Christianity in Eastern Arabia

Christians reached the shores of the Persian Gulf by the beginning of the fourth century. According to the Chronicle of Seert,[1] Bishop David of Perat d'Maishan was present at the Council of Seleucia-Ctesiphon, around 325, and sailed as far as India. Gregory Bar Hebraeus, Chron. Eccles, 2.10 (v. 3, col. 28) indicates that David had earlier ordained one of the other bishops present at the Council. The monk Jonah is said to have established a monastery in the Persian Gulf "on the shores of the black island" in the middle of the fourth century.[2] A Nestorian bishopric was established at Rev Ardashir, nearly opposite the island of Kharg, in Southern Persia, before the Council of Dadisho in AD 424.

Eastern Arabia was divided into two main ecclesiastical regions: Beth Qatraye (northeastern Arabia) and Beth Mazunaye (southeastern Arabia). Christianity in Eastern Arabia was blunted by the arrival of Islam by 628.[3] Despite this, the practice of Christianity persisted in the region until the late 9th century.[4]

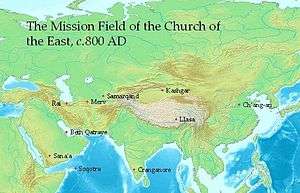

From the fifth century onward the Persian Gulf fell under the jurisdiction of the Church of the East. Christian sites have been discovered dating from that time until after the advent of Islam in the region at Failaka, Kharg, Jubail and the nearby settlements of Thaj, al-Hinnah and Jabal Berri, and Sir Bani Yas.

History

After the region fell under the reign of the Sasanian Empire in the early third century, many of the inhabitants in Eastern Arabia were introduced to Christianity following the eastward dispersal of the religion by Mesopotamian Christians.[5] However, it was not until the fourth century that Christianity gained popularity in the region.[6] This was, in large part, due to the arrival of Christians who faced persecution in Iraq and Iran under the reign of Shapur II starting in 339. Another factor in the growing influence of Christianity was the migration of Christian traders to the region who were looking to capitalize on the well-established pearl trade.[7]

A sizable Christian presence in Eastern Arabia soon emerged thereafter. The monk Jonah alludes to the presence of a monastery on the Black Islands, in the southern portion of Beth Qatraye, built between 343 and 346 by a monk named Mar Zadoe.[8][9] Furthermore, the Chronicle of Seert mentions a monk named 'Abdisho who Christianized the locals of Ramath, an island located between Kuwait and Qatar, and built a monastery there sometime between 363 and 371.[8] Nestorian records attest to a consistent Christian presence in the region between the fifth and seventh centuries, as evidenced by the regular attendance of synods by local bishops.[8]

The Christian population consisted mainly of Syriac and Persian speakers, while the remainder consisted primarily of Arabic-speakers deriving from the Abd al-Qays tribe.[8] Communities often competed over the construction of churches and parishes. In addition to facilitating the celebration of festive occasions, monasteries were also famous for their vineyards and were often visited for wine tasting.[10] Churches also typically provided basic services such as schooling and healthcare.[11]

According to Islamic tradition, in 628, Muhammad sent a Muslim envoy named Al-Ala'a Al-Hadrami to Munzir ibn Sawa, a ruler in Eastern Arabia, requesting that he and his people accept Islam.[3][12] Most of the Pagan practitioners converted to Islam shortly thereafter.[13] However, the monotheistic population, who consisted of Jews and Zoroastrians in addition to Christians, did not instantaneously convert. Instead, they chose to pay the jizya, a tax for non-Muslims.[6]

Christianity abated in the region sometime around the ninth century.[14]

Historical regions

Beth Qatraye

The Christian name used for the region encompassing north-eastern Arabia was Beth Qatraye, or sometimes also called "the Isles".[15] The name translates to "region of the Qataris" in Syriac.[16] It included the present-day areas of Bahrain, Tarout Island, Al-Khatt, Al-Hasa, and Qatar.[14] Some parts of the United Arab Emirates may also have been included.[14] The region contained monasteries from the fourth to ninth century.[14] From the sixth to seventh century, bishops were known to be stationed in the districts of Mashmahig (Samaheej), Dayrin (Tarout Island), Mazun, Hagar, and Ḥaṭṭa.[17] The bishops of Beth Qatraye stopped attending synods in 676; although Christianity persisted in the region until the late 9th century.[4]

By the 5th century, Beth Qatraye was a major centre for Church of the East Nestorian Christianity, which had come to dominate the southern shores of the Persian Gulf.[4][18] As a sect, the Nestorians were often persecuted as heretics by the Byzantine Empire, but eastern Arabia was outside the Empire's control offering some safety.[4]

The dioceses of Beth Qatraye did not form an ecclesiastical province, except for a short period during the mid-to-late seventh century.[4] They were instead subject to the Metropolitan of Fars. In the late seventh century, Beth Qatraye rebelled against the authority of Fars. In an effort to reconcile the bishops of Qatraye, Giwargis I held a synod at Dayrin (Tarout Island) in 676.[19]

In the seventh and eighth centuries, an important literary culture emerged in Beth Qatraye. Several notable Nestorian writers originating from Beth Qatraye are ascribed to this period, including Isaac of Nineveh, Dadisho Qatraya, Gabriel of Qatar and Ahob of Qatar.[20] A number of archaeological sites are also dated to this time-frame.[14]

There is some ambiguity pertaining to the language used in Beth Qatraye.[21] Written text contained both Persian and Semitic words. While some of the Semitic words are Arabic, the general morphology and phonetics bear more resemblance to Aramaic.[22][23] German orientalist Anton Schall categorized the language as 'Southeastern Aramaic'.[22][24] Because of this unique fusion of linguistic elements, the monks of Beth Qatraye were active in translating texts between Persian, Syriac and Arabic. It is said that a Christian from Beth Qatraye even served as the official Persian translator for King al-Nu'man III ibn al-Mundhir who was a native Arabic speaker.[17]

Archaeology

Akkaz

In 1993 a joint Kuwaiti-French expedition found a church in Akkaz (in present Kuwait) dating to the early Abbasid era. The church was in the eastern church style and is symmetrical to that of Failaka.[25][26]

Failaka

Remnants of a church, dating to perhaps as early as the 5th or 6th century as determined by the crosses that form part of the stucco decoration, were found at Al-Qusur on the Kuwaiti island of Failaka. Pottery at the site can be dated from as early as the first half of the 7th century through the 9th century.[27][28]

Kharg

A number of tombs have been found decorated with distinctive Nestorian crosses on Kharg Island. A monastery with a church and nearby homes for married priests have also been excavated. The floral designs in the plaster decoration of the church suggested to the excavator a date in the fifth or sixth centuries AD.[29] Later studies would seem to date the decorations to the end of the sixth century AD.[30]

Jubail and nearby areas

A church consisting of a walled courtyard and three rooms on the east side was found in 1986 in Jubail. Cross designs were seen to have been impressed into the plaster flanking the doors of the structure. The reporter of the site did not indicate a clear date for it, but suggested that it must have been in existence for two centuries before the advent of Islam. Christian gravestones were also found at the site. At Thaj, 90 km to the west, what appears to be a smaller church or chapel, built of reused stones and perhaps dating to the fifth or sixth century, has been discovered. 10 km NE of Thaj, at al-Hinnah, there is evidence of a Christian cemetery of ancient but unknown date.[31] A church was identified in the island of Abu 'Ali near Jubail.[32]

Jabal Berri

Not far to the South of Jubail, at Jabal Berri, three bronze crosses have been found dating possibly to the period when Sassanian Persia had influence over the region.[33] Ruins of a nearby settlement suggests that a Christian community may have resided in the area.[34]

Muharraq

Old foundations of a Nestorian monastery were discovered in Samaheej, a village in Muharraq, Bahrain. Another village in Muharraq, known as Al Dair, may have facilitated a monastery, as its name translates 'cloister' or 'monastery' in Aramaic.[35]

Qasr Al Malehat

A site on the south-east coast of Qatar, near Al Wakrah, revealed the remnants of a structure purported to be a church. It was built directly on limestone bedrock and a hearth was found inside the ruins. Radiocarbon dating indicates the site was occupied in the early 7th century, and potsherds recovered from the surrounding area evidences continued occupation until the mid to late 8th century. The ceramics are consistent with those found in other Nestorian sites in the Eastern Arabia and the structure bears resemblance to the excavated church in Jubail.[36]

Umm Al Maradim

An excavation carried out in 2013 uncovered a Nestorian cross in Umm Al Maradim, a site in central Qatar. The cross is made of hard stone and measures between 3 and 4 cm. A number of hearths and potsherds were found at the site, though no structures were discovered.[37]

Sir Bani Yas

At Sir Bani Yas, an island off the Western coast of the United Arab Emirates, an extensive monastic and ecclesiastical complex has been found similar to that at Kharg. It is considered one of the most extensive monasteries in Eastern Arabia.[14] Excavations took place between 1993 and 1996.[14] The church building itself was about 14 m × 4.5 m. As with other sites in the region, plaster crosses were excavated. The excavator suggests a date in the sixth or seventh century for the construction of the church.[38]

See also

References

- pp. 236 & 292.

- Peter Hellyer, "Nestorian Christianity in Pre-Islamic UAE and Southeastern Arabia", Journal of Social Affairs 18.72 (2001), 79–92, and original text referenced in Bibliotheca Hagiographica Orientalis, 527–530.

- Fromherz, Allen (13 April 2012). Qatar: A Modern History. Georgetown University Press. p. 43. ISBN 978-1-58901-910-2.

- "Christianity in the Gulf during the first centuries of Islam" (PDF). Oxford Brookes University. Archived from the original (PDF) on 28 May 2015. Retrieved 27 May 2015.

- Gillman, Ian; Klimkeit, Hans-Joachim (1999). Christians in Asia Before 1500. University of Michigan Press. p. 87. ISBN 978-0472110407.

- Kozah, Abu-Husayn, Abdulrahim, Al-Thani. p. 54–55.

- Kozah, Abu-Husayn, Abdulrahim, Al-Thani. p. 56.

- Kozah, Abu-Husayn, Abdulrahim, Al-Thani. p. 57.

- Vööbus, Arthur (1958). History of Asceticism in the Syrian Orient. Peeters. pp. 308–309. ISBN 978-9042902183.

- Kozah, Abu-Husayn, Abdulrahim, Al-Thani. p. 256.

- Kozah, Abu-Husayn, Abdulrahim, Al-Thani. p. 257.

- Poonawala, Ismail K. (1990). The History of al-Tabari Vol. 9: The Last Years of the Prophet: The Formation of the State A.D. 630-632/A.H. 8-11. p. 95. ISBN 978-0887066924.

- Kozah, Abu-Husayn, Abdulrahim, Al-Thani. p. 250.

- Kozah, Mario; Abu-Husayn, Abdulrahim; Al-Murikhi, Saif Shaheen; Al-Thani, Haya (2014). The Syriac Writers of Qatar in the Seventh Century (print ed.). Gorgias Press LLC. p. 24. ISBN 978-1463203559.

- "Nestorian Christianity in the Pre-Islamic UAE and Southeastern Arabia", Peter Hellyer, Journal of Social Affairs, volume 18, number 72, winter 2011, p. 88

- "AUB academics awarded $850,000 grant for project on the Syriac writers of Qatar in the 7th century AD" (PDF). American University of Beirut. 31 May 2011. Archived from the original (PDF) on 28 May 2015. Retrieved 12 May 2015.

- "Beth Qaṭraye". Gorgias Encyclopedic Dictionary of the Syriac Heritage: Electronic Edition. Retrieved 26 January 2019.

- Curtis E. Larsen. Life and Land Use on the Bahrain Islands: The Geoarchaeology of an Ancient Society University Of Chicago Press, 1984.

- Kozah, Abu-Husayn, Al-Murikhi, Al-Thani. p. 7.

- Kozah, Abu-Husayn, Abdulrahim, Al-Thani. p. 1.

- Kozah, Abu-Husayn, Abdulrahim, Al-Thani. p. 151.

- Kozah, Abu-Husayn, Abdulrahim, Al-Thani. p. 152.

- Contini, Riccardo (2003). La lingua del Bét Qaträyë.

- Schall, Anton (1989). Der nestorianische Bibelexeget lsödäd von Merw. Wiesbaden: Otto Harrassowitz.

- Ioannou Y., Métral F., Yon M., (dir.), Chypre et la Méditerranée orientale : formations identitaires, perspectives historiques et enjeux contemporains, Actes du colloque tenu à Lyon, Université Lumière-Lyon 2, Université de Chypre, TMO 31, Lyon, Maison de l'Orient méditerranéen, 1997.

- Calvet, 674.

- Vincent Bernard and Jean Francois Salles, "Discovery of a Christian Church at Al-Qusur, Failaka (Kuwait)," Proceedings of the Seminar for Arabian Studies 21 (1991), 7–21. Vincent Bernard, Olivier Callot and Jean Francois Salles, "L'eglise d'al-Qousour Failaka, Etat de Koweit," Arabian Archaeology and Epigraphy 2 (1991): 145-181.

- Yves Calvet, "Monuments paléo-chrétiens à Koweit et dans la région du Golfe," Symposium Syriacum, Uppsala University, Department of Asian and African Languages, 11-14 August 1996, Orientalia Christiana Analecta 256 (Rome, 1998), 671–673.

- R. Ghirshman, The Island of Kharg, 2nd edition (Tehran: Iranian Oil Operating Companies, 3rd printing, 1965).

- Marie-Joseph Steve, L'Île de Kharg, Civilisations du Proche-Orient 1 (Neuchatel: Recerches et Publications, 2003), 129–130.

- John A. Langfeldt, "Recently discovered early Christian monuments in Northeastern Arabia", Arabian Archaeology and Epigraphy 5 (1994), 32–60.

- D.T. Potts, The Arabian Gulf in Antiquity, Vol. II (1990), p. 245.

- D. T. Potts, "Nestorian Crosses from Jabal Berri", Arabian Archaeology and Epigraphy 5 (1994), 61–65.

- Kozah, Abu-Husayn, Abdulrahim, Al-Thani. p. 27.

- Kozah, Abu-Husayn, Abdulrahim, Al-Thani. pp. 28–29.

- Kozah, Abu-Husayn, Abdulrahim, Al-Thani. pp. 30–31.

- Kozah, Abu-Husayn, Abdulrahim, Al-Thani. pp. 29–30.

- G. R. D. King, "Nestorian monastic settlement on the island of Sir Bani Yas, Abu Dhabi: a preliminary report", Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies 60.2 (1997), 221–235.

External links

- Sir Bani Yas, Abu Dhabi Islands Archaeological Survey. Gives online access to several of the cited publications.