Charles Frodsham

Charles Frodsham (15 April 1810 – 11 January 1871)[1] was a distinguished English horologist, establishing the firm of Charles Frodsham & Co, which remains in existence as the longest continuously trading firm of chronometer manufacturers in the world. In January 2018, the firm launched a new chronometer wristwatch, after sixteen years in development. It is the first watch to use the George Daniels double-impulse escapement.[2]

Charles Frodsham | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | 15 April 1810 London, England |

| Died | 11 January 1871 (aged 60) Bloomsbury, London, England |

| Nationality | British |

| Education | Bluecoat School |

| Awards | Telford Gold Medal (1847) |

| Scientific career | |

| Fields | Clock, Watch & Chronometer Maker |

| Institutions | Fellow of the Royal Astronomical Society Vice President British Horological Institute |

Early history

Frodsham was educated at the Bluecoat School, Newgate,[3] London and then apprenticed to his father William James Frodsham FRS, a respected chronometer maker and co-founder of Parkinson & Frodsham. Charles showed early promise with two chronometers submitted to the 1830 Premium Trials at Greenwich, one of which was awarded 2nd prize. Nine further chronometers by Charles were entered to the Premium trials until they ceased in 1836.[4]

Established in business

Soon after marrying Elizabeth Mill (1813–1879), Frodsham founded his own business at No. 7 Finsbury Pavement.[5] He rapidly established himself as a leading London chronometer maker. With the death of another major chronometer maker, John Roger Arnold (son of the eminent John Arnold), Charles acquired the Arnold business in 1843, moving his family and business address to 84 Strand, London.[6] Trading as ‘Arnold & Frodsham, Chronometer Makers’ continued till 1858.

Technical brilliance

Charles Frodsham was a prolific and highly regarded horological writer, publishing numerous articles on the discipline. He corresponded with George Biddell Airy, Astronomer Royal, over many years, much of which correspondence is preserved at Cambridge University Library,[7] covering topics such as middle temperature error, quick trains as advocated by Thomas Earnshaw, Greenwich Mean Time and Airy’s remontoire. In 1871, Frodsham published The History of the Marine Chronometer, the first English language treatment of the subject.[8]

Exhibitions, awards & medals

Frodsham was awarded the Telford Gold Medal from the Institution of Civil Engineers for his 1847 lecture on the laws of isochronism. At the Great Exhibition in 1851, he was awarded a first-class medal for his timekeepers. The firm won fourteen further medals and honours at the major international exhibitions over the rest of the nineteenth century. At the 1862 International Exhibition, Frodsham not only exhibited but was also one of the jurors, writing the detailed horological section report.[9]

Successor to Vulliamy

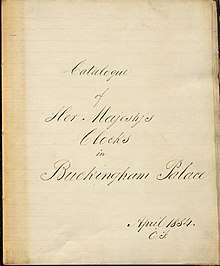

On the death of Benjamin Lewis Vulliamy (1780–1854), Frodsham purchased the goodwill of the Vulliamy business, and on the recommendation of Airy succeeded Vulliamy as ‘Superintendent and Keeper of Her Majesty’s Clocks at Buckingham Palace’,[10] cementing the firm’s position as leading international clockmakers.

Horological societies

Frodsham was a founding member, and later Vice President, of the British Horological Institute, and a Liveryman of the Worshipful Company of Clockmakers, in which he served as Master in 1855 and 1862.[11]

Legacy and succession

Frodsham died of liver disease in 1871, and was buried at Highgate Cemetery, London. His obituary stated that ‘during a long and honourable career, he distinguished himself by his devotion to the science of horology, which he greatly advanced, and his clever works upon the subject are regarded as authoritative by members of the trade.’[12]

Charles’ son Harrison Mill Frodsham (1849–1922) took over the firm, following in his father’s footsteps by publishing his own theoretical horological material, including an important series of articles entitled ‘Some materials for a Resume of Remontoires’.[13]

The firm continued to supply marine chronometers to the Greenwich trials, achieving significant success. Between 1831 and 1920, the Admiralty purchased sixty Charles Frodsham marine chronometers, and a number of pocket chronometers and deck watches, most notably a watch used by Ruth Belville, the Greenwich Time Lady, now in the Lord Harris collection at Belmont. [14]

Precision timekeeping

In the 2nd half of the nineteenth century, the firm provided sidereal regulators for new observatories being established worldwide, notably in Australia at Sydney and Melbourne; in Italy at Padua, Palermo and Naples; and in the USA at Harvard and Lick.

In addition to the production of standard high-grade pocket watches and domestic clocks, the firm specialised in complicated timepieces, including Tourbillon and Karrusel watches, many of which were submitted for observatory testing, frequently scoring highly. Charles Frodsham tourbillon No. 09182 (now in the Lord Harris collection at Belmont) ,[15] with marks of 93.9, holds the record for the highest score ever achieved by an English watch tested at the Kew Observatory. Such watches were inscribed with the letters AD. Fmsz. This cryptogram for the year Anno Domini 1850 is formed by the numerical sequence of the letters in ‘Frodsham’, with the addition of Z for zero, and was used from that date on by the firm to indicate first quality.

Corporate history

From 1884 the firm traded as Charles Frodsham & Co., becoming incorporated in 1893, and moving to new premises at 115 New Bond Street in 1895. A new branch specializing in motor accessories was opened in nearby Dering Street in 1911, to sell speedometers and car clocks. The main business moved again in 1914 to 27 South Molton Street, London, where it remained until considerable damage caused by an air raid in 1941 forced a move to 62 Beauchamp Place.

From the late 1940s through to the 1970s, the firm resided at 173 Brompton Road, where it concentrated on the production of mantel and carriage clocks. In 1997 the company moved to new retail premises at 32 Bury Street, St. James’s, and set up a manufacturing and conservation workshop in East Sussex, where it continues today, specialising in English precision horology.[16]

References

- Birth: Vaudrey Mercer, The Frodshams (AHS: Ticehurst, 1981), p. 76; death: obituary in Clerkenwell News & London Daily Chronicle (18 January 1871)

- "Charles Frodsham Introduces the Long Awaited Double Impulse Chronometer Wristwatch". SJX website.

- Mercer, Frodshams, p. 76

- "The Royal Observatory Greenwich - where east meets west: Rates of chronometers and watches on trial at the Observatory, 1766-1915". www.royalobservatorygreenwich.org. Retrieved 2017-10-18.

- The Post Office London Directory (1841), page 397

- Gould, Rupert (1923). The Marine Chronometer - Its History and Development. London: J.D. Potter. p. 115.

- "Airy, Sir George Biddell (1801-1892) Knight, astronomer and mathematician".

- Charles Frodsham, The History of the Marine Chronometer (William Clowes and Sons, Stamford Street and Charing Cross, 1871).

- Illustrated Catalogue of the International Exhibition 1862, British Division Vol. III, Class XV, Horological Instruments, Jurors reports, pp. 1-21

- Charles Frodsham & Co. Museum Archive

- "Masters since 1631".

- "Obituary". Clerkenwell News & London Daily Chronicle. 18 January 1871. Retrieved 18 October 2017.

- Harrison M. Frodsham, 'Some Materials for a Resume of Remontoires', Horological Journal, Vol. 20 (1877-78), 21-23; 49-53; 66-67; 76-79; 86-88; 104-105; 120-122; 130-131; 163-165. Vol.21 (1878-79), 58-59; 75

- "Clocks at Belmont".

- "Clocks at Belmont".

- "Charles Frodsham".