Charles Todd (pioneer)

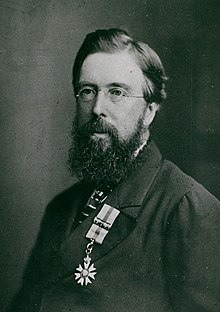

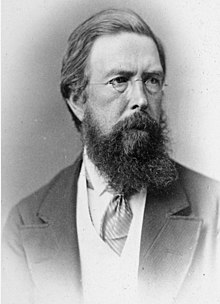

Sir Charles Todd KCMG FRS FRAS FRMS FIEE[1] (7 July 1826 – 29 January 1910) worked at the Royal Greenwich Observatory 1841–1847 and the Cambridge University observatory from 1847 to 1854. He then worked on telegraphy and undersea cables until engaged by the government of South Australia as astronomical and meteorological observer, and head of the electric telegraph department.

Sir Charles Todd KCMG FRS FRAS FRMS FIEE | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | 7 July 1826 Islington, London |

| Died | 29 January 1910 (aged 83) |

| Resting place | North Road Cemetery, Adelaide |

| Monuments | The Sir Charles Todd Observatory, the Sir Charles Todd Building |

| Nationality | Australian |

| Education | Greenwich |

| Occupation | Astronomical and meteorological observer, and head of the electric telegraph department. |

Notable work | Building the first telegraph line across Australia |

| Spouse(s) | Alice Gillam Bell |

| Children | Elizabeth, Charles, Hedley, Gwendoline, Maude, Lorna |

Early life and career

Todd was the son of grocer Griffith Todd[2] and Mary Parker;[3] he was born at Islington, London, the third of five children. Shortly after Charles's birth the family moved to Greenwich, where his father set up as a wine and tea merchant. Charles was educated and spent most of his life in Greenwich before moving to Australia.

In December 1841, he entered the service of the Royal Observatory, Greenwich, under Sir George Biddell Airy. He was fortunate that his school leaving coincided with the Astronomer Royal being granted special funding to employ an additional four young men as computers to analyse, calibrate and publish a backlog of 80 years of data. While at the Royal Observatory he was one of the earliest observers of the planet Neptune in 1846.

He was promoted to Assistant Astronomer at the Cambridge Observatory in November 1847,and officially confirmed in the position the following February. While here he used the recently built Northumberland telescope, and he was the first person to take daguerreotype photographs of the moon through it. While at Cambridge he also gained experience in using the telegraph.

In May 1854, shortly before his appointment to South Australia, he was placed in charge of the newly formed Galvanic Department at Greenwich. This was to be an extension of work he had done using the electric telegraph at Cambridge.

In February 1855, he accepted the position of Astronomical and Meteorological Observer, and Head of Electric Telegraph Department in South Australia.[4][5] [6] Meteorology was work done by astronomers; it was the recording of data so that the climate in different regions was known. The Royal Observatory was run by the Admiralty. Accurate calculation of time was an important part of the Royal Observatory's responsibilities. Greenwich Time had long been used at sea; ship's navigators relied on its accuracy to calculate their longitude.

During Todd's time at the Greenwich and Cambridge observatories the railway system was expanding, and the electric telegraph was invented. Faster railway travel, and the need for timetables and signalling systems, necessitated a change from using solar time in different regions to a standardised railway or London time (later Greenwich Mean Time). The electric telegraph made it possible to transmit information, including time, at practically instantaneous speed. So the development of the electric telegraph was driven by the requirements of the railways.

At about the time Charles Todd moved to Cambridge, George Airy arranged the connection of the Greenwich Observatory to the nearby telegraph line that was being built by the South Eastern Railway. This gave the observatories access to the electric telegraph, and the railway company access to accurate time.

Once the electric telegraph was in place, the observatory was able to control clocks and time balls at any place there was telegraphic connection. It was also possible to perform a number of astronomical and other experiments. While at Cambridge, Charles Todd was a member of a team that determined the exact degrees of longitude at Greenwich and Cambridge using the electric telegraph.

Todd's work as head of the Galvanic Department at Greenwich was to be an extension of his work using the electric telegraph. In particular, it was to transmit electric time signals to slave clocks and time balls, and to co-ordinate simultaneous astronomical or meteorological observations at multiple distant locations.

Arrival in Adelaide

Todd, along with his 19-year-old wife Alice Gillam Bell[2][7] (after whom Alice Springs is named), arrived in Adelaide on 5 November 1855. They were accompanied by Todd's assistant, 24-year-old Edward Cracknell and his wife. (Cracknell subsequently became superintendent of telegraphs in New South Wales). On his arrival Todd found that his department was a very small one without a single telegraph line.

His first commission was to erect a telegraph line between Adelaide and Port Adelaide. Such a line had been mooted some years before, and impatient with the lack of action and seeing its commercial possibilities, James Macgeorge installed one privately, cleverly avoiding obstacles put in his way by the government, and had it operating in 1855. Todd's line, more direct and technically superior (and far more expensive) was opened in February 1856, and in June of that year he recommended that a line between Adelaide and Melbourne should be constructed. Todd personally rode over much of the country through which the line would have to pass. Todd and his counterpart in Victoria proceeded to link the two colonies' telegraph systems near Mount Gambier in July 1858.[5]

Overland Telegraph Line

In 1857[8] or 1859 Todd conceived the idea of the transcontinental telegraph line from Adelaide to Darwin. Most of the country in between except for the explorations of Charles Sturt and others was unknown, and it was many years before Todd could convince the South Australian government of the practicability of the scheme.[9][10]

In January 1863 Todd addressed the Adelaide Philosophical Society about the possibility of building telegraph routes that would link to an overseas cable. In 1868 the direct line between Adelaide and Sydney was completed and was used to determine the 141st meridian, the boundary line between South Australia and Victoria. Todd's calculations showed it to be 2¼ miles farther east than had previously been determined. This led to the long-drawn-out dispute between the two colonies.

By 1870 it had been decided that the Australian Overland Telegraph Line should be constructed from Port Augusta in the south to Port Darwin in the north, though the other colonies declined to share in the cost. The southern and northern sections of the line were let by contract, and the 1000 miles in between was constructed by the department.[5][11]

The contractor at the northern end threw up his contract and Todd had to go to the north himself and finish it. Everything had to be sent by sea and then carted, but he met each difficulty as it arose, and overcame it successfully. The line was completed on 22 August 1872,[8] but the undersea cable to Darwin had broken and communication with England was not effected until 21 October. After the first messages had been exchanged over the new line, Todd was accompanied by surveyor Richard Randall Knuckey on the return journey from Central Mount Stuart to Adelaide, to be met by an enthusiastic crowd.[8]

His next great work was a line from Port Augusta, South Australia to Eucla in Western Australia – a distance of 759 miles (1,221 km) – in 1876, again surveyed by Knuckey.[8]

Postmaster General of South Australia

In 1870 the Post Office and the Telegraph Department were amalgamated, and Charles Todd was appointed Postmaster General.[12] At this time Todd was busy with the construction of the Overland Telegraph. There were problems with the running of the Post Office culminating in two robberies. Consequently, in 1874 a Government Inquiry was held into the workings of the Post Office. The outcome of the inquiry was positive; Todd was able to implement reforms that improved both the working conditions of Post Office employees and the services provided by them.

He was held in high esteem by his staff, and he continued to control his department with ability.[13]

When the colonies were federated in 1901 it was found that, in spite of its large area and sparse population, South Australia was the only one whose post and telegraphic department was carried on at a profit. Todd continued in office as deputy-postmaster-general until 1905.[5]

Meteorological work

Charles Todd was one of the pioneers of meteorology in Australasia. As the Government Meteorological Observer for the Colony of South Australia, he worked with his counterparts in the other British colonies and established the Australia-New Zealand weather observation network. His work in meteorology started with his arrival in South Australia, as he had brought with him a number of meteorological instruments that had been calibrated to instruments at Greenwich.

However, his main contribution to meteorology began with the completion of the Australian and New Zealand telegraph systems in the mid to late 1870s. Being at the centre of the network, Todd used weather observations from all the Colonies to create extensive synoptic charts. In the early 1880s Todd and his staff at the West Terrace Observatory in Adelaide were drawing inter-continental weather charts that had greater geographical reach than any other jurisdiction in the world.[14] Todd's ability to pull together the individual threads of technology, weather science, and a widely dispersed group of weather observers put him in the forefront of the profession. His chief mentor in this field was James Glaisher, one of the founders of the science of meteorology.

Todd is believed to be one of the first meteorologists to suggest that local climate was affected by global phenomena. Todd noted that abnormally high atmospheric pressure in India was matched with similar extremes in Australia, typically resulting in parallel droughts thousands of kilometres apart. This particular phenomenon is now recognised as part of the Southern Oscillation which in turn is part of the El Niño-Southern Oscillation (ENSO). These globally linked meteorological phenomena are termed teleconnections and Todd was one of the first to recognise their effect.[15]

One of Todd's legacies is the 63-volume Weather Folio collection covering the period 1879–1909. These volumes have been digitally imaged by volunteers of the Australian Meteorological Society in conjunction with the South Australian Regional Office of the Australian Bureau of Meteorology. Atmospheric pressure data from these journals has been digitised and sent to the NOAA for inclusion in the International Surface Pressure Databank as part of the ACRE project.

Government Electrician

Charles Todd had many responsibilities, but during his lifetime he referred to himself as "Government Electrician". He promoted the use of electric light in the colony by giving demonstrations of the electric arc lamp, the first in 1860. In 1867 he demonstrated the arc lamp in King William St, lighting up from the Town Hall to North Terrace (about 500m). He was instrumental in having electric lighting installed at the 1887 Adelaide Jubilee International Exhibition, the first in Australia to do so.[16]

Also in 1887, the South Australian Electrical Society was established with Charles Todd as president. He was influential in setting up the first electrical engineering course in SA.

Todd was appointed to a commission to add electric lighting to Parliament House in 1890; he supervised the installation the following year. Two years later the GPO finally had electric light.[16]

In 1899 Todd, with his son-in-law William Henry Bragg, demonstrated a wireless system that could be used over a distance of 4 km; but at this time was too expensive to be put into practice.

Finally, Todd was responsible for drawing up the draft document which would regulate electricity supply in the newly federated Australian states.[16]

Astronomical work

Though so much of his time was taken up by the duties of the postal department, Todd did not neglect his work as government astronomer.[12] Using the Adelaide Observatory (completed in 1860), which was thoroughly equipped with astronomical and meteorological instruments, he contributed valuable observations to the scientific world on the transits of Venus in 1874 and 1882, the cloudy haze over Jupiter in 1876, the parallax of Mars in 1878, and on other occasions.

He selected the site of the new observatory for Perth in 1895 and advised on the building and instruments to be obtained. He was the author of numerous papers on scientific subjects, many of which were printed in the Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society.[5]

Surveying

As "Astronomical Observer" Todd was responsible for accurate setting of the position and the time at the colony, these were part of his initial tasks on his appointment.

The precise position of the Adelaide Observatory was calculated by astronomical observations, enabling a standard point for geodetic surveys to be set.

In 1882 the South Australian Institute of Surveyors was established with Charles Todd as its inaugural president.

From 1886 until his retirement in 1905, Todd set and marked the astronomy paper that formed part of the exams for candidates aiming to become licensed surveyors. His best known work in surveying was his participation in setting the boundary line between South Australia and New South Wales that resulted in a call for a change in the existing boundary between South Australia and Victoria. This call led to a lengthy dispute between the two colonies which was finally settled in Victoria's favour.

Other achievements

The accurate determination of time was achieved by astronomical observations using a transit telescope. The Adelaide Post Office clock was installed in 1875 and it became a key timekeeper for Adelaide.[17]

In his official report to Parliament in 1862 Todd pressed the Government for a time ball to be installed near the port. An accurate signal would be sent by telegraph from the Adelaide Observatory to the port. Time balls were dropped daily at ports so that ship navigators could set their chronometers accurately, a small inaccuracy in a chronometer resulted in large inaccuracies in navigation.[17]

Todd and the Harbour Master made repeated requests for a time ball in the following years. Port Adelaide was visited by more ships after the completion of the Overland Telegraph, and approval by Parliament was eventually given in 1874 to build the time ball at Semaphore. It was completed in 1875, and is believed to have been designed by Todd and manufactured locally.[17]

Later career

In 1885 he attended the international telegraphic conference at Berlin, the following year Todd travelled to Great Britain, where he was made an honorary M.A. of the University of Cambridge.[18] In 1889 he was elected as a Fellow of the Royal Society, London. He was also a fellow of the Royal Astronomical Society, the Royal Meteorological Society and of the Society of Electrical Engineers.[4] Todd continued in his duties to posts and telegraphs in South Australia, until the newly federated Commonwealth of Australia took over all such services on 1 March 1901 and Todd became a federal public servant at the age of 74. He retired in December 1906, having been over 51 years in the service of the South Australian and Commonwealth governments.[5]

Death and legacy

Todd died at his summer home, Semaphore, near Adelaide, on 29 January 1910, and was buried at North Road Cemetery, Adelaide, on 31 January. The Sir Charles Todd Building at the University of South Australia, Mawson Lakes Campus is named after him.[19] The Astronomical Society of South Australia have also named the observatory that houses their 20-inch Jubilee Telescope, the Sir Charles Todd Observatory.[5] Each year the Telecommunications Society of Australia invites a prominent member of the telecommunications industry to present the Charles Todd Oration and awards a medal to the industry high achiever best embodying the pioneer spirit. He has been inducted into the Hall of Fame of the Institute of Engineers Australia.[1]

The ephemeral Todd River[20] and its tributary, the Charles River,[21] in the Northern Territory were named after Todd,, and a waterhole in the bed of the Todd River was named Alice Springs[22] for his wife, Alice, and subsequently used for the telegraph station,[23] and later the town.[24]

Family

Todd married Alice Gillam Bell (7 August 1836 – 9 August 1898) on 5 April 1855.[25] Their children were:

- Charlotte Elizabeth Todd (1856– ) married Henry Charles Squires ( – 12 December 1930) of Clement's Inn, London on 25 May 1887. They lived in Cambridge, England.

- Dr Charles Edward Todd (1858 – 23 May 1917) married Elsie Beatrice Backhouse of Sydney on 1 May 1889

- Hedley Lawrence Todd (1860 – 4 August 1907) married Jessie Scott ( –1945) on 17 August 1892. Hedley was a member of the Adelaide Stock Exchange.

- (Alice) Maude Mary Todd (1865 – 4 February 1929) married Rev. Frederick G. Masters ( – ) on 1 May 1900. Masters was rector of All Souls' (Anglican) church, St Peter's, Adelaide, then Holy Trinity Church, Balaklava and later vicar of St Luke's, Bath, Somerset, and Dean of Sion College in 1937.

- Gwendoline Todd (1869 – 29 September 1929) married the physicist William Henry Bragg on 1 June 1889. He and their elder son William Lawrence Bragg shared the Nobel Prize in Physics in 1915.[4]

- Lorna Gillam Todd (1877–1963) wrote a series of articles on her father for the Adelaide Chronicle[26]

References

- Engineers Australia South Australia. "Hall of Fame Inductees" (PDF). Engineers Australia. Retrieved 16 August 2015.

- H. P. Hollis, 'Todd, Sir Charles (1826–1910)', rev. K. T. Livingston, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, 2004

- Source Citation: Place: Islington, London, Eng; Collection: Dr. William's Library; Nonconformist Registers; Date Range: 1815 – 1832; Film Number: 815926

- Symes, G. W. (1976). "Todd, Sir Charles (1826–1910)". Australian Dictionary of Biography. Melbourne University Press. ISSN 1833-7538. Retrieved 7 October 2008 – via National Centre of Biography, Australian National University.

- Serle, Percival (1949). "Todd, Charles". Dictionary of Australian Biography. Sydney: Angus and Robertson. Retrieved 7 October 2008.

- SLSA: PRG 630/1. "Letter of appointment, Sir Charles Todd, 1826–1910". Retrieved 24 July 2013.

- The Singing Line, Alice Thompson, Doubleday 1999, ISBN 978-0-385-49059-7 Written by his wife's Great Great Granddaughter who retraced his route across Australia in the 1990s

- "Death of Mr. R. R. Knuckey". The Advertiser. LVI (17, 368). South Australia. 16 June 1914. p. 9. Retrieved 19 July 2019 – via National Library of Australia.

- Todd's proposal of routes and estimated costs of building segments of the telegraph line in Australia's far north held by State Records of South Australia GRG 154/5 Rough notes by Charles Todd outlining a plan for construction of the Overland Telegraph Line to Port Darwin

- Outgoing letter books and a notebook of Charles Todd as Post Master General and Superintendent of Telegraphs during the construction of the Overland Telegraph Line in 1872 are held by State Records of South Australia GRG 154/19, GRG 154/16, GRG 154/23, and GRG 154/15

- A diary kept by Todd while he was Superintendent of Telegraphs and supervising the construction of the Overland Telegraph Line is held by State Records of South Australia, GRG 154/4

- Outgoing letter books from Charles Todd as South Australian Government Astronomer (Astronomical Observer), Superintendent of Telegraphs and, later, Post Master General, 1866 – 1880, are held by State Records of South Australia, GRG 154/26

- Walker, Martin (June 2013). "Charles Todd- Postmaster General of South Australia". Philately from Australia. LXV (2–3): 49–53.

- "Sir Charles Todd". Australian Meteorological Assn. Archived from the original on 1 September 2013. Retrieved 23 July 2013.

- "El Nino – Of Droughts and Flooding Rain". Dr Neville Nicholls. Australian Broadcasting Corporation. Retrieved 21 August 2015.

- "Sir Charles Todd- Electrical Engineering". Sir Charles Todd an Australian Science and Technology Pioneer. Sir Charles Todd Research Group. Retrieved 16 August 2015.

- Abell, Lesley; Kinns, Roger (2010). "'Telegraph' Todd and the Semaphore Time Ball". Journal of the Historical Society of South Australia (38): 42–57.

- "STOCK REPORT - MR. TODD AT CAMBRIDGE". South Australian Register. Adelaide. 13 March 1886. p. 5. Retrieved 4 October 2018 – via National Library of Australia.

- "25th Anniversary of the Sir Charles Todd Building (SCT)". University of South Australia. 27 October 2004. Archived from the original on 26 August 2006. Retrieved 30 December 2006.

- Todd River Northern Territory Government Place Names Register Retrieved 9 June 2020.

- Charles River Northern Territory Government Place Names Register Retrieved 9 June 2020.

- Alice Springs (waterhole) Northern Territory Government Place Names Register Retrieved 9 June 2020.

- Alice Springs Telegraph Station Northern Territory Government Place Names Register Retrieved 9 June 2020.

- Alice Springs (town) Northern Territory Government Place Names Register Retrieved 9 June 2020.

- "Prominent S.A. Family". The Observer (Adelaide). LXXXVI (4, 504). South Australia. 19 October 1929. p. 51. Retrieved 22 August 2018 – via National Library of Australia.

- ""Telegraph Todd" And The Overland Line". The Chronicle. 95 (5, 372). South Australia. 4 December 1952. p. 24. Retrieved 22 August 2018 – via National Library of Australia.