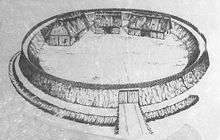

Circular rampart of Burg

The circular rampart of Burg (German: Ringwall von Burg) is a defensive work from the Early Middle Ages period located near the German town of Celle in Lower Saxony. The site, dating roughly to the 10th century and located in an inaccessible area of marsh by the River Fuhse, probably acted as a refuge for the local population. Today this 3-metre-high (9.8 ft) circular embankment belongs to one of the most important Early Middle Age historical monuments in Celle.

Location

The circular rampart at Burg is located in the Celle suburb of Altencelle, several hundred metres west of the settlement of Burg. It is easily accessed via an improved road and a field track. Formerly this defensive work lay on a sand dune in the middle of the wide, flat valley of the Fuhse. At that time the river ran northwards past the Burg, because another rampart was built to the south of the circular rampart with ditches in front of it. Today the river flows southwards past the site.

Description

In spite of the surrounding land being cultivated in past centuries the almost perfectly circular rampart, 70 to 85 metres in diameter whose interior covers about 0.2 hectares (0.49 acres), is well preserved. It still retains its original height of 3 metres. The rampart was made of plaggen, turves cut from peat bogs. In front of it to the south, facing the direction of attack, is a dry V-shaped ditch (Spitzgraben), 2 m deep and 6 m wide. Between the rampart and the ditch is a 5-metre-wide (16 ft) berm. The ditch was crossed by an earth bridge that led to the only entrance on the eastern side of the rampart. This is still visible today as a break in the embankment. To the north protection was afforded by the River Fuhse which, at that time, was about 50 m from the position.

A flight of stone steps has been built for visitors today leading to the top of the rampart. Stones have also been laid at the foot of the rampart in recent times. In front of the rampart is an information tablet with an explanation of the historical significance of the site.

Excavations

The first archaeological investigation was undertaken in 1906 by the archaeologist, Carl Schuchhardt, who cut through the embankment profile. This confirmed that the embankment had been built purely from plaggen, no remains of old wooden reinforcements being found.

A second dig took place between 1935 and 1936 carried out by the historian, Ernst Sprockhoff. He cleared a good third of the interior of the rampart.

This revealed post sockets which suggest that there were three buildings inside the site immediately next to the embankment. They would appear to be a 20 x 7 m hall, a secondary building and a barn. The entrance in the rampart was discovered, comprising an entrance passageway with wooden posts on either side and measuring 3 x 5 m. Finds included individual shards of pottery, a rusted knife and several horseshoes. These dated the defensive position to the 10th century. The find indicated only a short period of settlement. Sites of similar construction were not uncommon on the plains and appeared from the 8th to the 12th century as refuges for the population. During the excavation stone age flints and fireplaces were also discovered. They indicated that the sand dune in the valley of the Fuhse had already been settled in the Stone Age.

Adaptation

This well-preserved circular rampart gained renewed fame in the early 20th century, thanks to the novel Der Wehrwolf (The Werewolf) by Hermann Löns. Löns was inspired by the rampart site and set parts of his work at this location during the Thirty Years War. According to the novel, marauders and other warring groups passed through the land and plundered the farms of the heath farmers. The farming folk retreated to the old refuge. According to Löns' novel they fortified the site and built houses within its interior. One day they defended themselves successfully against an attack by Swedish Landsknechts ( pikemen with supporting infantry).

See also

References

- Ralf Busch: Die Burg in Altencelle: ihre Ausgrabung und das historische Umfeld, Celle, 1990, ISBN 3-925902-10-4