristol County Council. Retrieved 19 January 2017.

- Evans 1824, p. 101.

- Oakeshott 1964, p. 67.

- Barrett 2017, p. 58.

- Barrett 2017, pp. 149–155.

- Barrett 2017, pp. 213–217.

- Mason 1920, p. 11.

Works cited

- Barrett, Edward (2017). Ceremonial Swords of Britain: State and Civic Swords. The History Press. ISBN 978-0-7509-6244-5.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Cassell, John (1865). Cassell's Illustrated History of England. 5. Cassell, Petter and Galpin.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Evans, John (1824). A Chronological Outline of the History of Bristol, and the Stranger's Guide Through Its Streets and Neighbourhood. Bristol: John Evans.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Hibbert, Christopher; Weinreb, Ben; Keay, John; Keay, Julia (9 September 2011). The London Encyclopaedia (3rd Edition) (3rd ed.). Pan Macmillan. ISBN 978-0-230-73878-2.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Mason, A. E. W. (1920). The Royal Exchange: a note on the occasion of the bicentenary of the Royal Exchange Assurance. London: Royal Exchange.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Oakeshott, Ewart (1964). The Sword in the Age of Chivalry. Boydell Press. ISBN 978-0-85115-715-3.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Pepys, Samuel (1893) [1663]. Henry Benjamin Wheatley (ed.). The Diary of Samuel Pepys: For the First Time Fully Transcribed from the Shorthand Manuscript in the Pepysian Library. VI: July 6, 1663–Dec. 31, 1663. George E. Croscup.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Perks, Sidney, City Surveyor to the City of London (1922). "IX: The Building of the Mansion House". The History of the Mansion House. Cambridge University Press.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Welch, Charles (1916). History of the Cutlers' Company of London (PDF). London: The Cutlers' Company.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)