Charles Roach Smith

Charles Roach Smith (20 August 1807 – 2 August 1890), FSA, was an English antiquarian and amateur archaeologist who was elected a fellow of the Society of Antiquaries of London, and the London Numismatic Society. He was a founding member of the British Archaeological Association.[1] Roach Smith pioneered the statistical study of Roman coin hoards.

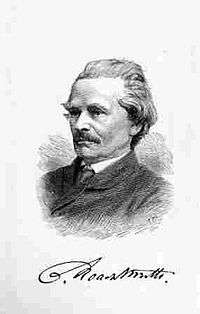

Charles Roach Smith | |

|---|---|

Portrait and signature of Charles Roach Smith | |

| Born | 20 August 1807 Shanklin, Isle of Wight, England |

| Died | 2 August 1890 (aged 82) Temple Place, Strood, Kent, England |

| Citizenship | United Kingdom |

| Known for | Museum of London Antiquities |

| Scientific career | |

| Fields | Antiquarian |

Early years

Roach Smith was born at Landguard Manor, Shanklin, Isle of Wight, the youngest of ten children of John Smith, a farmer, who married Ann, daughter of Henry Roach of Arreton Manor. His sisters included Anne Eveleight, Mary Holliffe, and Maria Smith.[2] Their father died when Roach Smith was young, and his maternal grandfather's house, Arreton, became his second home. The mother died about 1824. Roach Smith went to the school of a Mr. Crouch at Swaythling, and when the master migrated to St Cross, near Winchester, Roach Smith followed him. About 1820, he went to the larger school of Mr. Withers at Lymington.

Career

In 1821, Roach Smith was placed in the office of Francis Worsley, a solicitor at Newport, but soon tired of this occupation. The army was then suggested for him, but in February 1822 he was apprenticed to a Mr. Follett,a chemist at Chichester. After remaining there for about six years, he went to the firm of Wilson, Ashmore, & Co., chemists at Snow Hill, London. He established his own business as a chemist in 1834, having set himself up at the corner of Founders' Court, Lothbury. When his premises were taken over by the city, he suffered a great loss to him. He removed to Finsbury Circus, where he lived from 1840 to 1860.

At a very early date in his life Roach Smith felt the passion of collecting Roman and British remains, and he was encouraged by Alfred John Kempe, whom he considered to be his "antiquarian godfather". For twenty years, during London excavations or dredging of the River Thames, he was on the alert for antiquities and found several. The knowledge of his acquisitions spread when he published in 1854 a Catalogue of the Museum of London Antiquities. The antiquities catalogued in this publication were collected during extensive street and sewage improvements in the city of London, as well as work on the Thames near the London Bridge, the collection being formed under accidental circumstances. His collection contained a portion of the antiquities found in London, becoming a self-imposed stewardship, and resulting in the formation of his Museum of London Antiquities.[3] His fellow antiquaries urged that the collection should be secured by England, but his offer of it to the British Museum in March 1855 was declined as they could not agree on a price. Later, they were transferred to the British Museum and formed the nucleus of the national collection of Romano-British antiquities.[4]

Roach Smith was by this time accepted as the leading authority on Roman London. He subsequently pioneered 'urban site observation' and his Illustrations of Roman London (1859) remained the principal work on the subject until 1909. He wrote the book for the most part as a result of his personal investigations while he lived in Lothbury and in Liverpool Street, in the City of London.[5]

Learned societies

Roach Smith belonged to many learned societies at home and abroad. He was elected Fellow to the Society of Antiquaries of London in 1836. For many years, he compiled the monthly article of "Antiquarian Notes" in The Gentleman's Magazine. He was a writer for the Athenaeum of the Society of Antiquaries of Newcastle upon Tyne (of which he was a member), and in the Transactions of several other antiquarian bodies. When, through the medium of his friend, the Abbé Cochet, he intervened successfully with Napoleon III for the preservation of the Roman walls of Dax, a medal was struck in France in 1858 in honour of Roach Smith to commemorate the event. At a meeting in 1890 of the Society of Antiquaries, it had been proposed to strike a medal in his honour, and to present him with the balance of any fund that might be collected. The medal, in silver, was presented to him on 30 July, three days before his death, and there remained for him the sum of one hundred guineas. A marble medallion by G. Fontana belongs to the Society of Antiquaries. He was a Fellow of the Royal Society of Antiquaries of the North; and a member of the Societies of Antiquaries of France, of Normandy, of Picardy, of the West, and of the Morini.[3]

For more than fifty years, Roach Smith took a keen interest in the work of the London Numismatic Society. From 1841 to 1844, he was one of its honorary secretaries, and from 1852 he was an honorary member. He was the first presenter of the Liudhard medalet to the Numismatic Society in 1844.[6] He made a variety of contributions to the Numismatic Chronicle, and in 1883 he received the first medal of the society, in recognition of his services in promoting the knowledge of Romano-British coins.

In conjunction with Thomas Wright, he founded the British Archaeological Association in 1843, and he frequently wrote in its journal. In 1855 he was a founder member of the London and Middlesex Archaeological Society. After his retirement to Strood, he actively assisted in the work of the Kent Archaeological Society, and contributed many papers to the Archaeologia Cantiana. Much of his earliest work was contributed to the Archaeologia. He was also an honorary member of the Archaeological Societies of Madrid, Wiesbaden, Mayence, Treyes, Chester, Cheshire and Lancashire, Suffolk, and Surrey. Roach Smith was an honorary member of the Royal Society of Literature, the Society of Antiquaries of Scotland, and the Société d'émulation d'Abbeville.[3] Although most recognised for his work on Roman London, his archaeological influence went much further than London and inspired the forming of many local archaeological societies across the country, therefore making archaeology much more accessible to the wider society.[7]

The Shadwell forgeries

In 1857, a steady stream of lead, medieval artifacts began circulating in London. Their source was two Londoners, William Smith and Charles Eaton, illiterate mudlarks, who purportedly obtained them from the large-scale excavations then taking place at Shadwell Dock. However, in April 1858 the items were denounced as forgeries in a lecture to the British Archaeological Association by Henry Syer Cuming.[8]

The lecture was reported by the Athenaeum magazine. This resulted in a suit for libel from a London antique dealer who, although not named in the magazine report, claimed he had been implicitly libeled as he was the only seller of them. The trial was widely reported; Roach Smith appeared as a witness for the plaintiff, and asserted in his testimony the items were a previously unknown class of object with an unknown purpose. However, he was confident of their age. Several other antiquarians gave similar testimony.[8][9]

In 1861, Roach Smith published volume five of his work Collectanea antiqua. This included an article stating the items were crude, religious tokens, dating from the reign of Mary I of England, that had been imported from continental Europe as replacements for the devotional items destroyed during the English Reformation.[10] However, later the same year, the businessman, politician and antiquarian Charles Reed conclusively proved they were fakes by obtaining evidence that William Smith and Charles Eaton, had been manufacturing the items all along.,[11]

Later years

After his business dwindled, he purchased, as a place of retirement, the small property of Temple Place, on Cuxton Road, Strood, Kent, and some adjoining horticultural land. In 1864, he was involved in an action at law with the dean and chapter of Rochester over some reclaimed land adjoining his property, and Roach Smith won the case. The garden at Temple Place was in later life his chief recreation, and he enjoyed cultivation of its grounds. He especially applied himself to pomology as well as growing vines in open ground, making considerable quantities of wine from the grapes which he reared. His pamphlet On the Scarcity of Home-grown Fruits in Great Britain, which first appeared in the Proceedings of the Historical Society of Lancashire and Cheshire in 1863, passed into a second edition, and a thousand copies were distributed in France and Germany. He advocated the planting of the waste ground on the sides of railways with dwarf apple trees and with other kinds of fruit, and this suggestion was adopted to a considerable extent abroad and to a limited degree in England.

Roach Smith was unmarried, and a sister kept house for him at Temple Place. She died in 1874, and was buried in Frindsbury churchyard. After a confinement to his bed for six days, he died on 2 August 1890, and was buried in the same churchyard.

Works

- (1839), List of Roman Coins found near Strood

- (1848), Collectanea antiqua : etchings and notices of ancient remains, illustrative habits, customs, and history of past ages

- (1850), The Antiquities of Richborough, Reculver, and Lymne

- Smith, Charles Roach (1852). "Anglo-Saxon and Frankish Remains". Collectanea Antiqua. II: 203–248. Retrieved 17 September 2017.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- (1856), Inventorium sepulchrale : an account of some antiquities dug up at Gilton, Kingston, Sibertsworld, Barfriston, Beakesbourne, Chartham, and Crundale, in the County of Kent, from a.d. 1757 to a.d. 1773

- (1859), Illustrations of Roman London

- (1860), On the Importance of Public Museums for Historical Collections

- (1863), Retrospections: social and archaeological

- (1870), The Rural Life of Shakespeare, as illustrated by his works

- (1871), A Catalogue of Anglo-Saxon and other Antiquities discovered at Faversham, in Kent, and bequeathed by William Gibbs of that town to the South Kensington Museum

- (1877), Remarks on Shakespeare: his birthplace, etc.: suggested by a visit to Stratford-on-Avon in the autumn of 1868

- (1878-1880), Collectanea Antiqua, Etchings and Notices of Ancient Remains, illustrative of the Habits, Customs and History of Past Ages, vol 7.

- (1879), Address to Strood Institute Elocution Class

- (1883), Retrospections, Social and Archaeological, Vol 1.

- (1886), Retrospections, Social and Archaeological, Vol 2.

- (1891), Retrospections, Social and Archaeological, Vol.3.

References

- Michael Rhodes, 'Smith, Charles Roach (1806–1890)', Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, 2004 accessed 12 May 2007

- Roach Smith, Charles (1848). Collectanea antiqua: etchings and notices of ancient remains, illustrative of the habits, customs, and history of past ages (Now in the public domain. ed.). J. R. Smith. pp. Dedication Page. Retrieved 27 July 2011.

- Roach Smith, Charles (1854). Catalogue of the Museum of London Antiquities (Now in the public domain. ed.). The Richards. pp. Front Cover, iii, iv, v. Retrieved 27 July 2011.

- British Museum Collection

- Roach Smith, Charles (1859). Illustrations of Roman London (Now in the public domin. ed.). Printed for subscribers, and not published. p. i. Retrieved 27 July 2011.

- Grierson, Philip (1979). "The Canterbury (St. Martin's) Hoard of Frankish and Anglo-Saxon Coin-Ornaments". Dark Age Numismatics: Selected Studies. London: Variorum Reprints. pp. 38–51, Corregida 5. ISBN 0-86078-041-4.

- Scott, S. (2017). "'Gratefully dedicated to the subscribers': The archaeological publishing projects and achievements of Charles Roach Smith". Internet Archaeology (46). doi:10.11141/ia.45.6.

- Halliday, Robert (1986). "The Billy and Charley Forgeries" (PDF). London Archaeologist. 5 (9): 243–7.

- "Home Circuit". The Times (23065). London. 6 August 1858. p. 12.

- Roach Smith, Charles (1861). Collectanea antiqua : etchings and notices of ancient remains, illustrative of the habits, customs, and history of past ages. 5. London : J.R. Smith. pp. 252–260. OCLC 162748195.

- "Shadwell Dock Forgeries". Collections Online. The British Museum. Retrieved 11 January 2016.

External links