Ceiba

Ceiba is a genus of trees in the family Malvaceae, native to tropical and subtropical areas of the Americas (from Mexico and the Caribbean to N Argentina) and tropical West Africa.[2] Some species can grow to 70 m (230 ft) tall or more, with a straight, largely branchless trunk that culminates in a huge, spreading canopy, and buttress roots that can be taller than a grown person. The best-known, and most widely cultivated, species is Kapok, Ceiba pentandra, one of several trees called kapok.

| Ceiba | |

|---|---|

| |

| Ceiba pentandra leaves and fruit | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Plantae |

| Clade: | Tracheophytes |

| Clade: | Angiosperms |

| Clade: | Eudicots |

| Clade: | Rosids |

| Order: | Malvales |

| Family: | Malvaceae |

| Subfamily: | Bombacoideae |

| Genus: | Ceiba Mill.[1] |

| Species | |

|

18 species, see text | |

Ceiba species are used as food plants by the larvae of some Lepidoptera (butterfly and moth) species, including the leaf-miner Bucculatrix ceibae, which feeds exclusively on the genus.

Recent botanical opinion incorporates Chorisia within Ceiba and puts the genus as a whole within the family Malvaceae.[2]

Culture and history

The tree plays an important part in the mythologies of pre-Columbian Mesoamerican cultures. For example, several Amazonian tribes of eastern Peru believe deities live in Ceiba tree species throughout the jungle. The Ceiba, or ya’axché (in the Mopan Mayan language), symbolised to the Maya civilization an axis mundi which connects the planes of the Underworld (Xibalba) and the sky with that of the terrestrial realm. This concept of a central world tree is often depicted as a Ceiba trunk. The unmistakable thick conical thorns in clusters on the trunk were reproduced by the southern lowland Maya of the Classical Period on cylindrical ceramic burial urns or incense holders.

Modern Maya still often respectfully leave the tree standing when harvesting forest timber.[3] The Ceiba tree is represented by a cross and serves as an important architectural motif in the Temple of the Cross Complex at Palenque.[4]

Ceiba Tree Park is located in San Antón, Ponce, Puerto Rico. Its centerpiece is the historic Ceiba de Ponce, a 500-year-old Ceiba pentandra tree associated with the founding of the city.[5][6] In the surroundings of the legendary Ceiba de Ponce, broken pieces of indigenous pottery, shells, and stones were found to confirm the presence of Taino Indians long before the Spaniards that later settled in the area."[7] In 1525, Spanish Conquistador Hernán Cortés ordered the hanging of Aztec emperor Cuauhtemoc from a Ceiba tree after overtaking his empire. The town of Chiapa de Corzo, Chiapas, Mexico was founded in 1528 by the Spanish around La Pochota, Ceiba pentandra, according to tradition. Founded in 1838, the Puerto Rican town of Ceiba is also named after this tree. The Honduran city of La Ceiba founded in 1877 was named after a particular Ceiba tree that grew down by the old docks. In 1898, the Spanish Army in Cuba surrendered to the United States under a Ceiba, which was named the Santiago Surrender Tree, outside of Santiago de Cuba.

Ceiba is also the national tree of Guatemala. The most important Ceiba in Guatemala is known as La Ceiba de Palín Escuintla which is over 400 years old. In Caracas, Venezuela there is a 100-year-old ceiba tree in front of the San Francisco Church known as La Ceiba de San Francisco and is an important element in the history of the city. The towering specimen near the town of Sabalito, Costa Rica, is a relict tree called "la ceiba" by residents and a survivor of one of the highest terrestrial rates of tropical deforestation.[8]

Ceiba pentandra produces a light and strong fiber (kapok) used throughout history to fill mattresses, pillows, tapestries, and dolls. Kapok has recently been replaced in commercial use by synthetic fibers. The Ceiba tree seed is used to extract oils used to make soap and fertilizers. The Ceiba continues to be commercialized in Asia, especially in Java, Malaysia, Indonesia and the Philippines.

Ceiba pentandra is the central theme in the book titled, The Great Kapok Tree by Lynne Cherry. Ceiba insignis and Ceiba speciosa are added to some versions of the hallucinogenic drink Ayahuasca.

Pablo Antonio Cuadra, a Nicaraguan poet, wrote a chapter about the Ceiba tree. He used it as a symbol of the Nicaraguan ancestral roots, a cradle for the nation, and source during the people's exile.[9]

Species

- Ceiba aesculifolia (Kunth) Britten & Baker f.

- Ceiba boliviana Britten & Baker f.

- Ceiba chodatii (Hassl.) Ravenna

- Ceiba crispiflora (Kunth) Ravenna

- Ceiba erianthos (Cav.) K. Schum.

- Ceiba glaziovii (Kuntze) K. Schum.

- Ceiba insignis (Kunth) P. E. Gibbs & Semir

- Ceiba jasminodora (A. St.-Hil.) K. Schum.

- Ceiba lupuna P. E. Gibbs & Semir

- Ceiba pentandra (L.) Gaertn.

- Ceiba pubiflora (A. St.-Hil.) K. Schum.

- Ceiba rubriflora Carv.-Sobr. & L.P.Queiroz

- Ceiba samauma (Mart.) K. Schum.

- Ceiba schottii Britten & Baker f.

- Ceiba soluta (Donn. Sm.) Ravenna

- Ceiba speciosa (A. St.-Hil.) Ravenna

- Ceiba trischistandra (A. Gray) Bakh.

- Ceiba ventricosa (Nees & Mart.) Ravenna

Gallery

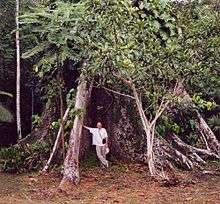

- Ceiba tree at O Parks, WildLife, and Recreation, El Ostional, Nicaragua

- Ceiba tree at O Parks, WildLife, and Recreation, El Ostional, Nicaragua

Ceiba pentandra found in the center plaza of Chiapa de Corzo, Chiapas, Mexico.

Ceiba pentandra found in the center plaza of Chiapa de Corzo, Chiapas, Mexico.- Ceiba pentandra in Lal Bagh gardens in Bangalore (Bengaluru), India

Flower of Palo Borracho, Cordoba, Argentina

Flower of Palo Borracho, Cordoba, Argentina Flower of Ceiba speciosa, Paineira rosa, São Paulo, Brazil

Flower of Ceiba speciosa, Paineira rosa, São Paulo, Brazil- Trunk of Ceiba speciosa (Paineira rosa), São Paulo, Brazil

Ceiba graviozii, (paineira branca), São Paulo, Brazil

Ceiba graviozii, (paineira branca), São Paulo, Brazil Paineira branca flower, São Paulo, Brazil

Paineira branca flower, São Paulo, Brazil Fruits, São Paulo, Brazil

Fruits, São Paulo, Brazil Fruits, São Paulo, Brazil

Fruits, São Paulo, Brazil Ceiba speciosa × C. insignis, a Huntington seedling flower, San Marino, California

Ceiba speciosa × C. insignis, a Huntington seedling flower, San Marino, California Ceiba speciosa in Lahore

Ceiba speciosa in Lahore Ceiba speciosa in Lahore

Ceiba speciosa in Lahore

References

- "Ceiba Mill". Germplasm Resources Information Network. United States Department of Agriculture. 2003-06-05. Archived from the original on 2009-05-07. Retrieved 2009-10-13.

- A TAXONOMIC REVISION OF THE GENUS CEIBA MILL.(2003)

- (BBC Earth News) "Sacred plants of the Maya forest", 5 June 2009 accessed 6 June 2009. Pachira aquatica and Pseudobombax ellipticum are also represented in the designs of similar ceramics.

- Houston, Stephen (1996) Symbolic Sweatbaths of the Maya: Architectural Meaning in the Cross Group at Palenque, Mexico. Latin American Antiquity, 7(2), pp. 132-151. Missing or empty

|title=(help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - En intensivo la venerada Ceiba de Ponce. Jason Rodríguez Grafal. La Perla del Sur. Ponce Puerto Rico. 19 July 2011. Retrieved 20 July 2011.

- Explore Puerto Rico By Harry S. Pariser. Page 246.

- Ceiba de Ponce. TravelPonce

- One Tree By Gretchen C. Daily and Charles J. Katz Jr.

- Cuadra, Pablo Antonio (Oct 23, 2007). Seven Trees Against the Dying Light: A Bilingual Edition. Northwestern University Press. pp. xi.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Ceiba. |