Charro

A charro is a traditional horseman from Mexico, originating in the central regions primarily in the states of Hidalgo, Nayarit, Jalisco, Colima, Michoacán, Zacatecas, Durango, Chihuahua, Aguascalientes, Querétaro, Guanajuato and Mexico State. The vaquero and ranchero (Spanish: "cowboy" and "rancher") are similar to the charro but different in culture, etiquette, mannerism, clothing, tradition and social status. The inhabitants of southern Salamanca are also called "charros" (feminine: "charra"). Among these, the inhabitants of the regions of Alba, Vitigudino, Ciudad Rodrigo and Ledesma are specifically known for their traditional "ganadería" heritage and colorful glitzy clothing.

Charreada has become the official sport of Mexico and maintains traditional rules and regulations in effect from colonial times up to the Mexican Revolution.[1]

Etymology

The word charro is first documented in Spain in the 17th century (1627) as a synonym of "person who stops" (basto), "person who speaks roughly" (tosco), "person of the land" (aldeano), "person with bad taste",[2] and attributes its origins to the Basque language from the word txar which means "bad", "weak", "small". The Real Academia maintains the same definition and origin.[3]

Origins

The Viceroyalty of New Spain had prohibited Native Americans from riding or owning horses, with the exception of the Tlaxcaltec nobility, other allied chieftains, and their descendants. However, cattle raising required the use of horses, for which farmers would hire cowboys who were preferably mestizo and, rarely, Indians. Some of the requirements for riding a horse were that one had to be employed by a plantation, had to use saddles that differed from those used by the military, and had to wear leather clothing from which the term "cuerudo" (leathered one) originated.

Over time landowners and their employees, starting with those living in the Mexican Plateau and later the rest of the country, adapted their cowboy style to better suit the Mexican terrain and temperature, evolving away from the Spanish style of cattle raising. After the Mexican War of Independence horse riding grew in popularity. Many riders of mixed race became mounted mercenaries, messengers and plantation workers. Originally known as Chinacos, these horsemen later became the modern "vaqueros". Wealthy plantation owners would often acquire decorated versions of the distinctive Charro clothing and horse harness to display their status in the community. Poorer riders would also equip their horses with harness made from agave or would border their saddles with chamois skin.

Mexican War of Independence and the 19th century

As the Mexican War of Independence began in 1810 and continued for the next 11 years, charros were very important soldiers on both sides of the war. Many haciendas, or Spanish owned estates, had a long tradition of gathering their best charros as a small militia for the estate to fend off bandits and marauders. When the War for Independence started, many haciendas had their own armies in an attempt to fend off early struggles for independence.[4]

After independence was achieved in 1821, political disorder made law and order hard to establish throughout much of Mexico. Large bands of bandits plagued the early 19th century as a result of lack of legitimate ways for social advance. One of the most notable gang was called "the silver ones" or the "plateados"; these thieves dressed as traditional wealthy charros, adorning their clothing and saddles with much silver, channeling the elite horseman image.[5] The bandit gangs would disobey or buy out government, establishing their own profit and rules.

Towards the mid 19th century, however, President Juárez established the "rurales" or mounted rural police to crack down on gangs and enforce national law across Mexico. It was these rurales that helped to establish the charro look as one of manhood, strength, and nationhood.[6] Charros were quickly seen as national heroes as Mexican politicians in the late 19th century pushed for the romanticized charro lifestyle and image as an attempt to unite the nation over this legendary figure.

During World War II an army of 150,000 charros was created, the "Legión de Guerrilleros Mexicanos", in anticipation of an eventual attack of German forces. Antolin Jimenez Gamas, president of the National Association of Charros, a former soldier of Pancho Villa during the Mexican Revolution who climbed the ranks to Lieutenant Colonel in the Personal Guard of Villa's Dorados.

Early twentieth-century usage

.jpg)

_(54).jpg)

Prior to the Mexican Revolution of 1910, the distinctive charro suit, with its sombrero, heavily embroidered jacket and tightly cut trousers, was widely worn by men of the affluent upper classes on social occasions, especially when on horseback.[7] A light grey version with silver embroidery served as the uniform of the rurales (mounted rural police).[8]

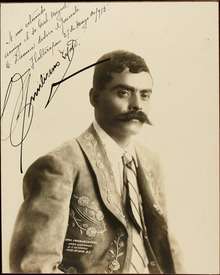

However, the most notable example of 'charrería' is General Emiliano Zapata who was known before the revolution as a skilled rider and horse tamer.

Although it is said that charros came from the states of Jalisco and the Mexico, it was not until the 1930s that charrería became a rules sport, as rural people began moving towards the cities. During this time, paintings of charros also became popular.

Use of term

The traditional Mexican charro is known for colorful clothing and participating in coleadero y charreada, a specific type of Mexican rodeo. The charreada is the national sport in Mexico, and is regulated by the Federación Mexicana de Charrería.

In Spain, a charro is a native of the province of Salamanca, especially in the area of Alba de Tormes, Vitigudino, Ciudad Rodrigo and Ledesma.[9] It's likely that the Mexican charro tradition derived from Spanish horsemen who came from Salamanca and settled in Jalisco.

In Puerto Rico, charro is a generally accepted slang term to mean that someone or something is obnoxiously out of touch with social or style norms, similar to the United States usage of dork(y).

In cinema

The "charro film" was a genre of the Golden Age of Mexican cinema between 1935 and 1959, and probably played a large role in popularizing the charro, akin to what occurred with the advent of the American Western. The most notable charro stars were José Alfredo Jiménez, Pedro Infante, Jorge Negrete, Antonio Aguilar, and Tito Guizar.[10]

Modern day

In both Mexican and US states such as California, Texas, Illinois, Zacatecas, Michoacán, Durango, and Jalisco, charros participate in tournaments to show off their skill either in team competition charreada, or in individual competition such as coleadero. These events are practiced in a Lienzo charro.

Some decades ago charros in Mexico were permitted to carry guns. In conformity with current law, the charro must be fully suited and be a fully pledged member of Mexico's Federación Mexicana de Charrería.[11]

References

- REGLAMENTO GENERAL DE COMPETENCIAS

- J. Corominas, 2008, p. 172

- Diccionario de la Real Academia Española

- Nájera-Ramírez, Olga (1994). "Engendering Nationalism: Identity, Discourse, and the Mexican Charro". Anthropological Quarterly. 67 (1): 1–14. doi:10.2307/3317273. JSTOR 3317273.

- Nájera-Ramírez, Olga (1994). "Engendering Nationalism: Identity, Discourse, and the Mexican Charro". Anthropological Quarterly. 67 (1): 1–14. doi:10.2307/3317273. JSTOR 3317273.

- Castro, Rafaela (2000). Chicano Folklore: A Guide to the Folktales, Traditions, Rituals and Religious Practices of Mexican Americans. OUP USA. ISBN 9780195146394.

- pages 27-28, "The City of Mexico in the Age of Diaz", Michael Johns, ISBN 978-0-292-74048-8

- Paul J.Vanderwood, pages 54-55 "Disorder and Progress - Bandits, Police, and Mexican Development", ISBN 0-8420-2438-7

- charro in the Diccionario de la Real Academia Española.

- p. 6 Figueredo, Danilo H. Revolvers and Pistolas, Vaqueros and Caballeros: Debunking the Old West ABC-CLIO, 9 Dec 2014

- Camara de Diputados. "Ley Federal de Armas de Fuego y Explosivos (Articulo 10 Seccion VII)" (PDF). Secretaria de Gobernacion. Archived from the original (PDF) on May 14, 2015. Retrieved May 5, 2015.]

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Charros. |

- Arte en la Charerria: The Artisanship of Mexican Equestrian Culture at the National Cowboy & Western Heritage Museum, Oklahoma City

- Art of the Charrería at the Museum of the American West

- Charrería from the Handbook of Texas Online

- Charro Days from the Handbook of Texas Online

- Charreria, the symbol of Mexico

- Federación Mexicana de Charrería (Spanish)

- Nacional de Charros (Spanish)

- Official Rulebook (Spanish)

- "CHARRO USA" U.S. Radio, Magazine and Media News off Charreria (Mexican Rodeo)