Charlotte Guillard

Charlotte Guillard (died 1557) was the first woman printer of importance.[1] Guillard worked at the famous Soleil d'Or printing house from 1502 until her death.[2] Annie Parent described her as a "notability of the Rue Saint-Jacques", the street where the shop was located in Paris, France. She became one of the most important printers of the Latin Quarter area in the city of Paris.[3] As a woman, she was officially active with her own imprint during her two widowhood periods,[4] that is to say in 1519–20, and in 1537–57. While she was not the first woman printer, succeeding both Anna Rugerin of Augsburg (1484) and Anna Fabri of Stockholm (1496), she was the first woman printer with a significantly known career.

Charlotte Guillard | |

|---|---|

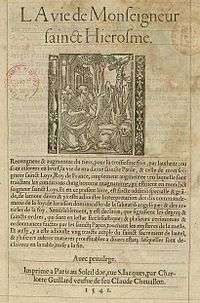

A book printed by Guillard in 1541 | |

| Born | circa 1480s likely Paris, France or province of Maine |

| Died | 1557 |

| Resting place | Paris, France |

| Nationality | French |

| Occupation | printer |

| Known for | first woman printer of note |

| Spouse(s) | 1st husband, Berthold Rembolt 1502 2nd husband, Claude Chevallon 1520 |

| Parent(s) | Jacques Guillard Guillemyne Saney |

Biography

Early life

Guillard was very likely born in the late 1480s in Paris, France. Her name is sometime spelled Guillart and in Latin books as Carola Guillard.[5] Her parents were Jacques Guillard and Guillemyne Saney. The professions of her parents are unknown, nor is recorded their social status.[1] The family's exact place of residence is not known. They had many connections with the province of Maine in France. She could very well have been born there instead of Paris. Guillard had at least three and possibly four sisters and one brother.[1]

First career

Guillard showed interest in the printing business as early as 1500 when she was still a teenager. Guillard first married Berthold Rembolt in 1502.[3] Her first husband worked with the earliest French printer Ulrich Gering.[3] Their printing business went so well that they eventually took over a small hotel that housed their family and employees.

Rembolt died in 1519. Paris businesses and crafts in the sixteenth century were regulated by the guild system. Normally women were not allowed to own a business, however they were allowed by these guilds to take over the business of their husband after their death.[1] Guillard took over management of her husband's print shop after his death. She took on the duties of proofreading the Latin publications. Her works were recognized for their beauty and accuracy. In fact she built up such a good reputation of accuracy that she was commissioned by the Bishop of Verona to publish his works. She was often associated with Guillaume des Boys, her brother-in-law.[6]

Second career

In 1520 Guillard married Claude Chevallon, a bookseller who also printed theological books. From this time forward, Guillard was known as "Madame Chevallon." She was widowed a second time in 1537.[4] Thereafter, Madame Chevallon ran his printing business on her own.[3] Her business was significant: she owned four or five printing presses with between 12 and 25 employees and a stock of 13000 books.[4] She catered to students, professional or religious clientele, often printed anti-Protestant books, and offered books in Latin as well as Greek.[4]

She probably died in 1557.[2]

More than 400 different libraries worldwide have books printed by Guillard. There are over 200 different publications by Guillard available worldwide.[3]

Selected works

- The works of the Fathers

- Jacques Toussain (Jacobus Tusanus), Lexicon Graecolatinum (1552)[7]

- Louis Lassere, La Vie de Monseigneur Sainct Hierosme (1541) (previously printed by Josse Badius ca. 1529)

- List of works printed by Charlotte Guillard (on Copac)

- Alexandri ab Alexandro iurisperiti Neapolitani genialium dierum libri sex, varia ac recondita eruditione referti (Paris: Carolam Guillard, 1539), from the Lisa Unger Baskin Collection at Duke University.

Notes

- "Charlotte Guillard, A Sixteenth Century Business Woman". Renaissance Quarterly. 36: 345–367. JSTOR 2862159.

- "SIEFAR - Dictionnaire des Femmes de l'Ancienne France". Retrieved 2010-09-28.

- "Charlotte Guillard dans la typographie parisienne". Archived from the original on 2011-07-21. Retrieved 2009-02-22.

- Béatrice Craig: Women and Business Since 1500: Invisible Presences in Europe and North America?

- "Guillard, Charlotte". Library of Congress. Retrieved 2009-11-19.

- Library of Congress

- Parisijs, Apud Carolam Guillard viduam Claudij Cheuallonij, in via Iacobæa sub sole aureo: & Guilielmum Merlin, in ponte Teloneorum sub signo hominis syluestris

Bibliography

- Beatrice Beech, "Charlotte Guillard: a sixteenth-century business woman," in: Renaissance Quarterly; No. 36, 3 (Autumn 1983:345-367)

- Rémi Jimenes, "Passeurs d'atelier . La transmission d'une librairie à Paris au XVIe siècle : le cas du Soleil d'Or", Gens du livre et gens de lettres à la Renaissance, Turnhout, Brepols, 2014, p. 309-322.

- Rémi Jimenes, Charlotte Guillard au SOleil d'Or : une carrière typographique", doctoral dissertation defended in Tours, Centre d'études supérieures de la Renaissance, 22nd of Novembre 2014 (to be published)

- Nelson, Naomi L., Lauren Reno, and Lisa Unger Baskin [eds.]. Five Hundred Years of Women's Work: The Lisa Unger Baskin Collection (New York and Durham, NC: The Grolier Club and Duke University, 2019, forthcoming via Oak Knoll Books.