Church of St John the Baptist, Glastonbury

Described as "one of the most ambitious parish churches in Somerset",[1] the present Church of St John the Baptist in Glastonbury, Somerset, England, dates from the 15th century and has been designated as a Grade I listed building.[2]

| Church of St John the Baptist | |

|---|---|

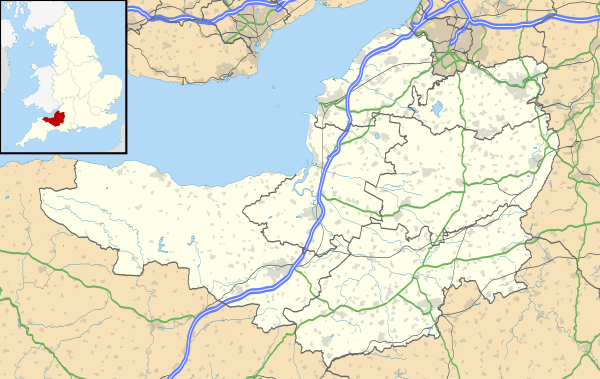

Location within Somerset | |

| General information | |

| Town or city | Glastonbury |

| Country | England |

| Coordinates | 51.1482°N 2.7162°W |

| Completed | 15th century |

History

The present church replaced an earlier one. Though documentary evidence for St John's survives only from the later 12th century, other evidence tends to suggest that a church existed on this site at a significantly earlier date.[3] According to legend, the original church was built by Saint Dunstan in the tenth century.[4] Recent excavations in the nave have revealed the foundations of a large central tower that possibly dated from Saxon times, and a later Norman nave arcade on the same plan as the existing one. A central tower survived until the 15th century, but is believed to have collapsed, at which time the church was rebuilt.[5] In the north aisle, 12th-century fabric survives in the former Saint Katherine's Chapel.[6]

The church was used for shelter by Monmouth's troops in June 1685 during the Monmouth Rebellion.[7] It is also recorded that on four occasions between 1800 and 1804, French prisoners of war were locked up for the night inside the church, presumably whilst in transit.[8]

Between 1856-57 the church was restored and reseated by Sir George Gilbert Scott at a cost of £3000, and its gothic character re-emphasized.[5] The church conforms in its entirety to a style of architecture known as Perpendicular Gothic.

The church is built of Doulting stone, Street stone and the local Tor burr,[5] and is laid out in a cruciform plan with an aisled nave and a clerestory of seven bays.

Interior

The interior of the church includes four 15th-century tomb-chests, some 15th-century stained glass in the chancel, medieval vestments, and a domestic cupboard of about 1500 which was once at Witham Charterhouse.[9]

At the front of the tower are two large carvings, the 'Madonna with Child' and the 'Resurrection Christ' – early works of Ernst Blensdorf, carved in 1945, after his escape from the Nazis.[8]

Tower and Bells

The west tower has elaborate buttressing, panelling and battlements. The tower rises to a height of 134½ feet (about 41 metres), and is the second tallest parish church tower in Somerset.[5] During the 15th century the present tower at the western end of the church replaced an earlier central tower.[10] The tower is said to have inspired numerous others, including the tower of Northington Parish Church in Hampshire.[11] The tower is unusual in that it has a chiming clock, but no clock face.[5]

There has been a set of bells at St John's Church since 1403. The oldest existing bell was originally made in 1612 and inscribed 'I sound to bid the sick repent in hope of life when breath is spent'. This bell was recast in 1992. The ring of six bells was augmented to a ring of eight in 1878[12] The largest, the tenor bell, is about 14 cwt or about 712 kg and the smallest, the treble, is about 5 cwt or 250 kg.[5]

Churchyard

In the churchyard is a thorn tree grown from a cutting from the Glastonbury Thorn. A blossom from this tree is sent to the Queen every Christmas.[13] At the end of term, the pupils of St John's Infants School gather round the tree in St John's parish churchyard on the High Street. They sing carols, including one specially written for the occasion, and the oldest pupil has the privilege of cutting the branch of the Glastonbury Thorn that is then taken to London and presented to Her Majesty The Queen.

The tercentennial labyrinth, located close to the church gates, was laid in 2007, to celebrate Glastonbury receiving its town charter from Queen Anne in 1705. This is a grass labyrinth of the classical seven circuit design, its path delineated by blue lias stonework, which is a local stone present in the Tor. The labyrinth was conceptualized and designed by Sig Lonegren (a Glastonbury geomancer and author). The laying of the labyrinth was delayed due to various problems in securing a site.[14]

List of Vicars

- Richard Prat, BA 1744 - 1778[15]

- Matthew Hodge 1783 - 1808[16]

- John Townsend, MA 1809 - 1812[17]

- Thomas Parfitt, DD 1812 - 1865[18]

- Charles Sydenham Ross, MA 1865 - 1893[19][20]

- Prebendary Henry Lowry Barnwell, MA 1894 - 1912[21]

- Charles Victor Parkinson Day, MA, CBE, TD 1912 - 1921[22]

- Lionel Smithett Lewis, MA 1921 - 1950[23]

- Prebendary Bernard F Cooper, BD 1950[24]

- Hugh William Hartly Knapman, BA, RD 1955 [25][26]

- Alan Geoffrey Clarkson, MA 1974 [27]

- Patrick John Riley 1984 - 2001[26]

- Maxine Marsh 2002 - 2007 (Priest-in-Charge)[28]

- David MacGeoch, RD 2008–Present

Thomas Parfitt has been the longest serving vicar of Glastonbury, having held the office for more than 52 years, between December 1812 and his death, aged 88 years, in January 1865. Dr Parfitt was also vicar of St Benedict's Church, Glastonbury, until this became a separate cure in 1845.[29]

Charles Sydenham Ross was a curate at Glastonbury for seven years, until succeeding Dr Thomas Parfitt as vicar in 1865. Mr Ross was noted as having been "of Scotch extraction, born at sea off the coast of Portugal". He died during a service at Glastonbury Parish Church on Christmas Eve, 1893 and a local newspaper remarked, "The manner of his death was beautifully touching, for he sank quietly to rest as his congregation were singing the Nunc Dimittis". Mr Ross had been unwell for many months and the bulk of the work in the parish had been carried out by the Reverend H.L Barnwell, who was to succeed him.[30]

Henry Lowry Barnwell was licensed as a curate to Saint John's in 1889.[31] He served as vicar for 18 years, until his death in 1912 and in the following year, a beautifully designed oak screen was erected to his memory in the side chapel.[32]

Charles Victor Parkinson Day volunteered for service soon after the outbreak of World War One, as a chaplain to the forces, his rank being equal to that of colonel. Consequently, although he was Vicar of Glastonbury for nine years, more than half of this time was spent in France, Mesopotamia and other war areas. The Reverend Herbert Davies took charge of the parish during his absence. Mr Day remained with the troops for the duration of the war and was appointed a CBE. He died suddenly at Clifton in 1921.[33]

Lionel Smithett Lewis was a prominent member of the Church Anti-vivisection League (founded in 1889) and also a founder of Blue Cross, which campaigned against the inhumane treatment of horses at the front during the First World War. Following his appointment as Vicar of Glastonbury in 1921, he developed a passionate interest in the Holy Grail and the legends of Joseph of Arimathea and became a well-known author on the subject.[34]

Mr Lewis was succeeded by Bernard F Cooper, who had been vicar of Bathwick and Rural Dean of Bath[35] and then by Hugh William Hartly Knapman, who had been vicar of Long Ashton since 1938.[25]

Alan Clarkson later became Archdeacon of Winchester.[36]

Current Ministry and Profile

The current vicar of Saint John's, Glastonbury is the Reverend David MacGeoch, assisted by the Reverend Sister Diana Greenfield, the Reverend Robin Ray and a team of lay readers. It is linked with the parishes of St Benedict's Church in Glastonbury and St Mary's & All Saints Church in the village of Meare as a joint benefice.[37]

Music

The church has a strong musical tradition and close ties with the nearby Cathedral of Wells. A surpliced choir and processions at St John's was first introduced by Charles Sydenham Ross, incumbent from 1865.[3] Today, St John's choir is made up of a large group of adults and juniors under the direction of Matthew Redman, organist and choirmaster. The choir is of such a standard that it sings regularly in the cathedrals of Exeter, Salisbury, Hereford and Wells. With the help of the Cathedral School in Wells and the Wells Cathedral organist, Saint John's Glastonbury has been able to develop a scholarship, whereby each year an organ scholar is appointed to work with the Director of Music to gain experience of working within a parish church.[38]

See also

- List of Grade I listed buildings in Mendip

- List of towers in Somerset

- List of ecclesiastical parishes in the Diocese of Bath and Wells

References

- http://www.britishlistedbuildings.co.uk/en-265926-church-of-st-john-the-baptist-glastonbur#.Vg7skWYtC1s

- "Church of St John the Baptist, High Street (North side), Glastonbury". Somerset Historic Environment Record. Somerset County Council. Retrieved 2009-05-18.

- http://www.british-history.ac.uk/vch/som/vol9/pp16-43#h3-0020

- Brooks, Nicholas: "Anglo-Saxon Myths: State and Church, 400 - 1066", Hambledon Press, 2000

- http://www.stjohns-glastonbury.org.uk (official church website)

- "Great Britain: The Green Guide", By Michelin Travel & Lifestyle, 2012

- Dunning, Robert (1996). Fifty Somerset Churches. Somerset Books. pp. 121–124. ISBN 978-0861833092.

- Boyd, Martin: "St John the Baptist, Glastonbury" (Church Guide)

- Historic England. "Church of St John the Baptist (1345459)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 2009-05-18.

- "Church of St John and churchyard, Glastonbury". Somerset Historic Environment Record. Somerset County Council. Retrieved 29 December 2015.

- Brian l Harris: "Guide to Churches and Cathedrals", Ebury Press, 2006.

- A History of the County of Somerset: Volume 9, Glastonbury and Street. Originally published by Victoria County History, London, 2006.

- Humphrys, Geoffrey (December 1998). "Attempts to regrow the Glastonbury thorn after it died in 1991". History Today. Retrieved 2009-03-19.

- https://druidnetwork.org/what-is-druidry/beliefs-and-definitions/sacred-places/glastonburys-tercentennial-labyrinth/

- http://www.butleigh.org/butleighpeople/ButleighPeopleP.html

- Clergy of the Church of England Database, Person ID 43377

- Foster, Joseph: Alumni Oxonienses, Vol IV (1715-1886), p 1431

- Obituary - Gentleman's Magazine, and Historical Chronicle, Volume 79 (1865)

- London Evening Standard, 29.12.1893

- The Guardian, Obituary, 03.01.1894

- Venn, John: Alumni Cantabrigienses

- The Durham University Journal, Volume 22, Page 371

- Venn, John: Alumni Cantabrigienses, 1951

- Bath Chronicle and Weekly Gazette, 14 October 1950

- Crockford's Clerical Directory, Issue 81, 1965

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2013-08-20. Retrieved 2016-01-29.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- Crockford's Clerical Directory, Issue 90, 1987, p.108

- Church Times, Obituary 05.07.2013

- Bristol Times and Mirror, 16 January 1865

- The Bristol Mercury, 29 December 1893

- Western Daily Press, 14 November 1889

- Wels Journal, 13 June 1913

- Wells Journal, 26 August 1921

- http://www.stgite.org.uk/stmarkwhitechapel.html

- Bath Chronicle and Weekly Gazette, 14 October 1950,

- The Independent, 04.01.1999: Church resignations and retirements.

- "St John the Baptist Church, Glastonbury". A Church Near You. Church of England. Retrieved 28 December 2015.

- "St John's Choir, Glastonbury to sing Evensong". Line Up. Retrieved 23 August 2017.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to St John the Baptist's, Glastonbury. |